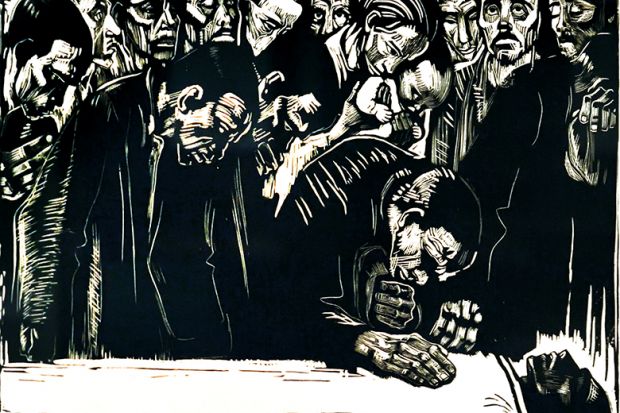

What can the amount of buckling by a back express about the world of its bearer? How might oversized hands, merged with the woodgrain into which they are cut, articulate depression, economic and social? How do creamy white scratches in solid expanses of black ink, reworked with white gouache, highlight widespread misery? Can solid blocks of darkness, variegated densities of inks, frantic scratches in bodies, cross-hatching, closed or open lines, convert to emblems of interwar suffering, wrought, and wrought again, through the mechanisms of printing?

The images in Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics, based on an exhibition of lithographs, woodcuts, etchings and crayon drawings that continues at the Getty Center in Los Angeles until 29 March, are drawn from the collection of Dr Richard A. Simms. This collector focused on acquiring works in various iterations, including preparatory drawings, working proofs, trial prints, differently generated prints of the same subject. On show are multiple versions of themes as they move across media, seeking the appropriate form to express the mood, the affect, strained between desolation and struggle. Laid out in this book, which includes insightful commentary by a selection of scholars brought together by print curator Louis Marchesano, are processes of decision-making, refinement, augmentation, resulting in an outlining of procedures that are rarely visible.

Many books have reproduced and analysed the oeuvre of Käthe Kollwitz since she garnered critical attention in the late 19th century with a series of etchings of weavers, based on an 1844 uprising of Silesian workers. Her work has been categorised as a gloomy and emotive protest against dispossession, poverty, war and state brutality. Mothers cradle dead children, victims of scarcities, and, later, as Kollwitz herself was to experience, their sons’ sacrifices in war. One etching from around 1900 is titled The Downtrodden, with parents despondently confronting their dying daughter. Twenty years later, Kollwitz produced a memorial image for the communist leader Karl Liebknecht, cut down at the behest of the state, a corpse, surrounded by broad-browed men bent in mourning.

The critical literature over the years, in the democratic-capitalist West and in the communist bloc East, has tussled over whether these images are an expression of pity and impotence, to be remedied, if at all, only by conscience-checking on the part of the wealthy, or whether they represent an agitational praxis to stir the proletariat into revolutionary action, in order to right the wrongs forcefully. This book reflects on the history of those debates, exposing some of their contours.

There is, for example, an insightful discussion of what it meant for Kollwitz and her critics to engage in Tendenzkunst, or “Art with a Purpose”. Karl Schleffler, whose book on women and art, in 1908, declared that the former had no business engaging with the latter, condemned her “posterlike” work for its inability to transcend sentiment to become art. The Bolshevik Anatoly Lunacharski praised that very same “posterlikeness” for its graphic vividness. The resolution here is to point out the subtleties within what may be “posterlike”, its, or her, attention to detail, or details, her responsiveness to the specificities of each image in its dialogue with the world and the expressive needs of its victims, which is what for Kollwitz counted as “artistic quality”.

Esther Leslie is professor of political aesthetics at Birkbeck, University of London.

Käthe Kollwitz: Prints, Process, Politics

Edited by Louis Marchesano

Getty, 196pp, £30.00

ISBN 9781606066157

Published 9 January 2020

后记

Print headline: Black and white trails of tears