Geoffrey Alderman, professor of politics and contemporary history, University of Buckingham

John Cooper’s The Unexpected Story of Nathaniel Rothschild (Bloomsbury Continuum) is a brave attempt to chart the life of a secretive Anglo-Jewish grandee (more British perhaps than he was Jewish) who led the attack on David Lloyd George’s “People’s Budget” of 1909, but who ignored the Welshman’s personal invective and supported him unstintingly when war broke out five years later. In Richard III: A Ruler and his Reputation (Bloomsbury Continuum), and for the benefit of us non-medievalists, David Horspool cuts to the chase: despite all the attempts at rehabilitation, Richard III was a villain, but probably no more of a villain than his villainous baronial contemporaries. Rooted in the sources, this is, above all, a jolly good read.

David Andress, professor of modern history, University of Portsmouth

The image of the violent mob is one that haunts my field of study, so Micah Alpaugh’s Non-Violence and the French Revolution: Political Demonstrations in Paris, 1787-1795 (Cambridge University Press) is a valuable contribution showing that a widespread culture of democratic protest and demonstration flowed almost continuously around the bloody confrontations we usually acknowledge. It is the sort of point that Terry Pratchett would have appreciated, and showed awareness of, in so many of his books. With his passing, we have lost a great humane voice of reason and justice, and The Shepherd’s Crown (Doubleday) marks the end of a literary era.

Dorothy Bishop, professor of developmental neuropsychology, University of Oxford

I would like to recommend two non-fiction books, both of which give fascinating insights into the process of doing science. In his autobiography, A Scientist in Wonderland: A Memoir of Searching for Truth and Finding Trouble (Imprint Academic), Edzard Ernst explains how use of the scientific method led him to change his mind about the effectiveness of the alternative medicines he grew up with, and then how his quest for evidence led him into conflict with powerful forces who were determined to wreck his career. In The Hunt for Vulcan: And How Albert Einstein Destroyed a Planet, Discovered Relativity, and Deciphered the Universe (Random House), Thomas Levenson creates a wonderful narrative spanning three centuries, from Newton to Einstein, showing how an anomaly in the orbit of Mercury led astronomers to postulate a hidden planet, Vulcan – and because we are biased to see what we expect, it took years before it was debunked. For 2015 fiction, nothing can beat Edna O’Brien’s extraordinary masterpiece The Little Red Chairs (Faber & Faber). A stranger comes to a small Irish community and nothing is ever the same again. The writing is so vivid that you are drawn into every event. A book that stays with you long after you put it down.

Jennie Bristow, lecturer in sociology, Canterbury Christ Church University

Age-old questions about what people read, why they should read, and whether they are reading too much or too little continue to preoccupy parents, educators and politicians. Frank Furedi’s intellect-affirming Power of Reading: From Socrates to Twitter (Bloomsbury) places the “dangerous” character of reading – its ability to inflame passions and raise questions – at the centre of these debates. In Margaret Atwood’s latest dystopia, The Heart Goes Last (Bloomsbury), Stan and Charmaine quickly realise the cost of trading their freedom for the safety and comfort of incarceration. Classic Atwood, written with a lightness of touch that makes you laugh as well as think.

Jacqueline Broad, senior research fellow in philosophy, Monash University, Australia

Mary Wollstonecraft is typically depicted as a romantic historical figure, but Lena Halldenius’ superb Mary Wollstonecraft and Feminist Republicanism: Independence, Rights and the Experience of Unfreedom (Pickering & Chatto) presents her as a serious theorist of freedom for women and other enslaved social groups. It is a truly consciousness-raising work that made me feel rather guilty about reading it on a banana lounge in Bali. Better suited to the banana lounge was Nicci French’s Friday on My Mind (Penguin). It has a bloated corpse in the Thames, a wrongly accused suspect and a plethora of improbable plot twists (how did the heroine get that annoying toddler to sleep?). Crime writing at its guilty-pleasure best.

Donald Brown, MPhil student in modern British and European history, University of Oxford

For those interested in American race relations, read Ta-Nehisi Coates’ Between the World and Me (Spiegel & Grau). This memoir, addressed to Coates’ teenaged son, details how much fear of bodily harm weighs on the minds of African Americans as they mature into adulthood. Moreover, it shows how that fear marks their psyche for life. Gary Wilder’s Freedom Time: Negritude, Decolonization, and the Future of the World (Duke University Press) reveals important insights into two of the most important thinkers of postcolonial politics, Léopold Sédar Senghor and Aimé Césaire, and how they imagined self-determination for their formerly colonised peoples via non-national forms of decolonisation.

Geert Buelens, professor of modern Dutch literature, Utrecht University, the Netherlands

There is still a world to discover in cultural studies. In Noise Uprising: The Audiopolitics of a World Musical Revolution (Verso), Michael Denning demonstrates what happens when we reframe the debate about music, politics and technology in a global context. A free e-book of Herman Gorter’s Poems of 1890: A Selection (UCL Press) is a rare gift to the English-reading world. Translating highly lyrical poetry is probably the most challenging thing for a translator, but time and again Paul Vincent succeeds in suggesting something of the genius of the most important Dutch lyrical poet.

Douglas Chalmers, senior lecturer in media and journalism, Glasgow Caledonian University, and president, UCU Scotland

I have found Helena Bassil-Morozow’s The Trickster and the System: Identity and Agency in Contemporary Society (Routledge) an invaluable resource for understanding what makes change happen, and how disruptive agents of change operate in society. It is a book about “similarity and difference” and the relationships between the individual and authority – all laid bare here in a consummate manner. For relaxation: J. K. Rowling is not just for kids. Career of Evil (Sphere), the third of Rowling’s volumes written as Robert Galbraith and featuring the idiosyncratic detective Cormoran Strike and his under-appreciated companion Robin Ellacott, is just what is needed as the dreaded Christmas season approaches. And I love the fact that there is clearly a fourth volume on its way.

