Universities are finding themselves in the line of fire over the significant resources devoted to vice-chancellors’ pay. While the “mendacious” and “hysterical” media coverage has been dismissed by senior figures in the sector, it is symptomatic of an environment in which students, and taxpayers, increasingly want to know if university funds are well spent.

In a report published this week, the Reform thinktank assesses another area of significant university spending: widening participation. With more than £1 billion invested annually, its effectiveness is worth investigating. Perhaps more importantly, it is the key pillar in universities’ efforts to contribute to greater social mobility, a priority for both the secretary of state for education and the prime minister.

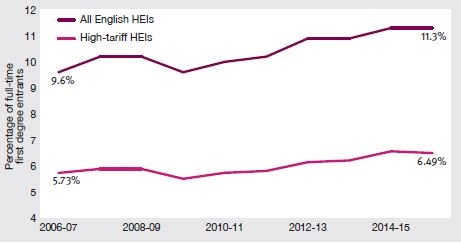

The most selective universities are the biggest spenders on widening participation, investing £194 per student more a year (on average) than their “lower-tariff” peers. They are also the ones struggling the most to diversify their intakes. In 2015, students from low-participation neighbourhoods made up only 6.5 per cent of the intake at the 29 highest-tariff English universities, a tiny increase from 5.7 per cent in 2006.

It is no news that “top” universities are not the most socially diverse, but given the levels of effort and money invested, the lack of progress is remarkable.

Proportional intake of disadvantaged students at English universities

Interviews for the report revealed that by far the biggest challenge, as perceived by high-tariff universities, lies in the low prior attainment of disadvantaged applicants. In 2015-16, less than 40 per cent of GCSE students in receipt of free school meals (a proxy for disadvantage) achieved five or more grades between A* and C, compared with 67 per cent of those who did not qualify for free lunches. At A level, you are less than half as likely to get three or more A grades if you are from a low-income background.

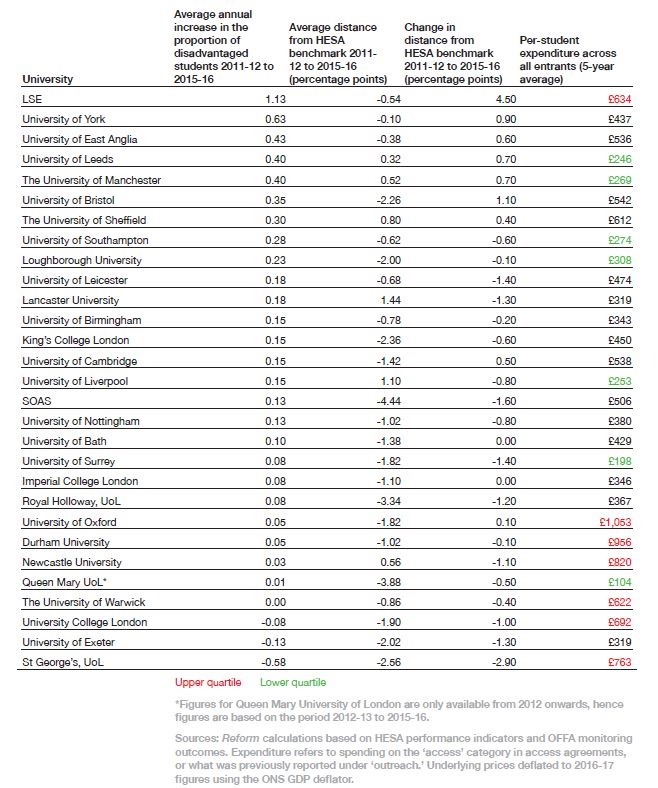

For the universities with the highest entry requirements, this places an immediate restriction on the number of disadvantaged students they can admit. We at Reform created access rankings for the most selective universities in England to find out whether any have overcome this obstacle and made significant strides towards admitting more students from disadvantaged backgrounds. This is what we found.

The rankings show that most of these universities have made very limited progress and consistently have an intake of disadvantaged students below the benchmarks set by the Higher Education Statistics Agency. The one outstanding exception is the London School of Economics, which made average annual improvements almost twice as big as the second-best performing institution, the University of York.

According to the LSE, this comes down to a number of factors, but the most significant change over the five-year period was a reform of the admissions system. LSE admissions are now fully centralised, conducted by professionals trained in spotting implicit bias, and automatically progress any viable applicants with at least two disadvantage “flags” to the second selection stage.

Such “contextualised admissions” have helped the prestigious university to increase the proportion of admitted students from low-participation neighbourhoods, from 3.1 per cent in 2011 to 7.1 per cent in 2015.

If all 29 highly selective universities replicated the performance in the LSE’s latest (and best) year, more than 3,500 additional disadvantaged students could gain access every year. Given the modest return on widening participation investments so far, universities should learn from any such efforts that seem effective.

While universities benefit from autonomy, and should continue to do so, they also have a responsibility to show fee-paying students, and the taxpayers subsidising loans, that funding is being spent to the best effect. Holding institutions to account for making real contributions to social mobility may be a better place to focus than how much their top executives are worth.

Emilie Sundorph is a researcher at Reform. Joining the elite: how top universities can enhance social mobility is available on the Reform website.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Social mobility: ‘elite’ universities should note LSE’s improvements

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login