My favourite placard at the London March for Science, and there were many strong contenders, said “Grab ’em by the data”.

I’m not exactly sure why it was my favourite, there were plenty of other pithy options. “Houston, we are the problem” for example; or “STEM the lies”. But it has something to do with how it managed to sum up many of the things that scientists were marching for in one fell swoop.

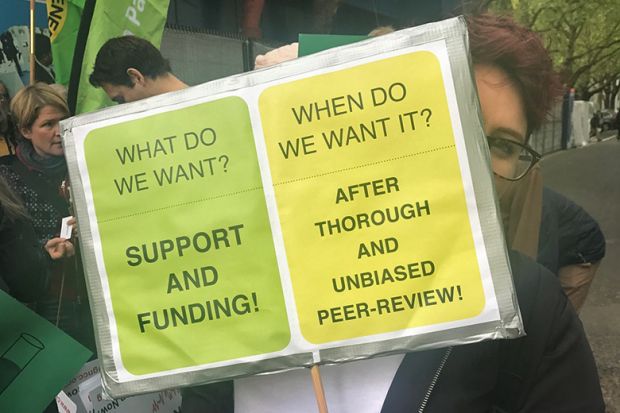

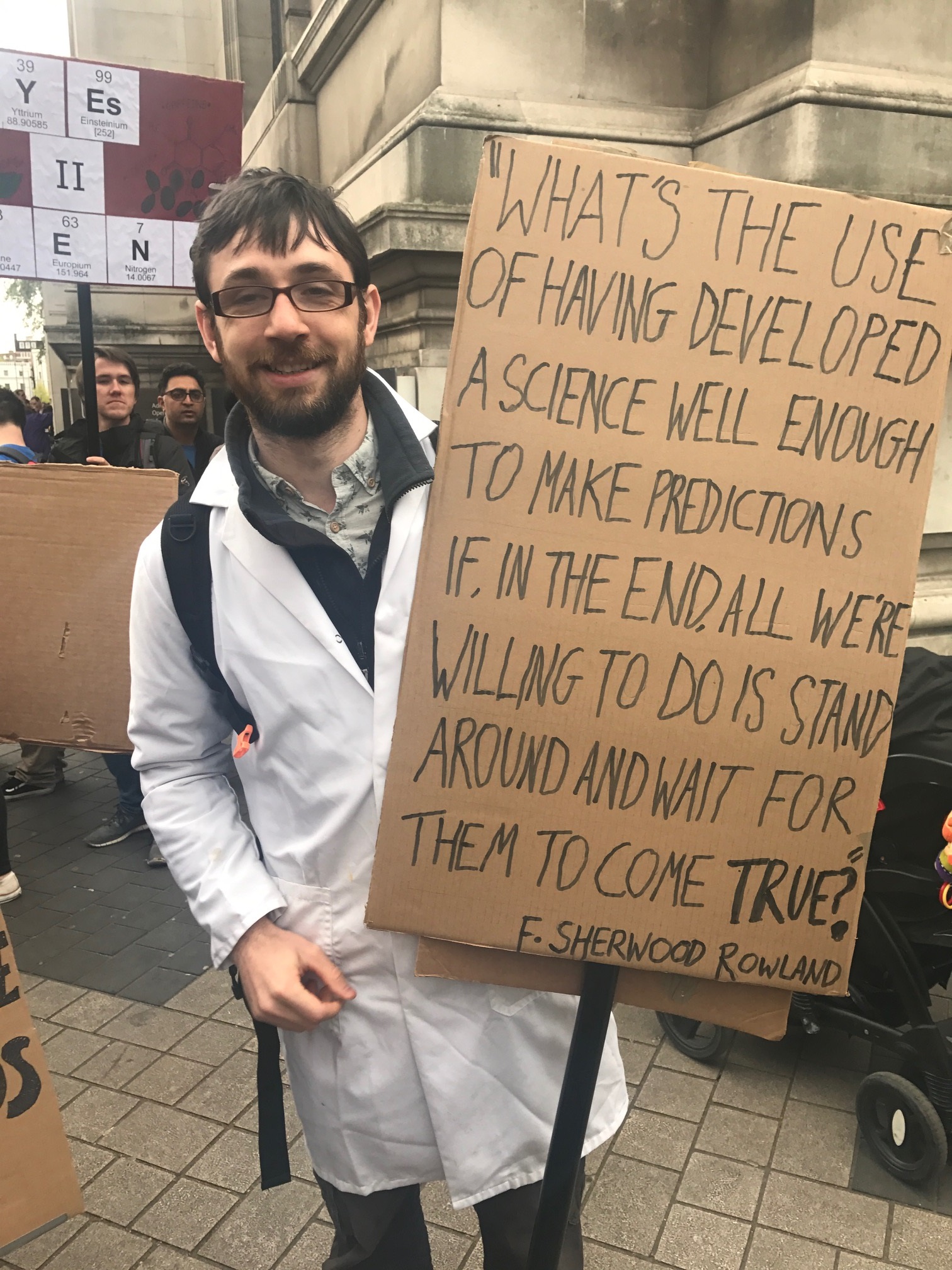

Those five short words seem to epitomise Donald Trump, disrespect for evidence, alternative facts and then throw in a bit of sexism for good measure. There were a lot of placards on the march and a lot of people. Organisers believe that somewhere between 7,500 and 10,000 people arrived at the march’s final destination, Parliament Square.

