It may or may not have been Abraham Lincoln who first noted that a leader can’t please all of the people all of the time, but never did the observation appear more apposite than during the past 18 months.

The handling of the pandemic in almost every country in the world has come in for heavy criticism from multiple angles. Some national responses were widely deemed too late or light-touch, while others were condemned as excessively cautious, authoritarian or economically ruinous. But whatever your views, another thought has no doubt echoed in the minds of many observers: “I’m glad it’s not me who has to make the decisions.”

The same might be said within universities. University leaders may not have been presiding over the liberties of millions of people and the prosperity of entire nations, and some may have had little room for manoeuvre around national policies and sector regulations. However, their direction on issues such as whether to lay off staff or to ask them to take pay cuts, not to mention when to reopen physical teaching, had a level of consequence that the day-to-day administration of universities rarely does.

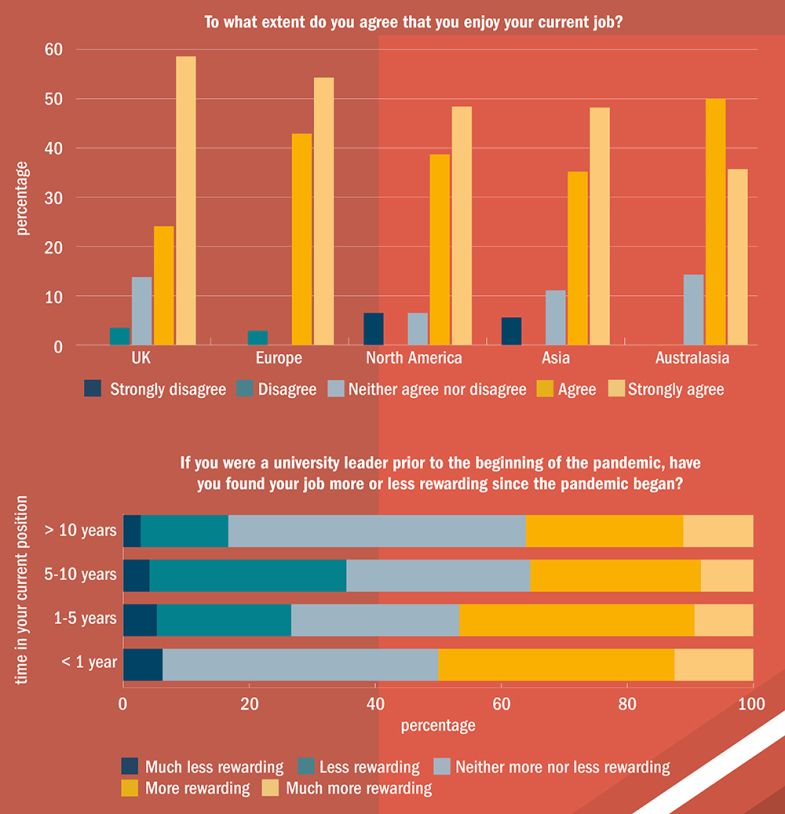

Yet whatever burdens such heavy and urgent responsibility may have imposed, it does not appear to have diminished university leaders’ appetite for the job. Indeed, of the 180 university leaders recently surveyed by Times Higher Education, many more (42 per cent) have found their job to be more rewarding during the pandemic, rather than less (26 per cent).

This is one of the more striking findings of the survey, carried out between 25 June and 4 August among the leaders of universities ranked in at least one of THE’s rankings. The survey attracted responses from 55 countries, spread across six continents.

Another eye-catching finding is that the online teaching experience hasn’t, in leaders’ view, hastened the demise of the physical lecture or significantly increased the threat to traditional universities from digital disruptors. And whatever the financial ravages of the pandemic and the political fractiousness of universities’ operating environments, positivity about institutional futures abounds. Clearly, university leaders are a resilient bunch.

Leaders across the world express strong enjoyment of their jobs. Overall, 88 per cent agree that they enjoy their current jobs, with well over half of those strongly agreeing. Only 4 per cent disagree, 3 per cent strongly. Overall positive sentiment is highest in continental Europe (which, for the purposes of the analysis, excluded the UK) and Australasia; it is lowest in Asia – but even there, 83 per cent enjoy their jobs, against just 6 per cent who do not.