Marcus Chown, author of What a Wonderful World: Life, the Universe and Everything in a Nutshell, tweets for the National Health Action Party

The protagonist of Emma Healey’s blackly comic murder mystery Elizabeth is Missing (Penguin) is suffering from dementia. The author brilliantly depicts a mind, still utterly rational, that is struggling to draw conclusions from the moth-eaten cloak of her memories. It does for Alzheimer’s what Mark Haddon’s The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time did for autism. NHS for Sale: Myths, Lies & Deception by Jacky Davis, John Lister and David Wrigley (The Merlin Press) is the story of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 and what was concealed from the electorate in the 2010 election. Shockingly, it removed the government’s duty to provide universal healthcare, thus beginning the stealth dismantling of the NHS. The overwhelming opposition of the medical profession to the act went unreported, so this book is of critical importance to warn the public.

Catherine Clinton, Denman chair of American history, University of Texas, San Antonio, and international research professor, Queen’s University Belfast

Christine Leigh Heyrman’s American Apostles: When Evangelicals Entered the World of Islam (Farrar, Straus & Giroux) is an elegantly conceived, meticulously researched portrait of the adventures of the first generation of New England missionaries to criss-cross the Levant more than a century ago. Heyrman’s engaging narrative sheds light on modern US attitudes towards Islam, offering insights laced with judicious, compelling calibration. Mary Norris’ Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen (W. W. Norton) is half-memoir, half copy-editor’s lament – blue pencils at The New Yorker – and sheer delight. Norris’ self-deprecating and hilarious confessional dives deep and comes up with a bounty of pearls: what to do with pronouns when a brother becomes a she, how to deal with dashes and ellipses, the semicolonic dilemma, etc.

Frank Close, professor of physics, University of Oxford

Jon Butterworth’s Smashing Physics: Inside the World’s Biggest Experiment (Headline) gives an insider’s view of life at Cern chasing the Higgs boson. The author’s enthusiasm would excite any reader to want to be part of the adventure, too, and this book will surely inspire a new generation into science. Front Runner (Michael Joseph) is my fiction choice, if only to show there is life after physics. The author, Felix Francis – the son of Dick Francis – was a physics teacher before he took over his father’s mantle and now produces a thriller a year. If only I could write 1,000 words every day.

James T. Crouse, adjunct professor of aviation law, Duke University

Who were these two Ohio bicycle mechanics that changed the world? What was the source of their genius, what challenges did they face, and how did they figure out what no one else did? In The Wright Brothers (Simon & Schuster), David McCullough answers all these questions by taking us into Wilbur and Orville Wright’s personal and technical world. The name Alexander Butterfield is lost in history, even though the presidential aide’s revelations about the White House taping system undoubtedly changed history. In The Last of the President’s Men (Simon & Schuster), Bob Woodward tells us about this most honourable man and shows us the bizarre world of Richard Nixon, offering additional insight into the personality and politics of a complicated, enigmatic and tragic president.

Alison Matthews David, associate professor in the School of Fashion, Ryerson University, Canada

Categorising clothing into “male” or “female” attire is repressive and often arbitrary. Clare Sears’ powerful book Arresting Dress: Cross-Dressing, Law, and Fascination in Nineteenth-Century San Francisco (Duke University Press) draws on transgender theory to question the introduction of laws that made donning “a dress not belonging to his or her sex” a criminal offence on the American frontier. In Confidence (Biblioasis), Russell Smith gives us glimpses into the lives of characters as “sweet and bitter” as the ridiculously named Smokedrop cocktails they imbibe. Canadians are perceived as naive do-gooders, but Smith pens us with some of the dark glamour that some of us self-consciously aspire to.

Elizabeth Dobson, senior lecturer in music technology, University of Huddersfield

In Singing the Body Electric: The Human Voice and Sound Technology (Ashgate), Miriama Young presents a brilliant account of how the voice has been preserved, transformed and even imagined in relation to technology. The 13-page list of electro-vocal pieces alone is a superb resource. Felicia Day’s You’re Never Weird on the Internet (Almost): A Memoir (Touchstone Books) is the biography that I would love to gift every girl with ideas and ambition…because permission is not required. This “weird” geek internet star, actor and chief content officer for Legendary Entertainment is a woman who, according to Joss Whedon, who wrote the foreword, absolutely “knows her way”.

Danny Dorling, Halford Mackinder professor of geography, University of Oxford

Top academic book: Linsey McGoey’s No Such Thing as a Free Gift: The Gates Foundation and the Price of Philanthropy (Verso). Especially recommended if you work in an institution that relies on a great deal of philanthropy. When I was last in the United Nations building in New York I heard “Bill would not like that”, said in response to a progressive suggestion. Even if it were meant sarcastically, it spoke volumes. McGoey’s book explains why. For pleasure: Andrew Marr’s Head of State (Fourth Estate). Especially for calling the University of Oxford “that crowded, clucking duckpond of vanity and ruffled feathers” – spot on!

Helga Drummond, professor of decision sciences, University of Liverpool Management School, and recent visiting professor of business, Gresham College

One of this year’s better (and more disturbing) business books is Matthew Syed’s Black Box Thinking: The Surprising Truth About Success (John Murray). The most intriguing insight centres on pausing to consider what you might not be hearing and seeing before rushing to judgement. Yet for a much more surprising truth about success, try Charles Moore’s Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume Two (Allen Lane). Although its subtitle is Everything She Wants, the book shows how the line between success and failure may be wafer-thin and fleeting. Forget “making a difference” and other leadership clichés. When weak, persist, and exploit even the smallest advantage.

