Mounting concern about exploitation is changing students’ understanding of what a doctorate is. Traditionally, PhD students have been seen as akin to apprentices, sacrificing higher pay for the opportunity to master a craft. Increasingly, however, there are moves to reconceptualise the doctorate as a job, to which equitable labour rights should apply.

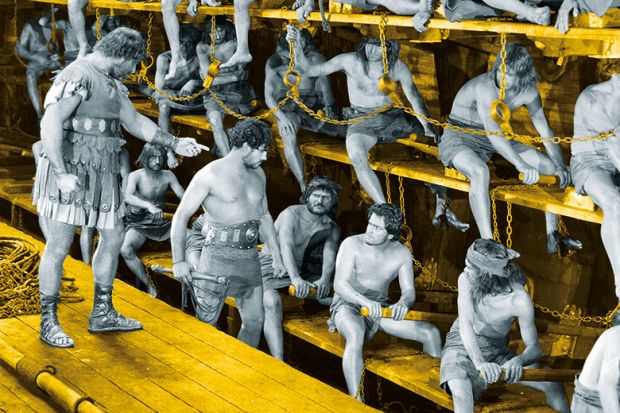

This position is clearly articulated in a recent article on the Tribune blog by Ansh Bhatnagar, a PhD researcher in theoretical physics at Durham University, titled “Postgrad researchers are the cheap labour of Britain’s universities”. In an important and well-articulated contribution to the debate, he highlights that seeing PhD students as the future of academia (apprentices) obscures the very real present value of their teaching labour, which receives minimal wage renumeration. He calls for this PhD teaching to be recognised through labour contracts.

Whereas 20 years ago, UK PhD students used to be encouraged to undertake small amounts of complementary teaching to gain valuable work experience, today they are expected to shoulder large amounts of marking and deliver numerous undergraduate seminars and tutorials. Many accept these responsibilities because the competitive job market incentivises demonstration of teaching experience on CVs and because increasing tuition fees and spiralling living costs are making additional earning a necessity – especially for international and self-financing students but increasingly also for those on fixed stipends.

PhD students’ calls for their work to be recognised as academic labour are being (inadvertently) reinforced by supervisors and mental-health initiatives that encourage them to see their work as a “job”, with regular working hours (to combat poor mental health).

While sympathetic to all these pressures, I caution that such thinking is both symptomatic of and instrumental in the neoliberalisation of higher education. It jeopardises investment in the academic self that lies at the heart of the PhD process.

Student teaching can be mutually beneficial for institutions and PhD students. The problem arises when PhD labour becomes integral, not additional, to teaching delivery. When departments struggle to deliver their required teaching without PhD labour, the institution, rather than the PhD student, becomes the primary beneficiary.

Teaching experience that is about delivering teaching rather than learning how to teach differs little from “on-the-job training” – common in other professions and postdoctoral positions. It may also change the type of teaching undertaken, for while shadowing experienced academics (often called “demonstrating”) offers high pedagogical value, it offers little immediate institutional gain. In contrast, large volumes of repetitive small-group teaching and marking offer large institutional benefits with diminishing pedagogical value.

When the emphasis regarding teaching shifts from learning to delivery, the PhD student is no longer an apprentice, and paying apprentice-level rates of pay undeniably becomes exploitative. However, seeking labour rights for PhD students elevates the institutional value of delivery above the pedagogical value of learning even further. It encourages departments to see their PhD cohorts as a transient, ready supply of teaching labour to meet the pressures imposed by increasing student numbers rather than as an apprentice academic community to invest in – which, longer term, encourages retention.

It is precisely the escape from workplace-style labour demands that allows for investment in the academic self during a PhD. Experienced academics offer an analytical clarity that comes from their depth of expertise and breadth of contextual understanding of their research in social and political terms. These characteristics are built during the PhD years. It is a formative period that establishes intellectual freedom and the habit of reading widely and deeply, fostering the lengthy and deeply reflexive work of figuring out who you are as a researcher – the results of which drive whole academic careers.

It is these characteristics that mark out academics, providing foundations for their teaching as well as their intellectual nourishment of students, fellow academics and the wider world. As such, preserving the PhD as a space for learning and self-investment is vital to the future of academia. And while it won’t address the financial pressures they face, the solution to PhD students’ exploitation is not to view the doctorate in labour terms but to adequately staff higher education to meet teaching demands – a responsibility that universities and the UK government need to recognise.

Of course, the traditional apprentice model has its own problems, including instances of disrespect, exploitation and infantilisation. But re-expressing the master-apprentice relation in neoliberal terms will only encourage PhD students to see themselves as delivery agents rather than owners of their own intellectual capital.

Such internalisation and individualisation of neoliberal rationalities will only accelerate the corporatisation of higher education. It will create an academia that risks losing its craft.

Ruth Machen is a research fellow in the School of Architecture, Planning and Landscape at Newcastle University.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login