For statistical reasons, responses from Africa and South America have not been analysed at a continental level. However, positivity is evident in the answers from those regions, too. For instance, Barnabas Nawangwe, vice-chancellor of Uganda’s Makerere University, sees university leadership as “an opportunity for me to be at the centre of my country’s development agenda”.

Leaders new to their jobs are especially enthusiastic, with 95 per cent of those in their current role for less than one year enjoying their jobs and no one strongly disagreeing. THE’s analysis also reveals that the leaders who enjoy their jobs the most are most likely to say that they found them more rewarding during the pandemic.

So are university leaders just gluttons for punishment? Not according to Dawn Freshwater, vice-chancellor of the University of Auckland. She appreciated the more streamlined way in which decisions could be made during the pandemic. Noting that complaints about university bureaucracy are typically levelled at managers, she says: “But we don’t like bureaucracy either, so we were very happy to lose some of that through the pandemic and actually be able to clear some of the clutter out of the daily grind. So the change that was required anyway has been accelerated, and that does make the job more rewarding.”

That sentiment is echoed by Mamokgethi Phakeng, vice-chancellor of the University of Cape Town. “Because people didn’t know what is next, there was a sense of ‘give us direction as a leader’.” Normally, the leader gives direction and there is pushback. We negotiated a new strategy with the labour unions. They asked a few questions and then said yes. I didn’t expect it to be that smooth.”

Freshwater also cites the pleasure of seeing the crucial role of research in slowing the virus’ spread and developing vaccines. “There is enormous reward through seeing how important our research has been in this context and the way it has been recognised through the rehabilitation of evidence-based decision-making by governments.”

Rocky Tuan, president and vice-chancellor of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, notes that the pandemic has been an especially fraught period for his highly international institution. Still, while there is “no denying that the impact of the pandemic is terrible, it also motivates us to do things differently and spur innovation. For example, the new pedagogies that have been developed are not mere second-best options, but are novel practices that broaden our horizons in ways we have never imagined before.”

However, Patrick Deane, principal and vice-chancellor of Queen’s University in Canada, notes that leaders’ enjoyment of the job may be about to take a turn for the worse. “In Canada, we are trying to come out of the pandemic but things are kicking in that make the job a whole lot less satisfying, such as the understandable fear in some constituencies of a return to campus. There are also labour issues and pent up expectations that are hard to address.”

And several leaders dispute the idea that they “enjoyed” the challenge of the pandemic. For Bob Brown, president of Boston University, “leadership is a very human-oriented undertaking. After so many months without being with people, ‘enjoy’ is not a word I would use at all. ‘Rewarding’, yes, because you feel the institution needs leadership now probably more than it has during my time.”