Megan Dunn, president, National Union of Students

I loved the mixture of quirkiness and sadness in Miranda July’s collection of short stories a few years ago, and she delivers on her massive potential in her long-awaited debut novel, The First Bad Man (Canongate). In its look at loneliness and the never-ending complexity of human relationships, I found a heart-breaking and hilarious exploration of womanhood. When the victims of austerity are rendered as statistics, it is easy to lose sight of the humans behind the numbers. Mary O’Hara’s desperately sad and angering book Austerity Bites (Policy Press) reminds us what horrendous impacts governmental policy has on actual people, in this collection of personal stories from across the country. It reminded me why I do what I do.

Mary Evans, centennial professor at the Gender Institute, London School of Economics

Reading fiction is, for me, getting ever more difficult because there is no reliable way to make a choice. Every novel has a back jacket covered with extraordinary praise, while the range of book reviewers in the broadsheet press is confined to a small circle of people from an equally small social world. Hence the two books here are both non-fiction, with judgements arguably more closely related to the content of the books and less to the desired self-identification of the reviewer. In 2015, I very much enjoyed Jill Leovy’s Ghettoside: Investigating a Homicide Epidemic (Bodley Head) and Mike Savage’s Social Class in the 21st Century (Pelican). Leovy’s book is a study of the work of a group of detectives in Los Angeles faced with a high murder rate and an equally high rate of murders that are not investigated: the murders of young black men. The detectives try their best to make every life count, but black lives do not, it would seem, always count for very much. Being seen as important enough to matter might also be part of what Savage describes as the “new politics of class”. Both these books are written with verve and energy; they engage with our present with real imagination.

John Field, emeritus professor in the School of Education, University of Stirling

This is a year in which class differences have become very visible indeed. Mike Savage’s Social Class in the 21st Century (Pelican) uses the findings of the Great British Class Survey to show us how culture, money and status help to explain our position and behaviour. Unsurprisingly, education forms a central mechanism in holding privileged positions together. The durability of Britain’s elites would have astonished and disappointed the assorted dreamers, workmen and political exiles who feature in Nigel Todd’s Roses and Revolutionists: The Story of the Clousden Hill Free Communist and Co-operative Colony 1894-1902 (Five Leaves Publications), living out their dreams of a peaceful socialist future on a hill outside Newcastle.

Wendy R. Flavell, professor of surface physics, Photon Science Institute, University of Manchester

I am not a fan of biography, but I am proud to work in a building named after one of our most brilliant mathematicians. This fact made me suspend my scepticism to read Prof: Alan Turing Decoded (The History Press), by his nephew Dermot Turing. I was richly rewarded by a very human but authoritative account packed with photographs, anecdotes, letters and examples of Turing’s dry but poignant humour, as in the postscript of a letter to a friend in early 1954: “I’m getting slightly hetero, but it’s fearfully dull.” In common with many, I dashed out to the campus bookshop on 14 July to buy the long-awaited second (or first?) novel by Harper Lee, Go Set a Watchman (William Heinemann). In Scout’s return to Maycomb I found a real, complex and sobering story of how polarisation in society can increase even in the face of legislation to promote equality. In the wake of recent events in Charleston, it left me reflecting on the slow pace of change in the intervening 60 years. I have thoroughly enjoyed my copy of A Natural History of English Gardening (Yale University Press): in a vast and richly illustrated coffee-table tome, Mark Laird unfolds the history of English gardening in the 17th and 18th centuries, in the context of cultural changes and the developing understanding of natural history and plant husbandry. The contributions made by women – such as Mary Delaney’s wonderful botanical collages – are strongly represented.

Peter Fleming, professor of business and society, City University London

A future free from work might seem unrealistic, but it is actually the elephant in the room that Cameron et al. would rather you ignored. Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams’ fabulous study Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work (Verso) opened my eyes to the role technology might play in making society possible again. Everybody hated Morrissey’s novel List of the Lost (Penguin), but it’s brilliant. This allegory takes us back to 1975, and students of Thatcherism and Reaganomics will note the significance. Four young athletes encounter their grotesque future in a forest and murder him. Human qualities are thrown on the bonfire, making this laconic fable the perfect Orwellian companion for the neoliberal age.

John Foot, professor of modern Italian history, University of Bristol

I am going to cheat and choose two “work” books. Marco Pastonesi’s Diavolo di un corridore: Corse, battaglie e miracoli di Renzo Zanazzi (Italica Edizioni) is a lyrical and hilarious portrait of a journeyman cyclist in post-war Italy. Matthew Klugman and Gary Osmond’s Black and Proud: The Story of an Iconic AFL Photo (New South Books), meanwhile, is a brilliant study of how one indigenous sportsman took on the racists not only in the crowd but in Australia as a whole. My other choice has haunted me since I finished it. Åsne Seierstad’s One of Us: The Story of Anders Breivik and the Massacre in Norway (Virago) is an uncompromising and brave account of a day of horrific violence in 2011. Seierstad’s study not only offers vivid portraits of the victims, but takes us deep into the strange – but oh so normal – world of Breivik himself.

Louise O. Fresco, president, Wageningen University and Research Centre, the Netherlands

Even better than reading is writing. So no greater pleasure exists for any professional educator, of whatever discipline, to read about the art of writing. Mary Norris’ Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen (W. W. Norton) delighted me with its playful and thought-provoking journey through pronouns, hyphens, semicolons and much more that matters in life. In the host of books that decry the loss of traditional foods and landscapes, Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing’s The Mushroom at the End of the World (Princeton University Press) stands out, notwithstanding its subtitle, On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. No simplistic nostalgia here, but a fascinating account of the biology, ecology, genetics and anthropology of the world’s most valued mushroom, the matsusake.

