Any ethnography stands or falls on its methodological approach. While Juan Thomas Ordóñez’s fascinating Jornalero: Being a Day Laborer in the USA promises a detailed look into the challenging lives of migrant Latin American day workers, its lacklustre methodology hamstrings its intriguing findings.

Ordóñez is aware of some of these methodological problems, but apparently blind to others. Early on, he bluntly states that undocumented day labourers in Berkeley may be atypical because of the uniqueness of the community’s liberal politics and history, but nevertheless he then chooses to follow a small group of these very men for two years. It seems, according to his account, that one major reason for his decision to study these Berkeley workers is that they gather just blocks from his apartment.

But what about the thousands of other jornaleros, some of whom are in nearby Oakland, San Francisco and Richmond? The author could have strengthened his methodological approach by studying these men – he clearly has the time to conduct the research – but chooses instead to stick to his one small group. In fact he seems oblivious to other methodological choices, including the weak internal and external validity of his specific findings. And even though the number of jornaleros he studies is small, there is no demographic profile describing such fundamentals as their age, nation of origin, family size, years working as a jornalero or estimated income.

Thus despite the author’s time-consuming ethnography, the internal and external validity of the data remain in question owing to his methodological decisions. To his credit, Ordóñez chooses to spend two years observing these men waiting patiently on designated sidewalks for work; he also engages in lengthy conversations with them. From this very detailed, frequently intriguing information he describes the system of day labour in Berkeley from the labourers’ perspective, focusing on the multiple ways these men are forced to navigate a community that marginalises them in every way possible, and must live in fear of the governmental bureaucracies surrounding them, including the Border Patrol.

Ordóñez is particularly skilled at describing the personal strengths and weaknesses of each of the men he befriends, emphasising how over time their daily challenges shape and change them. But while we are presented with impressive insights through these narratives, we are also asked to take their countless stories at face value, stories that the researcher acknowledges can be cultural exaggerations and/or attempts at face-saving.

For whatever reason, Ordóñez observes these men only on the street, occasionally meeting them at their homes or for a drink after work. He almost never follows them to their work sites where he might observe their actual behaviour, the nature of their work and the expectations of their employers, including their reported unwillingness to pay a fair wage. Nor does he interview any of these employers, or the social workers and others who know about some aspects of the lives of jornaleros.

In the end what we have is a case study of a small number of jornaleros in one atypical California city, based upon these workers’ own detailed telling of their lives. Lacking internal and external validity, this book is merely an exploratory study that points to a variety of intriguing themes, rather than a significant contribution to a very timely topic.

Robert Lee Maril is professor of sociology, East Carolina University.

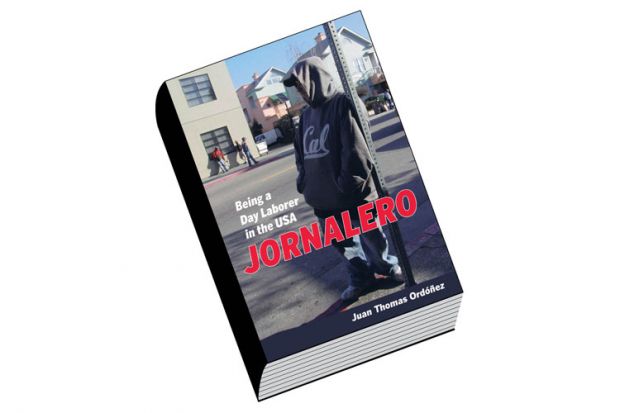

Jornalero: Being a Day Laborer in the USA

By Juan Thomas Ordóñez

University of California Press, 280pp, £44.95, £19.95

ISBN 9780520277854, 7861 and 9780520959965 (e-book)

Published 30 June 2015