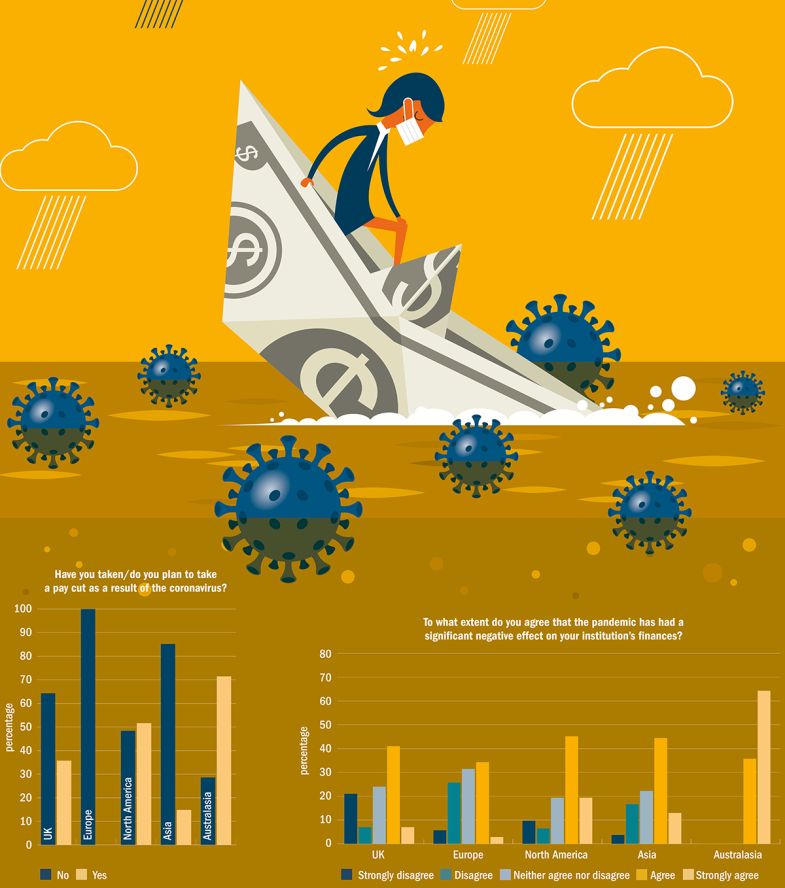

It is certainly clear that the pandemic has given universities and their leaders a lot of challenges to overcome. Among the survey respondents, 58 per cent agree that it has had a negative effect on their institution’s finances, rising to 100 per cent among the 14 respondents from Australia and New Zealand, two-thirds of them strongly agreeing.

Asked which income streams have been most affected, Australasian leaders overwhelmingly cite international tuition fees. According to Michael Scott, vice-chancellor of the University of Sydney, this is because international fees have become such a big money-spinner, but Australia and New Zealand’s closed borders have made it virtually impossible for international students to come to the region.

“This year, Sydney’s international student numbers have held up quite well, as they have at the other sandstone institutions, but many of the smaller, regional institutions have lost out and may struggle to see how that market will come back,” he says.

Nor is the pain necessarily over even as vaccination offers the prospect of more open borders. Another Australian vice-chancellor fears that the financial impact of the pandemic “is likely to continue for several years and to be at its worst in 2022-23”.

Another issue in Australia is that the commonwealth government “went out of its way not to provide ongoing, sustainable support during Covid”, according to Scott, excluding universities, for example, from its JobKeeper employment subsidy scheme. “The prevailing narrative from government was that universities were wealthy and should be able to deal with the challenge.”

Concern about the financial impact of the pandemic is lowest in continental Europe, which has a much less commercialised university sector than many other regions. “We are a state-financed university with a fixed budget,” notes Joachim Hornegger, president of the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, while Daniel Crespo, rector of Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, says that “the Spanish and regional governments took care of the economic effects of the pandemic, so there was no significant [financial] impact”. Where there were financial hits in Europe, international fees and research grants and contracts from corporate or charitable bodies were the most significant areas.

International fees are also UK vice-chancellors’ biggest financial headache, but by a much smaller margin than in Australia, reflecting the country’s less restrictive border policy. Leaders in North America and Asia are most exercised by tuition fees and government grants associated with domestic students.

For Tanweer Hasan, vice-chancellor of the Independent University of Bangladesh, particular strain has been caused by the need to offer financial aid to students to compensate for job losses and reduced incomes. Several leaders also mention the loss of income from residences as lockdowns confined students to their family homes.

“We lost about two-thirds of our residence and catering income because we took a moral rather than contractual view of our relationship with our students and stakeholders, but we managed to make balancing savings elsewhere,” says a UK vice-chancellor.

Australasia’s travails with international education are also reflected in its reaction to the pandemic. Across the world, 15 per cent of respondents say they have made or will make some permanent staff redundant as a result of the pandemic. That figure is similar across all analysed continents except Australasia, where 86 per cent of respondents plan to make or have made redundancies – though all say the redundancies account for less than 10 per cent of the staff body. An analysis of Australian Bureau of Statistics data suggests that Australian universities laid off about 35,000 staff in the 12 months to May. But these figures do not include the large numbers of casual and fixed-term staff whose contracts have not been renewed. Universities Australia has estimated that 17,000 lost their employment in 2020, while other estimates put the figure at more than double that.

Globally, just 2 per cent of respondents have made or envisage making more than 20 per cent of their permanent staff redundant.