Robert Gellately, Earl Ray Beck professor of history, Florida State University

Among my favourite books this year is Peter Longerich’s Goebbels: A Biography (Bodley Head), weighing in at more than 1,000 pages. Using Goebbels’ novel, his massive diary and more, the author makes this biography seem fresh, especially Goebbels’ youth, psychology, relationships with women, path to Nazism and pre-1933 work in Berlin. Hardly less weighty is Wolfram Pyta’s Hitler: Der Künstler als Politiker und Feldherr: Eine Herrschaftsanalyse (Siedler), which integrates Hitler’s preoccupations with art, war and history. The most original book on Hitler in years, and bound to interest general readers and experts, it glistens with insights, such as why Hitler, hoping for a miracle, refused to surrender.

Liz Gloyn, lecturer in Classics, Royal Holloway, University of London

For work: Classical Traditions in Science Fiction (Oxford University Press), edited by Brett M. Rogers and Benjamin Eldon Stevens, is a stimulating and provocative collection of essays. Themes include the link between ancient literature and the earliest works of SF; SF and Classics in the early to mid-20th century; what happens when you set Classics in space; and how SF uses classical tropes to conduct thought experiments about problematic issues. For pleasure: Jennifer Adams’ Little Miss Austen – Emma: An Emotions Primer (BabyLit). A charming baby-friendly classic that uses Jane Austen’s characters to teach words associated with emotions. The colourful illustrations feature attention-grabbing faces; my son particularly enjoys the steam coming out of angry Mr Elton’s ears, and happy Miss Taylor’s cat. The source of a great deal of pleasure in our house.

Peter Goodhew, emeritus professor of engineering, University of Liverpool

We do not have enough engineers to deliver the future we want, or to overcome the challenges we know we face. A plethora of earnest reports tell us this and attempt to explain the unpopularity of engineering. In David Goldberg and Mark Somerville’s A Whole New Engineer (ThreeJoy Associates), we read about the foundation and success of Franklin W. Olin College in Massachusetts, which has broken the mould and is producing more and different engineers. Hurrah! For contrast (can I really mean relaxation?), I devoured The Joy of Tax: How a Fair Tax System Can Create a Better Society by Richard Murphy (Bantam). Now I have an inkling about government spending. Is it really true, as Murphy asserts, that nowhere in the UK university sector do we teach why we tax? Shame on us.

Neil Gregor, professor of modern European history, University of Southampton

I greatly admired Nicholas Stargardt’s The German War: A Nation Under Arms, 1939-45 (Bodley Head), which uses diaries, letters and similar materials to describe the ideological, cultural and emotional resources upon which ordinary Germans drew to sustain themselves, at home and at the front, through the Second World War. Having travelled widely in central Europe this year, I also warmed hugely to Joseph Roth’s The Hotel Years: Wanderings in Europe Between the Wars (Granta) – another wonderful volume of his beautifully observed journalism from the remains of the Habsburg Empire and beyond, and superbly translated (as ever) by Michael Hofmann.

John Harris, reader in the department of business management, Glasgow Caledonian University

Stephen Wagg’s The London Olympics of 2012: Politics, Promises and Legacy (Palgrave Macmillan) offers a most insightful analysis of some of the key issues that have frequently been ignored since the circus left town. Wagg highlights how such an event continues to engage us, but also disappoints those who were promised much more. Geraint Thomas won a gold medal in London and his book The World of Cycling According to G (Quercus) gives a nice insight into the life of a professional cyclist from the perspective of a proud Welshman and one of the most popular people in the sport.

Aniko Horvath, postdoctoral research associate in the School of Social Science and Public Policy, King’s College London

The great French anthropologist Marc Augé’s captivating novel Someone’s Trying to Find You (Seagull) takes us to contemporary Paris to join two strangers as they search through their past to give meaning to their present. Set against the alienated and transient “non-places” of “supermodernity” that Augé so often critiques in his anthropological work, this clever, moving and intriguing story takes us on a passionate quest for love, friendship and belonging. Ruth Wodak’s The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean (Sage) hits a much darker chord as Wodak takes us through the stages that led to the normalisation of nationalistic, xenophobic, racist, anti-Semitic and anti-refugee political and public discourse in the UK, Europe and the US. With such discourses playing on and with our fears, Wodak argues, we must stop being so damn scared and finally come to understand the “rhetorical traps” being set by right-wing ideologues. With the recent re-emergence of the “politics of terror”, her clearly written antidote could not be more timely.

Jo Johnson, Conservative MP for Orpington and minister of state for universities and science

Steve Silberman’s Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and How to Think Smarter About People Who Think Differently (Allen & Unwin) challenges conventional thinking about autism and encourages us to think in terms of “neurodiversity” – vital for anyone in a position of responsibility, whether as a parent, teacher, employer or policymaker. David Palfreyman and Ted Tapper’s Reshaping the University: The Rise of the Regulated Market in Higher Education (Oxford University Press) charts the changing relationship between government, the higher education sector and students over the past half century or so. Any such account will inevitably elicit a wide range of views, but this is a clear assessment of the sector’s strengths and challenges.

Richard Joyner, emeritus professor of chemistry, Nottingham Trent University

David Wootton’s The Invention of Science (Allen Lane) is outstanding. It details how, when and why the philosophical, intellectual and practical frameworks of modern science arose, and it sees off relativism in the process. While dealing wonderfully in broad sweeps, it offers a wealth of entertaining details. If you still find travelling by train a magical experience, Simon Bradley’s The Railways: Nation, Network and People (Profile) is for you. It gives a loving, witty and informed picture of everything from accidents (plenty of those) to the XP64 and from Aberdare and Armagh to York by way of Inverness, calling of course at Clapham Junction.

