The late leader of Singapore, Lee Kuan-yew, said the problem with Japan and China is that the former never remembered anything, and the latter never forgot. But as veteran academic Ezra Vogel’s latest work makes clear, Sino-Japanese relations these days could be summarised by two phrases: “Sorry” (which Japan is forever accused of not saying properly) and “Thank you” (China never fully expresses its gratitude for the huge assistance Japan has given it since the post-1978 reforms). For two nations with such complex codes of formality, it is these issues over acts of courtesy that show how far apart they are.

For one of the world’s key relationships, the Sino-Japanese one is woefully neglected, with few comprehensive comparative studies in English. One reason is that scholars concentrate either on one or the other. Few manage to master the languages and the source materials of both. This is compounded by the fact that those best placed, Japanese and Chinese scholars, seem unwilling or incapable of reaching a shared view of how to analyse their vexed histories. Well-intentioned attempts in the 2000s to put scholars from the two countries together to produce a joint historic narrative led to much fanfare and little output. The task in the end proved too onerous.

Vogel is in a great position to undertake some of this work, but it is clear from this book, produced in his ninth decade, that it is a mighty undertaking even for him. Two chapters, about Japanese impact on the modernisation of China in the 19th and 20th centuries and about the lead-up to the Second World War, are co-authored with Pamela Harrell and Richard Dyck respectively. Much of the second half of the book relies on the immense research that Vogel did for his biography, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (2011). In particular, the chapters dealing with the renaissance of bilateral relations from 1978, when China started to open up to the outside world economically after the decades of Maoist enclosure, have the same densely empirical, narrative style as the Deng work.

The value of this book, however, is not in its account of modern times, but in supplying much-needed historical context from the earliest, less-well-understood eras of contact. In the first two chapters, one issue becomes clear: from the simple fact that Japan was an island, and earlier dynasties in the territory where the People’s Republic of China now is had a continental diversity and complexity, there were intrinsic differences between the development and internal structures of the two right from the start. In the era of most profound cultural borrowing by the emerging, consolidating Japanese nation state, from 600 to around 838 AD, Vogel deploys the term “China”, although the entity he is talking about (largely the Tang imperial dynasty) was markedly different in size and extent to the country that exists today. This is the main reason why some Sinologists have called this China a civilisational force, with all the amorphousness that implies, rather than a geographically bounded entity.

As a civilisation, the Tang’s impact on Japan was profound, with the migration eastwards of Confucian, Buddhist and Daoist views of the world, and, perhaps most profound, the adoption by Japan of Chinese characters. This remarkable dissemination of influence poses a question that remains pertinent to this day: how is it that two powers that shared so much at an early stage of their development went on to suffer such profoundly tragic disagreements and misunderstandings later? Did this shared root give them nothing by which to avoid the almost existential clashes they experienced in the early to mid 20th century? Were they even a cause of this struggle?

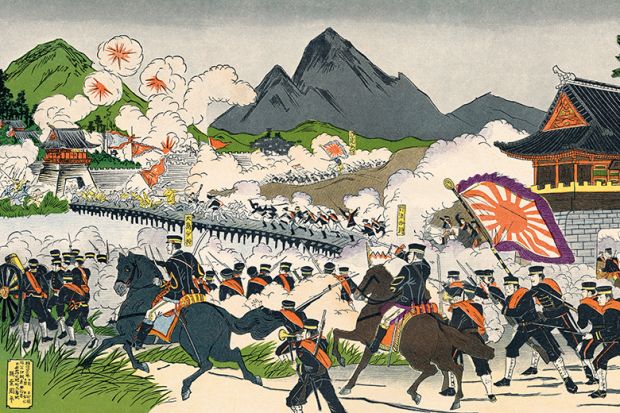

It is true, as Vogel’s narrative of the 9th to 19th centuries shows, that for almost a millennium contact between the two was surprisingly limited, and oddly one-sided. The only battle ever fought on Japanese soil by forces from the Chinese mainland to this day was during the Mongolian Yuan dynasty in the 14th century. The engagement thereafter, as and when it happened, was mostly of Japan reaching back into China. This figures almost as payback for the early era when culturally Chinese forces reached so deeply into Japan. It was also characterised by intensifying hostility, particularly after the modern era from the Meiji restoration in the 1860s onwards when, as a precursor to China’s experience almost a century later, Japan emerged from isolation by modernising rapidly, and expanding its footprint across the region, and more deeply into the world.

