In August, the US government gave federal agencies until 2025 to make all research that they fund immediately open access.

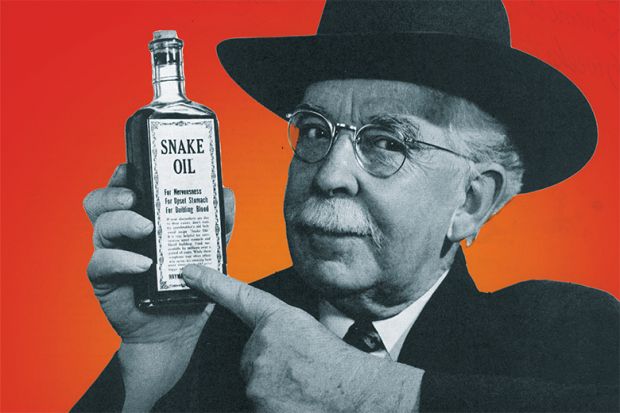

I fully endorse the principle that publicly funded research should be freely available to everyone. But my recent experiences with open access “publishers” suggest we should take great care with how the mandate is implemented in practice.

I first became aware of so-called predatory publishers through their incessant email spamming despite oft-repeated requests to unsubscribe me. But after a paper of mine was rejected by several more mainstream journals, I decided to conduct a controlled experiment with the spammers.

I chose three similarly named journals, all of which promise rapid turnaround. Two commit to a publishing decision within two weeks, the third within seven days (for an additional $50) on top of the $100 publication fee (and $30 for the corresponding monthly or bimonthly print edition). Given how other journals operate, we might think that peer review is impossible in such time frames, but the myth-busting section of one of the publishers’ websites assures authors that “a journals [sic] access policy…does not determine its peer review policy”.

Incidentally, that grammatical error is not an isolated slip: the communications of all three journals, despite their published US addresses, were marked by poor English and a general lack of clarity – as well as a repeated emphasis on speed and, especially, payment.

The first to respond, supposedly based in Oregon, focuses on “theoretical and empirical research in the broader fields of Arts and Humanities areas”. Six weeks after submission, I received two identical acceptance emails announcing that “the reviewers have recommended your paper for publication, subject to minor revisions”.

The “reviews” and suggested “minor revisions” made no sense. Nor did they demonstrate any familiarity with what I submitted. “I suggest the author to revised the introduction section a bit to develop the motivation and the flow of the discussion,” [sic] one wrote. Irrelevant to my essay, the boilerplate review states that the introduction “should present…background and the idea of the study [including 7-8 citations]…then present the brief of methodology, then present the main findings briefly.”

I asked the editor for clarification. After merely repeating the comments without elaboration, he added that they are “a checklist” – therefore, not a peer review. “Congratulations!” he repeated. I withdrew my manuscript.

The editor of the second journal to respond, apparently based in Louisville, Kentucky, wrote (four weeks after submission), “Your research problem is of interest to us. Your manuscript has been reviewed by two reviewers. Please find the reviewers’ comments and suggestions as attached with this letter. The editorial board has decided to publish your paper with no modification.”

No reviews were attached. There were only two tiny tables of “evaluation criteria” – “original contribution”, “well organized”, “author guidelines followed”, “based on sound methodology” and “analysis and findings support objectives of paper”. I scored all “yeses”. The “comments and suggestions” section read, “This paper will undoubtedly contribute to the existing field of research. This is a timely research. The paper is organized, especially in presenting the consistent thoughts.”

There is no evidence that a human being, let alone a qualified scholar, ever read one word of my paper. Much of the editor’s letter was devoted to instructing me how to send the $200 payment to a person in Bangladesh, where the journal’s “financial unit” is located. “Please inform the editor after making payment of the publication fee,” it urged.

The final journal, claiming to be based in Washington, DC, accepted my submission after seven days. Its context- and content-less reviews almost perfectly mirrored those of the other two journals. A sample: “I appreciate the author to choose the type of topic for study. The paper is properly organized and demands appreciation. Representing the dedication and knowledge of the researcher about the topic and skill in research.” [sic]

Payment was again to be made to a person in Bangladesh with the same surname (but a different first name) as the person from the previous journal. But since this one only demanded $100, I paid – in order to continue my experiment.

In less than a week, I received a Word file – not page proofs – for final review. It was a mess, especially regarding spacing, paragraphs and references. No reader had caught a few missing words. Indeed, I seriously doubt that anyone had read it at all.

Despite my request to be kept informed, I only found out my paper had been published when I checked randomly three days later. I have no idea when the print issue, for which I had to prepay, will arrive – if ever.

While my sample size of predatory publishers may be small, all data points agree. This is no more than pseudo-scholarly publishing for sale, feeding off the increased pressures on academics around the world to publish.

I know that open access is better established in the sciences and that there are many perfectly respectable open-access journals that embrace traditional scholarly standards. But studies suggest that even well-established researchers are sometimes duped.

While editorial standards seem to be slipping across the board, they will slide much further and faster unless open access mandates come with a way of distinguishing outlets that at least aspire to deliver a scholarly standard and service from the pure grifters.

Harvey J. Graff is professor emeritus of English and history at The Ohio State University and inaugural Ohio Eminent Scholar in Literacy Studies.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login