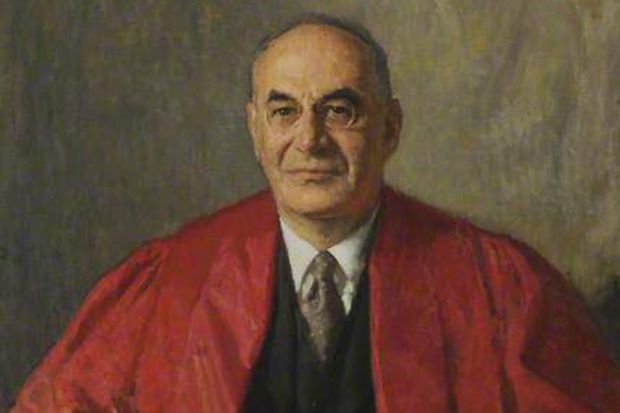

Recently, while helping to clear out my grandparents’ house, I came across a copy of a lecture that my great-grandfather gave in 1952. At the time, he had just been appointed master of University College, Oxford, becoming the first American in history to be head of an Oxford college.

The title of the lecture – “The Nature and Purpose of a University” – was what caught my eye. A lot of column inches have been devoted to the supposed existential crisis of higher education in Britain and the US over the past year. Brendan O’Neill’s article (originally published in November 2014) castigating today’s undergraduates for valuing the “right to be comfortable” more highly than free speech was one of The Spectator’s most-read pieces of 2015.

In September, The Atlantic ran a cover piece – “The Coddling of the American Mind” – making a very similar point. The rise of so-called microaggressions (“small actions or word choices that seem on their face to have no malicious intent but that are thought of as a kind of violence nonetheless”) and trigger warnings (“alerts that professors are expected to issue if something in a course might cause a strong emotional response”) is taken as a sign that higher education is headed towards hell in a handcart.

The furore over the statue of Cecil Rhodes – noted racist and philanthropist – at Oriel College (incidentally, just round the corner from University College, where my great-grandpa’s own philanthropy is commemorated by a plaque on the wall of a building that bears his name) is just the latest episode in this saga.

Read more: Student activists hit back at Oxford chancellor in Rhodes debate

So what does the class of 1952 have to say to the class of 2016? The thing that struck me most was how little the essence of the debate has moved on.

The world my great-grandfather inhabited feels very remote today. In 1952, there were about 75,000 students enrolled at university – roughly 2 per cent of the college-age population; today, it’s more than 2 million – closer to 50 per cent. And yet, even then, there were concerns that “if the number of university graduates is increased then they will find difficulty in obtaining employment”. It’s a concern that my great-grandfather dismissed, saying: “there is no field in which the university man [sic] ought not to take a leading part if he is adequately trained”.

Intriguingly, at that time, this scarcely applied to his own field: law. In the early 1950s, less than 10 per cent of solicitors went to university, let alone read law. Banks showed little interest in employing graduates and if you’d suggested to an Oxford graduate in 1952 that they might like to consider a career in management consulting, the response would almost certainly have been utter bafflement.

In other ways, too, things have changed. In 1952, one-fifth of all students in the UK were at either Oxford or Cambridge, where they would have been required to pass tests in Latin and Greek in order to be admitted to the university, irrespective of what subject they were there to study. Until just two years previously, there had been 12 MPs in the House of Commons representing university seats, and graduates received two votes – one in their home constituency and one in their university constituency.

Yet, despite the foreignness of context, the content is familiar. Some of the language is dated, but the ideas are the same ones being trumpeted today by those who are worried that universities have lost their way:

“The purpose of a university in teaching is…to develop the complete man in the sense in which this phrase was used by the Greek philosophers. The complete man is not the man who has the most knowledge, but he is the one who is best equipped to acquire it.”

And this was by no means new thinking in 1952 either. He goes on to quote Cardinal Newman, writing a century earlier:

“A habit of mind is formed, which lasts through life, of which the attributes are, freedom, equitableness, calmness, moderation, and wisdom; or what I have ventured to call a philosophical habit. This then I would assign as the special fruit of the education furnished at a university.”

He goes on to find several other ways of making much the same point. There are only two qualities a university ought to impart, he argues: “the first is clarity and honesty of thought, and the second is intellectual curiosity”.

Furthermore, “the highest form of education consists in encouraging a man to ask questions”. (I think you’ve probably got a pretty good sense of my great-grandfather’s rhetorical style by now. He seems to come from the “keep bludgeoning them over the head with the same message until it begins to seep through their thick skulls” school of public speaking. It must run in the family.)

But he saves the best until last. In his final recapitulation of this central theme, he pulls out a wonderful quotation. The original progenitor of this idea is, supposedly, the 18th-century German philosopher Gotthold Lessing, but my great-grandfather actually gets it second-hand from Lord Haldane, a Liberal (later Labour) politician and lawyer who was at the peak of his influence in the first quarter of the 20th century:

“It was Lessing who declared that were God to offer him the Truth in one hand and the Search for Truth in the other, he would choose the Search.”

What could be more apt in the age of Donald Trump and #RhodesMustFall – a world caught between the extremes of Islamic State terrorists who revel in their own barbarism and hard-line anti-immigration activists, who would rather see desperate refugees drown than share their street. (Before you say anything, I am not, repeat not, suggesting any kind of moral equivalency between these various examples.)

In an uncertain world, certainties, including false ones, seem to have a special allure. If universities could immunise us against certainty of mind, then truly they would be delivering an immeasurable benefit to the cause of democracy and humanity.

Richard Roberts is a freelance writer. This is an edited version of a post that originally appeared on his blog, Musings of a Young Londoner.