John Latham, vice-chancellor, Coventry University, Times Higher Education Awards University of the Year 2015

Adam Sisman’s John Le Carré: The Biography (Bloomsbury) is an easy-to-read insight into a complex individual, showing the separations of aspects and stages of life and the inevitable personal need to keep some things back. A reflection on a time past, but with uncanny similarities to today. Jeffrey Pfeffer’s Leadership BS: Fixing Workplaces and Careers One Truth at a Time (Harper Business) is a well-written narrative that questions orthodox approaches to leadership styles and delivery, and focuses on the power of information, evidence and determination to enable leaders to drive hard to succeed as many others have.

Mark Leach, editor of Wonkhe

In the unexpected political calm of the summer, Nick Robinson’s Election Notebook: The Inside Story of the Battle Over Britain’s Future and My Personal Battle to Report It (Bantam) gave us the inside track on the campaign. And as the personal is also truly the political, Robinson charts his own journey too, involving a cancer diagnosis and subsequent battle to bring the election to living rooms across the UK. Eric Schlosser has a remarkable ability to tell intricate and sometimes chilling real-life stories with verve and humanity. His Gods of Metal (Penguin) is a short work about the (in)security of America’s nuclear arsenal and is not only deeply fascinating but should also serve as an inspiration to journalists who look for ways to educate and entertain readers about the sometimes troubling world we live in.

Finn Mackay, senior lecturer in sociology, University of the West of England

Elizabeth Evans’ The Politics of Third Wave Feminisms: Neoliberalism, Intersectionality, and the State in Britain and the US (Palgrave Macmillan) is a practical and well-written book that does what it says on the tin – a rare find within academia. It uses the words of activists themselves, comparing the US with the UK, to untangle what self-defined “third wave” feminists mean by the concept and how they enact their politics. As for Hilary McCollum’s Golddigger (Bella Books), think a grittier Tipping the Velvet. Our hero Frances leaves home and lives as a man in 1840s America, pursuing the Californian gold rush; hence the title. The tale shifts back and forth between rural Ireland and the industrialising US – impeccably researched backgrounds that are perfect for this Sapphic adventure.

Caroline Magennis, lecturer in 20th- and 21st-century literature, University of Salford

Tom Walker’s study Louis MacNeice and the Irish Poetry of his Time (Oxford University Press) is a much-needed and meticulously referenced work on this vital poet, playwright and broadcaster. It sets MacNeice’s work productively in dialogue with both the great W. B. Yeats and lesser-known poets, and it is essential for anyone captivated by this most incorrigibly plural of writers. I greedily raced through Carrie Brownstein’s memoir Hunger Makes Me a Modern Girl: A Memoir (Virago), a book as raw and honest as the Kathleen Hanna documentary The Punk Singer. It takes you through fandom and family to the mighty Sleater-Kinney and Portlandia with a funny, sharp, feminist voice.

Randy Malamud, Regents’ professor of English, Georgia State University

From his 747 cockpit, Mark Vanhoenacker’s rapturous prose captures the splendour of the world beneath – night, water, waypoints, Greenland (pilots’ “best-loved sight in all the world”). Skyfaring: A Journey with a Pilot (Knopf) restores to aviation the wonder that has disappeared; best read, of course, aloft. At ground level, Owen Hatherley’s Landscapes of Communism: A History Through Buildings (Allen Lane) interrogates ideology and everyday life as he examines monuments and mausolea, television towers and metro stations (“palaces for the people”), post-Second World War restorative reconstruction and even Polish churches, to revisit Cold War-era antipathy towards “Soviet architecture”. Less monolithic, more polyvalent and richly historicised than conventional assessments, this revisionist aesthetic inspires excursions to Warsaw, Moscow, Bucharest…Fly there!

Gordon Marsden, Labour MP for Blackpool South and shadow minister for further education, skills and regional growth

The projects and politics of seaside regeneration, from the Georgians to 2015, and the symbiosis between quirkiness and Englishness in our coastal pioneers, are all wrapped up with salty exuberance in Tom Fort’s Channel Shore: From the White Cliffs to Land’s End (Simon & Schuster), a journey’s tale with echoes of John Betjeman and Alan Bennett. In The Face of Britain: The Nation Through its Portraits (Penguin), Simon Schama also explores the connections of individuals to our island story through five centuries of portraiture. Schama movingly delivers a metaphysical tour de force, meditating on the tensions between artist and subject and between capturing the transient and crystallising the eternal.

Doreen Massey, emeritus professor of geography, the Open University

One of the crying needs at the moment is to challenge the prevailing “common sense” of neoliberalism, especially its economic nostrums. Many oft-repeated truisms about tax do not stand up to serious scrutiny. Challenging them would open up the field for debate on economic policy. Moreover, tax is much more than economic policy – it is an element in the construction of our collectivity and in decisions about what kind of society we want. In The Joy of Tax: How a Fair Tax System Can Create a Better Society (Bantam), Richard Murphy takes on all this with gusto, moving from forensic deconstruction of the current common sense to a proposal for a chancellor’s statement that might set us on the road to change.

Peter Matthews, lecturer in social policy, University of Stirling

John Hills’ book Good Times, Bad Times: The Welfare Myth of Them and Us confused my students no end last year. Policy Press actually published it in 2014 but it has a publication date of 2015, so I answered endless emails asking how to cite it correctly. A cracking book that I have reviewed at greater length for Housing Studies journal, it is a forensic account of the contemporary UK welfare state and readable enough to be my dad’s Christmas present. I read Dan Davies’ In Plain Sight: The Life and Lies of Jimmy Savile (Quercus) – a gripping, horrifying account of Savile’s years of abusing – after reading Hannah Arendt’s Eichmann in Jerusalem for a theory book group in my school. I commented to the book group leader that the contrast was interesting: Savile was a monster, whereas in Arendt’s account, Eichmann’s trial failed to portray him as a monster; he was a stupid bureaucrat doing his job. But the books also parallel each other in another way: each offers lessons in what can go wrong when bureaucracies are beguiled by charismatic leaders.

