Forecasters regularly predict that innovations in information technology will continue to expand distance learning courses, offering students greater choice about how and where they learn. However, current downward trends in UK and Australian distance learning degree enrolments suggest that we are in a distance delivery dilemma. But do the falls in student numbers indicate that international students have lost their appetite for distance learning?

The UK position

Total international enrolments to UK distance learning degrees, including online, fell by 5 per cent over the past five years, and this at the same time that many universities had sought to expand provision.

Data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency show that there were 118,000 international enrolments to UK distance degree programmes in 2017-18. When you take out figures from the two universities that have established strong new in-country partnerships, the decline would have been 12 per cent.

Information on subjects and levels of study is not collected routinely, but previous studies suggest that more than 50 per cent of international enrolments were for business and finance-related courses, with nearly 60 per cent of distance learning students pursuing master’s degrees.

Any decline is of great concern, both financially and academically, particularly as the UK government, and many institutions, had viewed distance learning degrees as a means to expand education exports into new markets.

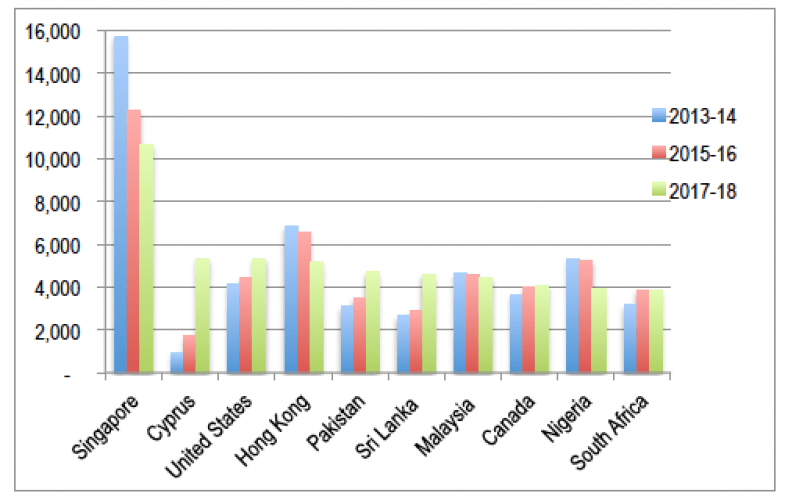

The lead countries for UK distance learning degree enrolments (Figure 1) all have historic ties to Britain. Although Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia and Nigeria have experienced declines, the others have expanded.

This ranking contrasts with direct recruitment to the UK, where China, India, Germany, France, Italy and Spain are among the top 10 student source countries.

Figure 1: Lead countries for UK distance learning enrolments (Hesa)

A question of distribution

Data for international distance learning enrolments are limited, but review suggests that perhaps 400,000 students follow English-medium degree programmes globally.

While Australian enrolments have declined (currently 7,390), for the US there has been approximately 5 per cent per annum growth to 42,600 to autumn 2016. Compared with the UK’s totals, these figures appear relatively modest, even allowing for differences in data collection.

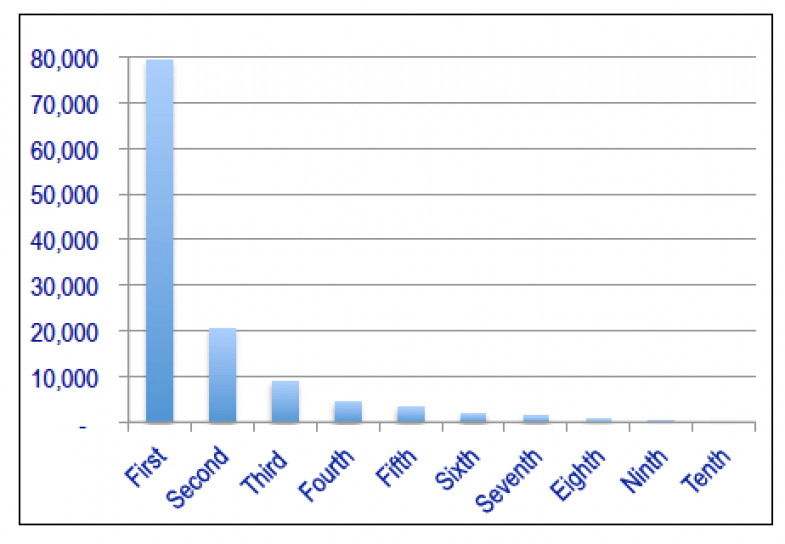

Is there an optimum level of operation for academic and financial benefit? The UK pattern is revealing: 80 per cent of distance learning students were enrolled in just 10 per cent of providers, while one-third of providers enrolled fewer than 100 students each (Figure 2).

The University of London accounts for a third of enrolments in the UK, but even discounting these, the distribution remains skewed. While the detailed picture will be more nuanced, this pattern suggests that many institutions might be struggling to achieve viable numbers, and thus probably not covering costs. Similar distributions are evident in Australia and the US.

Figure 2: Distribution of enrolments to UK distance learning programmes according to the number of institutions by enrolment decile (Hesa).

Meanwhile, there have been more than 100 million registrations to once-hyped massive open online course (Mooc) programmes. While this is a great success, the rate of increase is slowing and completion rates remain low, about 3 per cent.

Nearly 50 Mooc-based degrees are offered globally, but enrolments average a modest 10,000, and the Georgia Institute of Technology’s master’s programme in computing accounts for 60 per cent of these degrees. Even in Georgia Tech’s case, the proportion of international enrolments is likely to be low.

Some challenges

Globally, the estimated 400,000 enrolments would seem modest by comparison with internationally mobile students (more than 25 million by some accounts), but are there opportunities for growth?

Despite a downturn in enrolments, distance learning is not likely to go anywhere and will continue to evolve in a role that sits alongside or is integrated into the traditional campus.

And optimism for the approach remains strong, with the original reasoning behind it still holding good: it offers more choice for students; the flexible delivery fits around employment and family commitments; it gives greater opportunities for the disadvantaged and those facing discrimination; it improves access for small states with limited resources; and it makes progress towards bridging the gap between supply and demand for education.

In the midst of falling numbers in the UK, some institutions have expanded their distance learning offering by adopting different approaches, such as the University of Edinburgh’s suite of online master’s degrees or the universities of Salford and South Wales’ successful European partnerships. In the short term, UK distance learning enrolments might experience small declines as universities move to rationalise, driven particularly by financial concerns.

Meanwhile, US institutions appear well positioned for international growth because they already offer many distance learning programmes for domestic students and are at the forefront of Mooc development. This positioning offers a stepping stone towards international expansion.

But challenges remain, including a lack of official recognition of foreign degrees; degree mills undermining the reputation of foreign providers; tuition fees that are often higher than those at local universities; and domestic demand being met through new in-country institutions.

A starting point for any institution is to have clear objectives that are integrated within an overall international strategy. Long-term investment is essential (think 10 years), as is establishing priority markets and building appropriate programmes and delivery means. Growing niche topics and seeking professional recognition is also needed. But most essential is persistence and patience.

Neil Kemp is an international higher education consultant and board member of the Council for Education in the Commonwealth. He was previously director of education UK at the British Council as well as the organisation’s director in a number of countries.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login