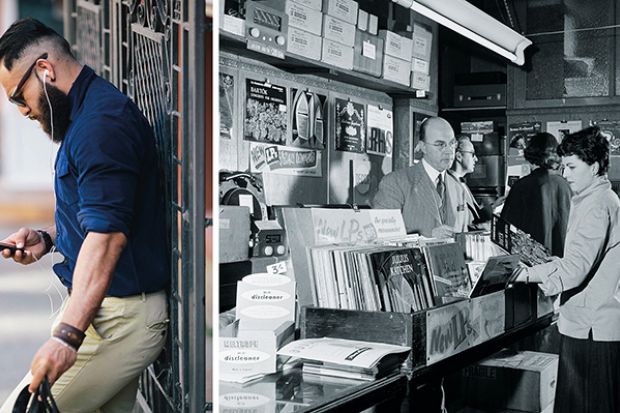

Most people are aware that the way that we own and consume music has undergone a series of shifts – from vinyl and tape to CDs, from CDs to digital files on iPods and then smartphones, and most recently from digital files to streaming services including Spotify and Apple Music. Fewer people may be aware that this is just one aspect of a much bigger set of shifts – and even fewer of the deeper impact of these shifts. In The End of Ownership, Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz chart these changes, explore quite how widely they are spread – from the music and films we listen to and watch to the computer systems that run our cars, fridges and coffee makers – and describe in an often disturbing way how this threatens our autonomy, privacy and whole understanding of our place in the world. It is a book that is deep, unsettling and at the same time humorous and entertaining – and well worth reading.

The core of the book, as its title suggests, is a detailed examination of the nature of ownership in the increasingly digital world. Perzanowski and Schultz start off by providing a fine summary and analysis of both how clouds and content streaming work and the implications in terms of ownership and rights. It is a complex, tangled web of law and technology – indeed, the complexity and tangle is part of the point – but The End of Ownership does its best to map out that web, and help to make sense of it, at least in so far as that can be done. This last point is critical. As the book shows quite beautifully, a lot of this makes very little sense, and there is a perverse incentive for many of those involved to keep the whole story as obscure and unfathomable as possible. This analysis – detailed and impressive – shows how the combination of law and technology works against the users. That is, it works against us: as the authors observe, “aggressive intellectual property laws, restrictive contractual provision, and technological locks have weakened end user control over the intangible digital goods we acquire”.

The End of Ownership is excoriating on that all too familiar piece of unread legalese, the End User License Agreement (EULA) that underpins much of the legal problem – including gems such as the revelation that Apple iTunes’ terms and conditions include prohibitions on the development of nuclear weapons. As the authors point out, these documents are not just rarely read, but it would be absurd to suggest that they should be: “Who in their right mind would read a 19,000-word license before making a 99-cent purchase from iTunes?”

Licences, as Perzanowski and Schultz explain in depth, “create considerable uncertainty about precisely what we get for our money”. What they also make clear is that the system is designed for the sellers, not the buyers, and that the sellers have an interest in generating and maintaining that uncertainty. Indeed, uncertainty and confusion is part of the whole point, and part of how people are kept sufficiently off balance to be swept away by the tide of changes. Those changes are considerable – from the shift of content to the cloud and the shift from “ownership” to licensing and to streaming, to the implications for the internet of things and the disturbing impact of patents and digital rights management (DRM) on products such as printer cartridges and coffee machines.

One of the issues that Perzanowski and Schultz highlight is the problem of potential price discrimination. “Information about each potential customer’s preferences, needs, buying habits, bank account, physical condition, and emotional state would give the seller real-time information about exactly how much they are willing to pay for a particular product. Running late? Expect higher gas prices. Parched after a long run? Expect to pay twice as much for that bottle of water.”

The assumption that price discrimination works in favour of poorer customers – often used to argue in favour of more price discrimination – is, as Perzanowski and Schultz demonstrate, a false one. Indeed, the opposite is very often the case. All that matters in practice is what is in the interests of the sellers.

The current system of licensing enables and supports this kind of price discrimination – and in the current data-filled and computer-dependent world, other equally disturbing possibilities are growing with immense rapidity. There is very little in our modern lives that does not have a digital aspect – and that means that the potential for harm is growing and broadening all the time. The harm includes significant problems for privacy and autonomy; for our freedom of speech and our access to information. Privacy is lost as our reading, watching and other habits are tracked, and censorship is enabled by the technical and legal possibility of works being deleted, edited or replaced without our consent or opportunity to react.

There is a particularly interesting section on libraries. The End of Ownership emphasises both the importance of libraries and the impact on them of the move from physical to digital books (and music, films, etc) and the corresponding changes in rights. Things such as e-books that self-destruct after 26 loans are just the beginning of what can be possible. Some of the critical benefits of libraries – as archives, as places where information can be accessed with privacy, for the poor as well as the wealthy – are also potentially under threat in this new “ownership” world. If authorities get easy access to records of reading habits and more, libraries can become tools of oppression, and will certainly no longer be able to perform the critical societal function that they currently do. As Perzanowski and Schultz put it: “How does a library expand the public’s understanding and engagement of materials when they belong to someone else and sit on remote servers they cannot access?”