Search our database for science university jobs

The procession had carnival-like atmosphere with lots of people blowing whistles and groups randomly breaking out into loud cheers. There was a pink trombone playing When the Saints Go Marching In near the back and plenty of chants coming from the front. “Give me a particle, give me a wave” was my favourite one of those, in case you were wondering (the crowd shouted particle and then erupted into waves).

Those marching may not have been who you expect when you think about science – there were only a smattering of people wearing lab coats, for example. The marchers were predominantly young, some were not practising scientists and what struck me were the number of families pounding the pavements in the name of evidence-based policy.

Everyone was smiling and chatting, and onlookers stood by in awe of the parade of people as it snaked through the streets of the capital. London is just one of 600 marches worldwide planned for today. Across the world, march organisers hope that by bringing thousands of scientists together they can help to raise awareness of and defend the vital role that science plays in our lives.

But critics have been dubious about what the marches can achieve – and even whether marching is the best thing to do for science.

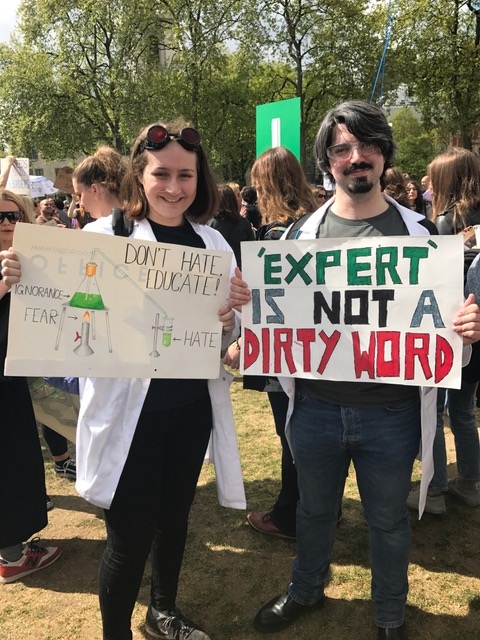

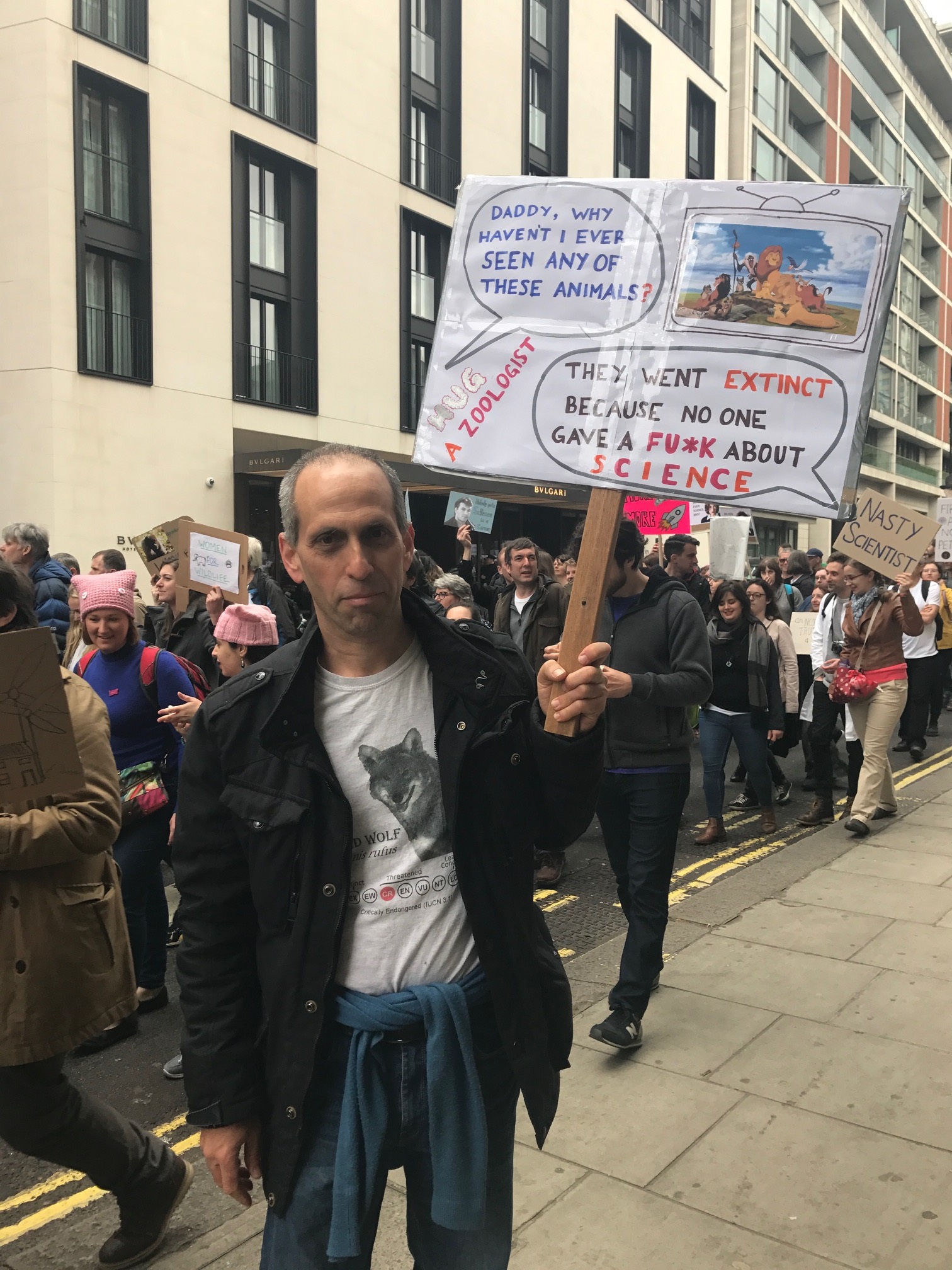

So I spoke to some of those who turned out in London to see why they had come along, and, of course, admire their placards.

Aaron Thierry, a climate activist from Sheffield who has a PhD in ecology, came down with a group of about 50 others from Sheffield to join the London march.

“I am very concerned about the way that science is currently being maligned and ignored by politicians across the world, particularly in the US. It feels like the world is going crazy and [we are] sticking our heads further and further in the sand by denying the realities that science is telling us about. If we don’t stop changing what we are doing, we are in for a really rough ride.”

Jessica Beck, a theatre director and lecturer in theatre arts at Canterbury Christ Church University, is originally from Pennsylvania and has been living in the UK for 13 years.

“If I was in the States I would be going to the [march] in [Washington] DC. I think the presence of all these people coming together saying ‘we believe in this’ will hopefully send a message to the politicians that it is important to prioritise science and education. To not value education or science and to turn education into a commodity, which is what is happening in Britain, is dangerous.”

Annette Fenner is the chief editor of Nature Reviews Urology. She spoke to Times Higher Education in a personal capacity and not a professional one.

“I am here to support scientists in the UK and worldwide who are suffering from the lack of funding, the lack of support from politicians and the public, poor media coverage and limitations to the dissemination of their research and to international collaborations. What scientists do is absolutely vital.”