Lisa Mckenzie, research fellow in sociology, London School of Economics

The housing crisis and welfare cuts have had expected and unexpected consequences. Although the rise in homelessness was not unexpected, the scale of it was. Emma Jackson’s Young Homeless People and Urban Space: Fixed in Mobility (Routledge) shows us the cruelty of allowing homelessness to return. It is cheeky of me to mention Mike Savage’s Social Class in the 21st Century (Pelican), but it is hard not to. This is a great read, and raises really important questions about class inequality. I was proud to be part of the research team involved in this project (looking at the precariat), along with Niall Cunningham, Fiona Devine, Sam Friedman, Daniel Laurison, Andrew Miles, Helene Snee and Paul Wakeling.

Richard Murphy, professor of practice in international political economy, City University London

Choosing two books of 2015 proved surprisingly easy. Both stood out for their courage. The first, most closely related to my work, is Paul Mason’s Postcapitalism: A Guide to Our Future (Farrar, Straus & Giroux). I am not an unequivocal fan of the book, but I am certainly a fan of why it was written and what it tries to do. The economic paradigm we live in is failing. Mason is appropriately seeking to find an alternative. The second is Steve Pottinger’s 2015 collection of poems more bees, bigger bonnets (Ignite). Pottinger is best known for his poem attacking Starbucks’ tax affairs. In this and other work, he seeks to do what poetry often does best, which is to give voice to dissent that demands change. Both books deliver hope. That’s enough for me.

Anna Notaro, senior lecturer in contemporary media theory, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, University of Dundee

Nicholas Mirzoeff’s How to See the World (Pelican) is a timely book. Less prescriptive than the title might suggest, it nevertheless contributes greatly to our understanding of the ways in which we create, communicate and interpret images. Only once we have learned how to see the world, Mirzoeff argues, can we engage critically and politically with the visual culture in which we live and become “visual activists”. Darran Anderson’s Imaginary Cities (Influx Press) (and its Twitter handle @Oniropolis) is a fantastic addition to the sprawling literature on cities, and a work of creative non-fiction that proves how the cities we live in are as fascinating as the cities we imagine. And there, perhaps, lies cities’ capacity to withstand agony in the face of past and recent tragedies.

Helga Nowotny, professor emeritus in social studies of science, ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich

For work: This Idea Must Die: Scientific Theories That Are Blocking Progress (Harper Perennial), edited by John Brockman. Delightful, irreverent and refreshing to observe brilliant scientific minds set about clearing the space of established knowledge of concepts they consider obsolete. This book attests to the provisional nature of all scientific knowledge, carried by the conviction that science continues to push us further into the territory of the yet unknown. For pleasure: Elena Ferrante’s The Story of the Lost Child (Europa Editions). I approached this highly acclaimed Neapolitan novel, the final of four, with some scepticism, but I was captured, like others before me, by the evocative language. Ferrante mixes a fictional reality with real history – a woman’s perspective on life that is brutally honest while at the same time admitting that life without illusion is not possible.

Olivette Otele, senior lecturer in history, Bath Spa University

Pernille Ipsen’s Daughters of the Trade: Atlantic Slavers and Interracial Marriage on the Gold Coast (University of Pennsylvania Press) is an outstanding piece of research about interracial marriages between Ga-speaking women and Danish traders and merchants who settled on the West Coast of Africa in the 17th century. This volume delves into the under-studied role of African women and their Euro-African children in the construction of the “Atlantic world”. Alain Mabanckou’s The Lights of Pointe-Noire (Serpent’s Tail) is a fascinating memoir that recounts the journey back to Pointe Noire in Congo by its author, an acclaimed novelist. It is about boisterous human interactions in working-class neighbourhoods, motherhood in a society that frowns on independent unmarried women, and the trajectory of a young intellectual. This is a beautiful and nostalgic exploration of self.

Fiona Peters, senior lecturer in English and cultural studies, Bath Spa University

The prolific “golden age” of crime fiction is often viewed as light-hearted and apolitical. My favourite “work” book of the year is Samantha Walton’s Guilty but Insane: Mind and Law in Golden Age Detective Fiction (Oxford Textual Perspectives), which offers a fascinating reworking of the era, utilising the lens of psychology to investigate issues of punishment and legality. Ruth Rendell’s posthumous novel Dark Corners (Hutchinson) is a novel I read for pleasure, tinged with a feeling of sadness that after this I would no longer feel the nip of anticipation at the arrival of a new Rendell or Vine. It did not disappoint and Rendell’s legacy is secure.

R. C. Richardson, emeritus professor of history, University of Winchester

Private letters and photographs, although locked in time and belonging to the circumstances in which they were first produced, have an afterlife as windows on to the past for the historian. Isaiah Berlin: Affirming: Letters 1975-1997 (Chatto & Windus), edited by Henry Hardy and Mark Pottle, and Louis Stettner: Penn Station, New York (Thames & Hudson), edited by Adam Gopnik, make an unusual, contrasting and absorbing pairing. The first brings together the vividly written, wide-ranging and penetrating correspondence of one of the great liberal humanist minds of the 20th century. The second assembles Stettner’s acutely observed and poetically presented impressions of personal moments in the public space of New York’s vast Penn State railway station of the late 1950s.