The legal and technological analysis in The End of Ownership is illustrated throughout with apposite examples – from Amazon’s “Orwellian” remote deletion of Nineteen Eighty-Four from people’s Kindles to the coffee machines that refuse to brew unless the “correct” brand of coffee is used. The End of Ownership is not a dry legal text – which is not to say that the legal work it offers is not accurate and erudite – but one grounded in the realities of daily life for many of us. Moreover, the whole book is written attractively and with wit and humour. The affectionate relating of Taylor Swift’s break-up with Spotify – and the reasons behind it – is one example of those strengths, and the authors demonstrating the breadth of choice available to consumers by juxtaposing Jean-Luc Godard and Jean-Claude Van Damme was another that raised a laugh in this reviewer.

The authors’ likening of modern DRM systems to the book-burning “firemen” of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 is especially well done.

It is not a coincidence that The End of Ownership does not have a question mark at the end of the title. Perzanowski and Schultz are not setting out some possible future dystopia, but describing something that is already here and already having an impact on our lives. Although the solutions and reforms that they put forward in the final sections of the book are a little less convincing than their analysis of the problem, they should still be taken very seriously – as should The End of Ownership itself.

Paul Bernal is lecturer in IT, IP and media law, University of East Anglia Law School, and author of Internet Privacy Rights: Rights to Protect Autonomy (2014).

The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy

By Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz

MIT Press, 264pp, £22.95

ISBN 9780262035019 and 2335942 (e-book)

Published 16 December 2016

The authors

Aaron Perzanowski, professor of law at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, “was born in Wheeling, West Virginia and primarily raised in nearby Bellaire, Ohio – a small village in Appalachian coal country. Although I wasn’t raised in the most intellectually supportive community, I did absorb an appreciation for physical labour, tangible results and durable goods that has, in some ways, expressed itself in my thinking and writing about ownership.”

As an undergraduate, he studied philosophy at Kenyon College in Ohio. “Kenyon is a stunningly beautiful but physically isolated place. For me, it encouraged a period of reading, reflection and engagement with ideas. Kenyon’s curriculum and philosophy prioritize writing, and I credit my time there for building the foundation of whatever ability I have as a writer.”

His shift to law came in his early twenties, when he “developed an interest in the role technology played in regulating our behavior and in turn the ways in which law was enlisted to regulate technology”. Law schools such as that at the University of California, Berkeley “seemed to be the places where serious conversations about those overlapping regulatory frameworks were happening. So I chose to study as a way to satisfy my curiosity. As it turns out, analytic philosophy was ideal training for the construction and deconstruction of arguments that law school demands.”

Asked about the most recent music purchase he made, Perzanowski says: “I tend to buy new music primarily on vinyl, although I do sometimes pay for digital downloads from Amazon and Apple. My most recent purchases were Leonard Cohen’s You Want It Darker and John K. Samson’s Winter Wheat, both of which make for good listening as the chill sets in in Cleveland.”

Are there any digital business he does not patronise as a customer or user because of concerns over privacy, the ownership (or non-ownership) of goods purchased, poor labour relations/lack of unionisation, inadequate compensation of musicians or other ‘content providers’, or other such issues?

“One downside of studying these sorts of services is the realization that their pro-consumer benefits come at a cost. So I use Uber, but feel guilty about the exploitation of its drivers. I download ebooks from Amazon, knowing full well that their ‘Buy Now’ button deceives millions of consumers. In some ways, that’s what we hope the book can achieve. We don’t aim to change consumer behaviour or convince readers that particular services should be abandoned or boycotted. Instead, we want consumers to be mindful of their benefits, but also their many hidden costs.”

What gives him hope?

“I’m a pessimist by nature. But I think there is value in identifying threats to our shared values, if for no other reason than to document the evolution of those values over time. That said, I do hold out some hope that, on occasion, we can be persuaded to recognise and act in our collective self-interest. The book reflects this tension. The picture it paints reveals the slow, silent erosion of our personal property rights, but it also outlines several potential avenues for reform.”

Jason Schultz, professor of clinical law at New York University School of Law and co-author of The End of Ownership, was born and raised in Berkeley, California. “I suppose being close to Silicon Valley made me more attuned to the ways the technology culture converged and diverged from other cultures,” he comments.

He took his undergraduate degree at Duke University, majoring in public policy and gender studies, both of which “utilised critical analytical approaches to social problems”.

Schultz was formerly senior staff attorney at the Electronic Frontier Foundation. “I learned a lot at EFF, including how often the social and economic implications of a new technology or a new legal rule can be overlooked until it is too late. Defending digital consumer rights has always been a focus of EFF, and one I was proud to be part of.”

Asked if his students are worried about not “owning” consumer goods, he says that “like most digital consumers, they don’t spend much time focused on these questions because the vendors are very good at hiding the legal and technological mechanisms that undermine ownership deep within computer code or the lengthy legalese of an End User License Agreement. Once you highlight these restrictions, most of my students are pretty outraged.”

What courses of action would he recommend consumers take if they are concerned about the issues detailed in The End of Ownership?

“There is nothing fundamentally wrong with having different modes of ownership. In fact, many consumers prefer more ephemeral possessory interests, such as access to music via streaming services such as Spotify. The key is to give consumers both clear choices and protections for the benefits that ownership has offered, such as the ability to sell or donate something once you’ve finished it, the right to read, watch or use it privately without being tracked, or the right to consumer it on the device of one’s choice.”

What gives Schultz hope?

“There are a lot of judges and policymakers who care deeply about consumer rights. Solutions to these problems are not far-fetched or otherwise unobtainable. We just need to act on them.”

Karen Shook

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Clouds in my coffee

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login