Thirty-three years after his death, architect and inventor Buckminster Fuller has been rescued from relative obscurity. Jonathon Keats’ book is the most recent of several excellent tomes. Equally important in this reappraisal, however, was the exhibition Buckminster Fuller: Starting with the Universe, shown at New York’s Whitney Museum and Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art in 2008 and 2009.

Obscurity for Fuller would have seemed inconceivable in 1968, when Allan Temko published a provocative essay, “Which Guide to the Promised Land? Fuller or Mumford?” Without taking sides, Temko insightfully compared the differing visions of Fuller and his contemporary, the scholar Lewis Mumford, just when each had become a hero to younger audiences: Mumford, through his analyses of modern technology gone awry, as in Vietnam; and Fuller, courtesy of his optimistic visions of technology’s potential to transform the world and to create new communities.

Keats’ title comes from the “stern voice inside his head” that supposedly stopped Fuller, aged 32, from drowning himself in frigid Lake Michigan in winter 1927 after a series of failures had left him in despair. But the voice declared: “You do not have the right to eliminate yourself…You belong to the universe.” Fuller’s life turned around, and he began his journey as a self-described “comprehensive anticipatory design scientist”.

Following Loretta Lorance’s 2009 biography Becoming Bucky Fuller, however, Keats denies that Fuller ever contemplated suicide. Rather than putting this (imagined) incident behind him, Fuller cleverly repackaged it as a key part of an unappreciated visionary’s life. Keats also follows other scholars on Fuller’s coining of terms that, while sometimes clarifying – such as “spaceship earth” – at other times degenerated into irritating jargon, as with his “Dymaxion” house, car and bathroom.

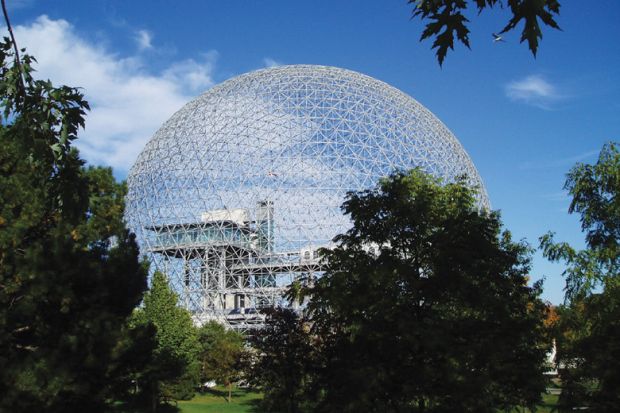

In arguing for Fuller’s ever-greater relevance, Keats rightly emphasises his role as a visionary seeking to benefit the most people in the shortest possible time while expending the fewest natural resources. Paradoxically, Fuller was as much a sensitive environmentalist as a cold-hearted technocrat. But he rarely acknowledged flaws in his designs. When his famous geodesic domes leaked and failed to handle temperature change and humidity, as they frequently did, he waved off all criticisms as merely a matter of materials. What he found harder to deal with was the lack of enthusiasm of the multitudes whom he envisioned living happily together beneath his giant domes.

As Keats appreciates, Fuller may have been the last American visionary who was not “in it for the money”. Unlike contemporary technological prophets, he provided an explicit moral critique of the world that is missing from the likes of Alvin and Heidi Toffler, John Naisbitt and Patricia Aburdene, Jeff Bezos and Eric Schmidt. A key figure in the Western utopian tradition, Fuller argued in his best-selling 1969 work Utopia or Oblivion: The Prospects for Humanity that humanity had no choice but to embrace the future or to decline. Indeed, he insisted, Utopia was possible within our own lifetimes. (Good luck with that!)

Despite never establishing any actual communities, utopian or otherwise, Fuller invented enough actual components of potential communities to qualify as a genuine communitarian. Thanks to Keats’ illuminating book, however, we can surely conclude that Fuller’s greatest invention was himself.

Howard Segal is professor of history, University of Maine. He contributed an essay, “America’s Last Genuine Utopian”, to the edited volume New Views on R. Buckminster Fuller (2009).

You Belong to the Universe: Buckminster Fuller and the Future

By Jonathon Keats

Oxford University Press, 216pp, £16.99

ISBN 9780199338238

Published 12 May 2016

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login