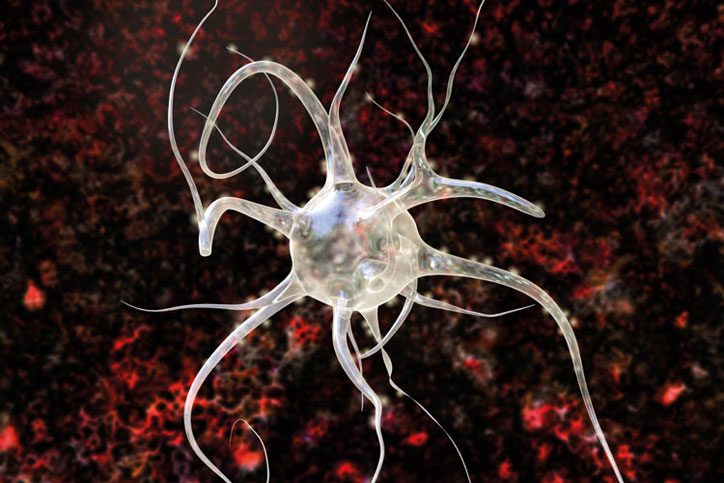

Georgina Rippon, chair of cognitive neuroimaging, Aston Brain Centre, Aston University

The Future of the Brain: Essays by the World’s Leading Neuroscientists (Princeton University Press), edited by Gary Marcus and Jeremy Freeman, is an awe-inspiring treasure trove of progress reports, frank opinions and exciting predictions from eminent neuroscientists of all genres. It covers a breathtaking range of technical and conceptual advances, from genomics to brain building via “neural dust”, BOINC and BAMS! In an era of hugely costly brain projects, reading this collection will allow you to share the concern behind the exhortation from one author to “beware the boondoggle”. Steve Silberman’s Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and How to Think Smarter about People Who Think Differently (Allen & Unwin) is an eminently readable and forensically detailed history of how the label “autism” emerged and evolved and its impact on the experiences of autistic individuals. Details of different “treatments” make for grim reading in places, but the progress towards acceptance of diversity makes for an optimistic ending. Written by an investigative reporter, this book successfully avoids the worst traps of “populist science” writing, and has recently won the Samuel Johnson Prize for non-fiction.

Elena Rodriguez-Falcon, professor of enterprise and engineering education, University of Sheffield

As an engineer and former basketball player who damaged her knees badly due to the friction between my trainers and the court, I was fascinated by The Science and Engineering of Sport Surfaces (Routledge), edited by Sharon Dixon, Paul Fleming, Iain James and Matt Carré. This book provides groundbreaking research and findings for everyone interested in sport surface science and its application. If you like a good thriller, Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train (Doubleday) is a must for a nice “relaxing” weekend. Hawkins’ intelligent plot managed to keep me reading non-stop. It is only towards the end that the story becomes a bit more transparent; nevertheless, it is a thoroughly enjoyable read.

Jennifer Rohn, principal research associate in nephrology, division of medicine, University College London

Novels about scientists (“lab lit”) are rare, and difficult to execute without getting bogged down in complexities or resorting to “boffin” stereotypes. Lily King’s Euphoria (Picador) does neither. Inspired loosely by the adventures of anthropologist Margaret Mead and her associates, it engagingly illuminates the reality of researchers: colourful, conflicted and all too fallible. If there were ever a character less like the typical mad scientist, it is Mark Whatney, protagonist of Andy Weir’s The Martian (Del Rey). Yes, he’s a total geek. But he is also foul-mouthed, streetwise and scathingly funny. See the film for the special effects, but read the book for an in-depth view into how real scientists think and work.

Flora Samuel, professor of architecture and the built environment, University of Reading

“How do you educate students for uncertainty?” This question has echoed in my mind ever since reading Helga Nowotny’s The Cunning of Uncertainty (Polity). The way forward, certainly, is to encourage both students and the public to critically engage with the creative assumptions behind scientific certainty – inspiring stuff. Edmund de Waal’s The White Road: A Pilgrimage of Sorts (Chatto & Windus) explores the history of porcelain, channelled through de Waal’s own embodied experience of making ceramics, with a particularly fascinating account of its early origins in China. This for me is in a similar vein to Nowotny’s book, but with its origins in the arts instead of the sciences.

Liz Saville Roberts, Plaid Cymru MP for Dwyfor Meirionnydd and shadow spokesperson for education

Brought up in London and educated in Aberystwyth where I learned Welsh, I now represent Dwyfor Meirionnydd as Plaid Cymru’s first female MP. Two books of poetry explain why I value weekdays in Westminster but belong in Gwynedd. Gerallt Lloyd Owen is among Wales’ greatest 20th-century poets and a master of strict metrical cynghanedd verse, and the posthumous collection Y Gân Olaf (Cyhoeddiadau Barddas) is a reminder of how he used a centuries-old discipline to goad the conscience of a nation. Imtiaz Dharker describes herself as a Scottish Muslim Calvinist who was born in Pakistan, adopted by India and married into Wales. I have chosen her most recent volume, the beautiful Over the Moon (Bloodaxe Books), because diversity is vital to our well-being.

Tara Shears, professor of physics, University of Liverpool

The best equations to describe the universe are succinct, far-reaching and beautiful. Frank Wilczek’s A Beautiful Question: Finding Nature’s Deep Design (Allen Lane) is a popular account of the importance and meaning of beauty in physics. The text is personal and informed, and I have really valued the unexpected, delightful insights it has given me. David Mitchell’s Slade House (Sceptre), on the other hand, is a book you should read with a sofa between you and the text. The rich, colourful stories have one common theme that will entrap you with delicious horror. It is impossible to put down – and should not ever be read late at night.

