Many years ago, when I was working at the University of East Anglia, I came across a Reclaim the Streets protest on Unthank Road. They caused a bit of traffic chaos doing a slow walk into the city, but most memorable was the protester holding a sign reading “Stop Badness”. Well, quite. If only we could. But there is so much badness, everywhere in the world, it’s hard to know where to start.

I joined the University and College Union (UCU) as a means of stopping badness, or at least to give myself a fighting chance. The higher education sector is, to put it mildly, in a state of frayed disarray. Caught between a predatory government, marketisation and overregulation, sometimes it’s hard to know how any teaching happens at all. The pressures are chaotic and confusing, and the UCU fought a good fight over pensions with employers who, year by year, seem to be becoming bad versions of the good leaders we so desperately need. But, like a lot of things post-pandemic, the UCU itself has suddenly been fouled by its own miasma of badness, and the recent motion pushed by the Stop the War Coalition, which passed at congress last week, was, to use a bad metaphor, the final straw that provoked me into cancelling my membership.

It wasn’t so much the infantilised language of the resolution – yes, we can all agree that war mostly affects the poor and disenfranchised – but the dark stink of hard-left ideology that manages to connect Zelensky’s Jewishness to Nato and tries to pretend there is some kind of moral equivalence between Russia and Ukraine. It’s a conference resolution written by Twitter extremists, oiled with intransigence and bad faith, and containing language that revels in its own obtuseness. It’s insulting to friends and colleagues who are experiencing first hand Russia’s unprovoked war of aggression and represents a takeover of congress by fringe elements of the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) who, rather than wanting to stop badness, have some bad intentions of their own – namely, to bring about the collapse of capitalism and the suppression of democracy.

In part this is a consequence of the manipulation of the processes of congress. Out of 120,000 UCU members, only around 300 attend congress. Exhausted from the chalkface, only the most hardcore contingent is going to sit through a long bank holiday weekend in a stuffy conference centre. This gives ample room for UCU Left – the entry-level SWP movement, who are well organised and militant – to set and execute the agenda.

As Simone Weil pointed out in her essay On the Abolition of All Political Parties, totalitarianism is the original sin of the political party. Extremists on both sides, she wrote, might be “struck by a sort of mental vertigo on discovering that they were in complete agreement on all issues”.

Essentially, when the right and the left travel to their extremes, they meet each other on the way round. Weil wrote the essay as a letter to de Gaulle to articulate what she saw as the dangerous polarisation of French politics in the 1930s, which allowed for the Nazi occupation. What she describes has a chilling resonance for our similarly polarised politics. “Instead of thinking, one merely takes sides: for or against. Such a choice replaces the activity of the mind,” she wrote.

That this contamination has taken over the UCU is now quite a big problem, especially for an organisation that claims to represent the UK’s intellectual labourers. The union is in danger of becoming a political party of its own, while the leadership seems to spend too much time showboating on social media instead of reining in some of its bad actors.

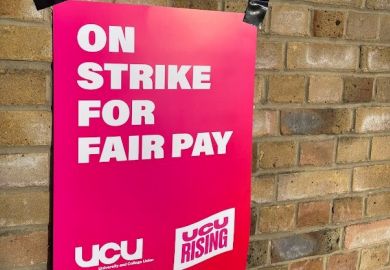

And the strikes – we’re all frankly fed up with them. That is not to say we shouldn’t strike for issues that matter to the entire sector, but the recent industrial action feels pointless and increasingly driven by the militant minority.

As well as political polarisation, we’re dealing with institutional atomisation. While too many students might be an issue for one university, in another it’s not having enough. The current marking boycott is causing chaos and, in some cases, punitive responses from individual institutions. And the only people who really suffer – apart from the academics who will have to do the marking anyway, sooner or later – are the students. There must be a better, more discursive way forward for individual institutions to have the support they need to deal with the particularities of their specific conditions. What happens at Birkbeck is not happening at Queen Mary, and targeted action – supported by the UCU – would have been helpful in navigating our recent moment of crisis. Across the sector what’s needed is not more picket lines, but more thoughtful engagement and lobbying about what a realistic future might look like for the broken model of higher education in the UK.

That feeling of being politically homeless has been with me for a while; to whom do I turn to represent and protect the classroom?

On one side I have managers who have drifted ever closer to the right, embedded with their draconian political masters, and on the other the radical left, who want to burn it all down. In between is an increasingly narrow ledge where it’s still possible to do what Weil believed teaching could do best – encourage deep thought and deep listening that develops the mind, that makes it possible to become the kind of citizen who knows how to think critically rather than reactively about the world and who knows how to tell the difference between the good and the badness.

Julia Bell is a reader in creative writing at Birkbeck, University of London.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login