Matthew Shannon, a PhD student at the University of Leeds, came to the march with Olivia Kent, a medical student from Queen’s University Belfast.

“[I came today because of] the whole sense of anti-intellectualism that is growing across the world, the alternative facts and the idea that ‘my ignorance is as good as your knowledge’. Even during Brexit you had people saying that we don’t need to listen to experts. I think that is a very dangerous route to go down, especially with climate change.”

Sir David King (right) is the foreign secretary’s special representative for climate change and was previously the government’s chief scientific adviser.

“People have forgotten that their very lifestyle depends on what science has delivered to them over the last 300 years. I am talking about penicillin, vaccines, aeroplanes, all the things that make our lives so comfortable, are taken for granted. At the same time, we are taking for granted the ecosystem and [ability of] the planet to deliver the air that we breathe. The problem is that we are not listening to the scientific community when they tell us uncomfortable truths. One of the uncomfortable truths is that climate change is driven by our use of fossil fuels and our deforestation of natural forests. We need to understand the capabilities that science gives us to manage these problems.”

Francisco Diego (left) is a teaching fellow at University College London.

“This is happening all over the world to raise awareness that there is a severe problem and we have to find the tools to understand the problem in order to tackle it. Science has the answer to that nothing else. We need to raise awareness, bring science and more of this understanding of the problems into the classroom for future generations because they will inherit this mess. We have to give them the tools to understand the problem and work out the solutions.”

James Walker is a PhD student at the University of Birmingham.

“I am quite an avid science communicator and I think this is a really good opportunity for people like me to come out and put a face on science. To say ‘I am a scientist, I do science, so can you’. It is really nice how diverse the crowd is.”

Anna Milan, a freelance copywriter, came to the march with her husband, Kieran Milan, and their two sons aged six and three.

“We’ve come as a family because we are concerned about the future of science and the environment that we are in, in terms of climate denial in the US, and with Brexit we are concerned about international cooperation. Really, we all came out to support evidence-based decision-making.”

Arik Kershenbaum is a Herchel Smith research fellow at the University of Cambridge.

“One of the nice things about this march is that it has no agenda other than showing support for science. I don’t see any conflict at all. What we are trying to say is not politically biased. Essentially we are all here to say people should recognise what we are doing and not dismiss and denigrate.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login