It is inevitable that the climax of this tragic clash, the devastating Sino-Japanese War (1937-45), looms large over much of the latter half of the book. It is a story that even those with little knowledge of Asia are aware of. The ominous augurs of it started from the end of the 19th century and the first Sino-Japanese war of 1894-5. The second conflict was much larger, with a devastating impact on China and its people. It is this war that continues as a live issue to this day, the resentments it created seemingly never disappearing. No form of apology from Japan is ever sufficient to compensate for Beijing, even though by the latest count there have been about 30 attempts by Japanese leaders.

The Japanese could argue for forgiveness through their actions rather than words. As Vogel notes, from 1979 to 1999, Japan provided a staggering 56 per cent of all aid China received from other countries as it redeveloped and modernised. Without this, China would not be remotely close to the position it is in today. For all of this, though, Beijing’s “Thank you” is as sotto voce as Tokyo’s “We’re sorry.”

The importance of this book – by one of the great Asian specialists from the US of the modern era – is in alerting what will hopefully be a wide readership to how complex, and crucial, Sino-Japanese relations are, and how any complacency about the two being able to get on easily and unproblematically can be cured by attending to their long, complex and frequently acrimonious history. The book’s ending attempts to be optimistic. But readers should worry. There is a moral for others in Japan’s deep engagement with a China it hoped would become a closer ally and friend, while having all the knowledge of Chinese culture, language and business seemingly needed to achieve this. The consensus is now that it has ended up with a partner made stronger by its assistance, and therefore much more able to oppose and confront it. The key question left at the end of this book is whether the experience of the rest of the world with China will be the same – or whether this is a relationship so exceptional that no one else can, thankfully, duplicate it.

Kerry Brown is professor of Chinese studies and director of the Lau China Institute, King’s College London and author of China’s Dreams: the Culture of the Communist Party and the Secret Sources of its Power (2018).

China and Japan: Facing History

By Ezra F. Vogel

Harvard University Press, 536pp, £28.95

ISBN 9780674916579

Published 30 July 2019

The author

Ezra F. Vogel, Henry Ford II professor of the social sciences emeritus at Harvard University, was born in Delaware, Ohio and attended Ohio State University. He went on to do a PhD in sociology at Harvard and then spent two years in Japan to learn the language and carry out the interviews with families that would form the basis for his book Japan’s New

Middle Class: the Salary Man and His Family in a Tokyo Suburb (1963).

In 1961, after a short period at Yale University as an assistant professor, Vogel joined Harvard as a postdoctoral fellow studying Chinese language and history. He was promoted to a professorship in 1965, took two years’ leave of absence to serve as National Intelligence Officer for East Asia and returned to Harvard until nominal retirement in 2000, although he continues to be very active as a scholar.

Throughout his career, Vogel has spent a great deal of time in Asia, and lectured widely in Chinese and Japanese as well as English. He is highly unusual in having produced major works about both China and Japan, and how the West should respond to them, before turning to the complex relations between them.

On Japan, Vogel is the author of Japan as Number One: Lessons for America (1979), whose translation into Japanese proved the all-time best-selling work of non-fiction by a Western author; its follow-up Comeback: Building the Resurgence of American Business (1985); and Is Japan Still Number One? (2000).

In 1987, Vogel was invited by the Guangdong Provincial Government to spend eight months studying its economic reforms. His findings were published as One Step Ahead in China: Guangdong under Reform (1989). Related themes are explored in some of his other works, including The Four Little Dragons: The Spread of Industrialization in East Asia (1991) and Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (2011).

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Thanks and sorry are hard to say

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login