Why are pears shaped the way they are? Why is the stinkhorn fungus formed like a phallus? Why are wasps striped yellow and black? Why is the guillemot’s egg shaped like a pear? Why do zebras have stripes?

Evolutionary biologists are interested in understanding the way the world is and these are the types of questions that keep them awake at night. They can be answered in one of two ways. We might either be asking about the genetic mechanisms responsible for creating those colours and shapes during the organism’s development, or we might be asking about their function or purpose. The focus of this second type of question is the adaptive significance of features. Given that most traits have evolved through natural selection, our starting assumption must be that those traits matter. How, then, does having pear-shaped fruit rather than spherical fruit help pear trees produce descendants? Sometimes such questions are easily answered. Experiments show that striping on wasps enhances their survival by warning potential predators to keep clear. Wasps sting; predators keep away; wasp survives.

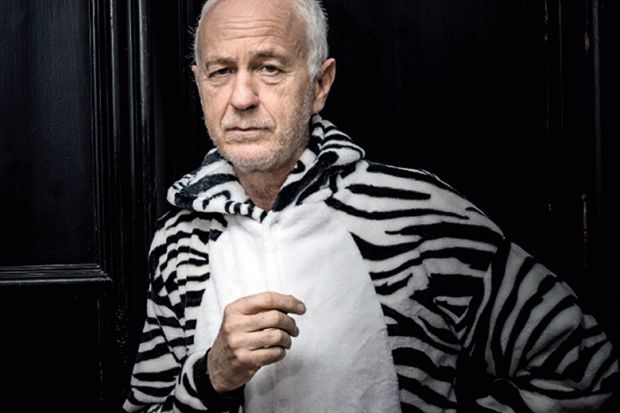

Figuring out what things are “for”, however, can be surprisingly difficult. Tim Caro has spent the past 10 years finding out why the zebra got its stripes.

Caro’s study exemplifies how one should conduct such an investigation: you (or someone else) come up with one or more ideas (hypotheses), from which you derive some predictions, and you then subject those ideas to the most rigorous tests you can devise. The best tests are experiments, but as this research shows, comparative studies can be invaluable, too.

Sounds easy, doesn’t it? In most cases, it isn’t. It has taken Caro a long time to work his way systematically, carefully and quantitatively through the 18 different hypotheses that have been suggested for why zebras have stripes.

Most people think that the zebra’s pyjama-like pelage has evolved to confuse predators such as lions and hyenas. Unlikely, it seems, on the basis of Caro’s work. Perhaps stripes help to conceal zebras from predators. Not true. Could the zebra’s stripy appearance, like that of wasps, be a warning? Those stripes converge on the mouth and zebras bite, hard. No: there’s no evidence for this either. The answer seems to be that stripes discourage biting flies. Insects such as horseflies and tsetse flies rely on a blood meal to reproduce; they bite all sorts of mammals and birds, causing irritation and discomfort, and they may also transfer diseases such as sleeping sickness. Biting flies don’t like stripes, and given a choice prefer to land on unstriped surfaces.

Said like this, it sounds very easy, but Caro and his assistants have laboured hard and long in the heat of the African sun, and in the library at the University of California, Davis, to solve this problem. This is an exemplary study. This is how science should be done: patient, systematic, careful and comprehensive. Charles Darwin referred to his work On the Origin of Species as “one long argument” for evolution by natural selection. Caro’s Zebra Stripes is one long argument also – for this is in essence a 300-page scientific paper – and as such makes a fine academic behavioural ecology monograph.

Tim Birkhead is professor of behaviour and ecology, University of Sheffield. His most recent book The Most Perfect Thing was shortlisted for the 2016 Royal Society popular science prize.

Zebra Stripes

By Tim Caro

University of Chicago Press, 320pp, £31.50

ISBN 9780226411019 and 1156 (e-book)

Published 5 December 2016

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login