The Web of Science’s recent decision to delist two journals published by the Switzerland-based open access publisher MDPI, among dozens of others, follows the appearance of a list of more than 400 allegedly predatory MDPI journals on the predatoryreports.org website several weeks earlier.

While some welcomed Predatory Reports’ move, I did not. As someone who has studied so-called predatory publishing for almost a decade, I believe that creating such lists doesn’t promote integrity or trust in science. Likewise, it will not solve a key reason for the creation of journals of questionable quality: the pressure on academics to produce more and more papers.

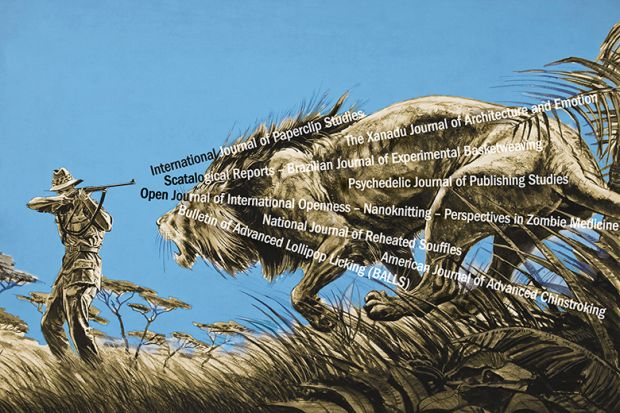

The discussion of predatory journals began more than a decade ago, when University of Colorado Denver librarian Jeffrey Beall created the first list of predatory journals (and publishers), defining them as outlets that dupe scholars to publish in them and do not follow basic publishing standards, such as conducting peer review.

But when discussing predatory journals, let us not reduce this phenomenon to “publishing fake results” or “providing low-quality peer review”. Such phenomena also happen in journals published by the most prestigious publishing houses. What the concept of predatory journals actually reveals is the deep inequalities between the scientific working conditions in countries close to the “centre” of global science, such as the UK and US, and those on its periphery.

All lists of predatory journals have concentrated almost entirely on English-language journals published in non-English-speaking countries. As a result, their usefulness is limited because although many science policy instruments promote English publications, the lion’s share of researchers still publish in their local languages.

Moreover, many researchers in semi-peripheral regions publish in journals listed as predatory precisely because national science policies recognise them. For example, in Poland, my own country, several MDPI journals are highly regarded in the national research evaluation exercise of higher education institutions. Therefore, for many researchers, publishing in MDPI journals is a smart decision because these publications “count” towards their workplace’s goals and might receive recognition and rewards. For deans or rectors, promoting publishing in such outlets may also be profitable because research evaluation scores are essential to their careers.

Papers published in predatory journals are also cited by prestigious journals. When our research group examined the citations of papers published in predatory journals, we discovered that they were not criticised more frequently than papers from other journals. More importantly, we found that these papers were often cited because they were the sole data sources on various semi-peripheral countries and their contexts.

Two commonly suggested solutions for addressing predatory publishing are increasing awareness among scholars about journal quality and promoting a “quality over quantity” culture. However, these approaches overlook the fact that national-level regulations or institutional policies in peripheral countries may drive publishing in predatory journals. And after a decade of working with policymakers from semi-peripheral countries, I'm not optimistic that a greater awareness of quality will spread to them.

That is particularly true because at least some predatory journals continue to be indexed by the likes of the Web of Science and Scopus – and some have high impact factors. This legitimacy is absolutely essential: without it, there would not be so many such predatory journals. In that sense, you could even say that these well-known bibliographic databases co-produce these journals.

The best solution to predatory publishing would be to reduce the global pressure to publish more and more papers, but this is a long-term goal. If we want solutions for the present moment, let us focus on creating more reliable registries of scientific journals in multiple languages that adhere to basic publishing standards. The European Reference Index for the Humanities and Social Sciences would be a good place to begin an effort to create geopolitically sensitive whitelists.

It’s also crucial to reconsider the language we use to describe predatory journals, to avoid condemning scholars who publish in them or accusing their publishers of bad intentions. Our group proposes that a journal be instead described as a “mislocated centre of scholarly communication” when it is invisible or perceived as predatory by institutions at the centre of the academic world but is regarded as prestigious by peripheral institutions (often because it presents itself as international – although sometimes in the sense of regional, rather than entirely global in the Western sense).

Many peripheral scholars publish in these mislocated centres of scholarly communication or actively participate in their creation. But this is not a reflection of their integrity or the quality of their work. Rather, it is an unfortunate result of the current, geopolitically divided state of academia.

Emanuel Kulczycki is professor of scholarly communication and head of the Scholarly Communication Research Group at Adam Mickiewicz University, Poznań, Poland.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login