What is the relationship between the term “Holocaust” and the set of commitments, processes, events and acts that it has come to connote? How should this history sit within wider discussions of what it means to be Jewish and a citizen of the world? These are the questions that underpin Deborah Lipstadt’s short book. Not least because early post-war attempts to make sense of the events were conducted in a number of different languages – a reflection of the variety of European Jewish heritages – it took some time to settle on a standard idiom. The difficulty of establishing the field was compounded by the marginal status of most survivors after the war, the desire of many to prioritise establishing new lives, and the general indifference of universities, publishers and wider national publics.

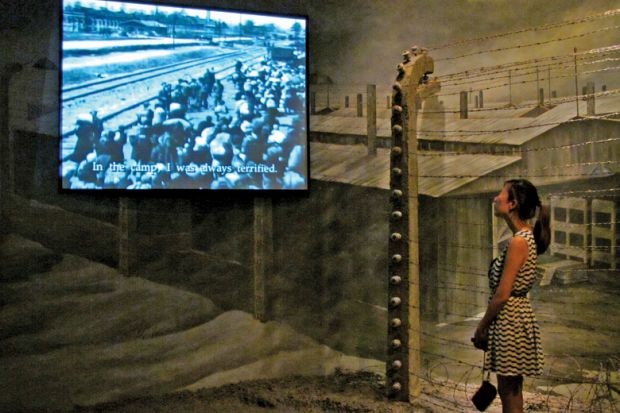

Nonetheless, as Lipstadt traces, the pioneering efforts of figures such as Philip Friedman and Raul Hilberg, combined with shifts in the wider culture provoked by the Eichmann trial and the Arab-Israeli wars, created a context in which the field we now recognise as Holocaust studies could coalesce. However, even as it consolidated itself, rifts and divisions opened up. Alliances with other groups that had suffered acts of massive historic violence, most obviously the African American community, came under strain. The American far Right pushed an agenda of Holocaust denial. Yet the Holocaust established a place at the centre of Jewish-American historical consciousness. The creation of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum was the most visible marker of this.

The book is very much an account of an American discourse on the Holocaust, and one in which Jewish voices take centre stage. For those on Jewish studies programmes in US universities, it will serve as a helpful introduction to the main trends since 1945. Yet the book’s strengths are also its weaknesses. While Lipstadt explores aspects of Christian-Jewish dialogue, and the ways in which American-Jewish understanding of the Holocaust was shaped by the Arab-Israeli conflict, the contributions of non-American voices, transnational flows of ideas and the dynamics of globalisation generally receive very little acknowledgement. The most obvious marker of this is the scholarly apparatus, which contains barely any reference to scholarship produced outside of a particular set of North American conversations. As a result, the focus feels a little parochial in places.

This is compounded by the unmistakably particularist agendas of the account as it moves towards contemporary concerns. There has always been a strong tension between habits of thought that anchor the need for more assertive Jewish identities and support for muscular Israeli politics in a sense of the Holocaust’s unique status, and arguments that foreground a more universalist critique of radical nationalism and racism wherever they rear their heads. Lipstadt traces both sides of the argument over singularity, and suggests that this is now a stale debate. She is right: the most interesting discussions have long since moved elsewhere.

Yet one can always feel the quickening of a scholar’s heart in the movements of their pen, and it is not difficult to work out where Lipstadt’s instincts lie. While rightly rejecting an inflationary appropriation of the Holocaust by those with contemporary axes to grind, her conclusions assert a critique of contemporary racism that focuses almost solely on (European) anti-Semitism, and a set of political claims that feel disappointingly partisan. Given where we now are, the assertion that “the Holocaust should not serve as a tool for ensuring generosity, [or] promoting vigilance” feels singularly ill-timed.

Neil Gregor is professor of modern history, University of Southampton.

Holocaust: An American Understanding

By Deborah E. Lipstadt

Rutgers University Press, 220pp, £93.50 and £29.50

ISBN 9780813564777, 4760 and 4784 (e-book)

Published 30 August 2016

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login