Natasha Slutskaya, lecturer in work and organisation studies, Brunel University London

Wendy Brown’s Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution (Zone Books) presents a carefully argued account of a world where economic demands become the only consideration for all conduct. For Brown, not only does the economisation of the society dictate the essential forms of subjectivity, it also dramatically weakens the very idea of a public. Rabih Alameddine’s novel An Unnecessary Woman (Corsair) is a captivating story about the attempts of an ageing and lonely woman, Aalia, to turn her world into a more tolerable place. Aalia’s memories of Beirut’s history are beautifully combined with reflections on literature, music and art.

Peter J. Smith, reader in Renaissance literature, Nottingham Trent University

Peter Kirwan’s Shakespeare and the Idea of Apocrypha (Cambridge University Press) is a meticulous and exciting challenge to the attribution fetishists. In trying to determine who wrote individual plays/scenes/lines, these literary sleuths prioritise an anachronistic, “post-Romantic” paradigm of authorship. For Kirwan, by contrast, attribution is “a transitory and changeable phenomenon”, historically contingent and mutable. The title of Clive James’ Sentenced to Life (Picador) encapsulates his mordant humour as his protracted lifespan surprises even him. This unflustered collection is infused with the wisdom and resignation of one dying: “these poems…are funeral songs/That have been taught to me by vanished time”.

David Toop, chair of audio culture and improvisation, University of the Arts London

Writing about sound is no easy matter, particularly in a second language. Daniela Cascella’s accomplishment in her second book, F. M. R. L.: Footnotes, Mirages, Refrains and Leftovers of Writing Sound (Zero Books), is to take the receptive reader far beyond sound, music and listening into the fragmented recesses of memory, the infinite subtlety of encounters with intangibility. Something similar could be said of László Krasznahorkai’s Seiobo There Below (New Directions). Through compellingly fractal sentences and forensic semi-fictional contemplation of makers, performers and artefacts, he asks unanswerable questions of what it is to instil a work of art with timeless profundity.

Salomé Voegelin, reader in sound arts, London College of Communication, University of the Arts London

George Home-Cook’s Theatre and Aural Attention: Stretching Ourselves (Palgrave Macmillan) is a must-read for students and academics of all things dramaturgical. It calls for an attention to the invisible and offers an earnest contribution to the quest for a listening beyond dialogue in the atmosphere of the performed. Poet and video artist Steve Roggenbuck’s new offering Live My Lief: Selected and New Poems 2008-2015 is published by Boost House, a publishing and performing co-op in Arizona that promotes “hopeful, critical, spiritual, activist orientations to the world”, and it does not just inspire reading and writing, but also urges you to get up and perform words about your own everyday.

David Wheeler, president, Cape Breton University, Canada

Guaranteed to irritate defenders of the status quo on both sides of the Atlantic, Ryan Craig’s College Disrupted: The Great Unbundling of Higher Education (St Martin’s Press) provides a compelling roadmap for the demise of entitlement in universities. For all its market-driven analysis, Craig’s prognosis ends in a technology-enhanced, less expensive and more democratic place. Jeremy Corbyn take note. Also on the theme of democracy and its perils, Robert Harris’ final volume in the Cicero trilogy, Dictator (Hutchinson), explains in novel form why this most brilliant of Roman politicians was decapitated in his prime. In the end it would seem he made far too many wickedly witty speeches for his own good.

Lord Willetts of Havant, visiting professor, Policy Institute, King’s College London, and former minister of state for universities and science

This has been the year of the rise of the robots. Martin Ford’s The Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of Mass Unemployment (Oneworld) is a valuable guide to how these technologies are actually developing. But it is much more than that. It is a bold challenge to the established view that technological change may disrupt patterns of work without reducing employment overall. Instead he argues that robotics and artificial intelligence is so radical that it will move as rapidly as humans can create new, unsatisfied wants. And he applies his argument to higher education in a chapter that will be of particular interest to Times Higher Education readers. If he is a pessimist, then Anne Tyler is sometimes criticised for being just a bit too homespun and humane – even optimistic in a melancholy kind of way. This underestimates her shrewdness and penetration. A Spool of Blue Thread (Vintage) reveals the characteristics of the modern family in a way that punctures our illusions without ever being cruel. It is about the stories we create to make sense of our lives – and is perhaps her farewell to the novel. We will miss her.

Joanna Williams, director of the Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Kent, and education editor at Spiked

I have spent much of this year thinking and writing about academic freedom. The contributors to The Case Against Academic Boycotts of Israel (Wayne State University Press), edited by Cary Nelson and Gabriel Noah Brahm, provide a superb rebuttal to campaigners wanting to isolate Israeli universities and scholars. They rescue the concept of academic freedom from those seeking to redefine it beyond all recognition. For something different I read Who’s Afraid of the Easter Rising? 1916-2016 (Zero Books), an inspiring exploration of the armed uprising against the British government in Dublin in 1916. James Heartfield and Kevin Rooney argue that the Easter Rising was the first crack in a growing revolt against the imperial barbarism of the First World War.

Duncan Wu, professor of English, Georgetown University

For anyone who enjoys the musical cadences of a writer with a style of impeccable elegance, or the incisiveness of an intelligence that could distinguish substance from superficiality at a hundred paces, The Spectacle of Skill: New and Selected Writings by Robert Hughes (Knopf), introduction by Adam Gopnik, must be the most rewarding book to be published in 2015. David Hare’s The Blue Touch Paper: A Memoir (Faber & Faber) is both funny and perceptive – not only about the perils of growing up in Bexhill-on-Sea, but also about the cost of a life in the theatre. It is the most compelling autobiography by any playwright since John Osborne’s A Better Class of Person.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login