Many university staff have also been asked to take a pay cut. This was a common reaction by leaders at the start of the pandemic, in particular, before any support schemes had been organised by governments. In a similar survey of 200 university leaders that THE carried out between 30 April and 22 May 2020, 12 per cent of respondents were planning to ask staff to take pay cuts, with another 20 per cent undecided at that point.

Of course, it is politically difficult for a leader to ask staff to take pay cuts if they don’t take one themselves. In THE’s latest survey, 26 per cent of respondents say they have taken a cut, compared with 24 per cent in 2020 (when another 22 per cent were undecided). Just 6 per cent of those have taken cuts of more than 20 per cent, with 32 per cent taking between 10 and 20 and 18 per cent between 5 and 10 per cent. However, a full 34 per cent are still undecided on the amount. The figures also vary considerably by continent. In Europe, no respondents have taken or plan to take a pay cut and in Asia just 15 per cent have, while in Australasia 71 per cent have, and in North America 52 per cent have.

Several leaders make the point that the actual impact on institutional finances of a leader’s pay cut is fairly minimal. However, one UK vice-chancellor notes that the 20 per cent cut they took in 2018 “helps fund six graduate teaching assistant posts”.

Irma Becerra, president of Marymount University, Virginia, initially took a pay cut, “but the board disagreed with pay cuts so we stopped it after three months”.

For Pamela Gillies, vice-chancellor of Glasgow Caledonian University, “short-term pay cuts were gestures that lost significant credibility when senior pay rose again shortly afterwards – in some high-profile cases to significantly more than the previous level of pay.” Hence, Glasgow Caledonian’s executive team “gifted a significant portion of our salaries to the Common Good Fund of the university”, which supports students in need. “This higher level of gifting will continue beyond the pandemic.”

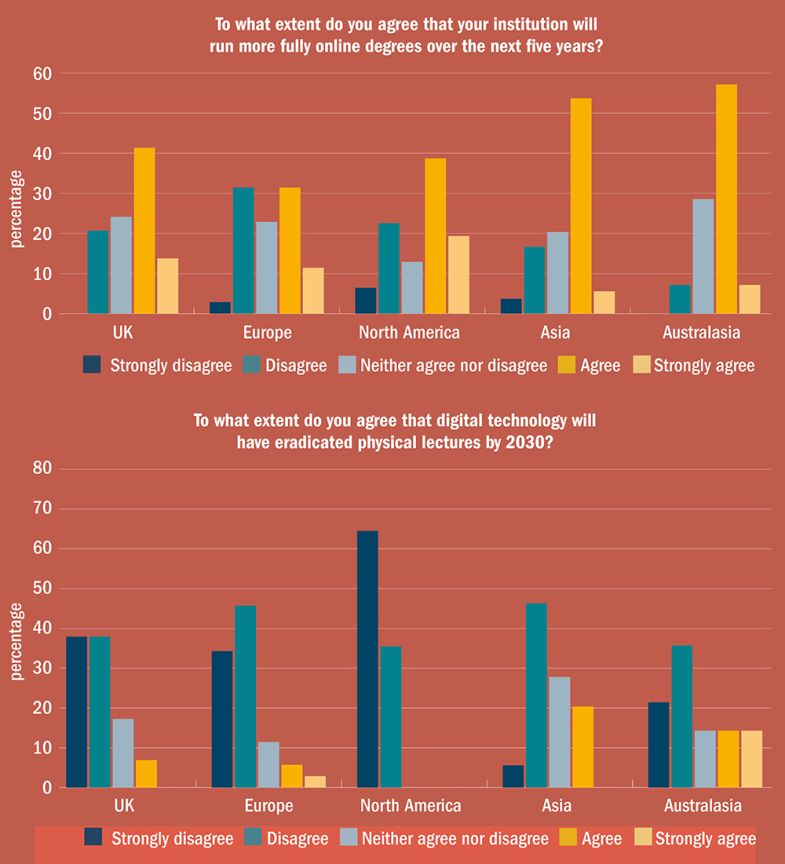

Looking to the future, one obvious question is whether the pandemic has changed pedagogy forever. There have been no end of affirmations in these pages and elsewhere that the best features of online education should be retained for the long term. Yet students themselves have appeared distinctly lukewarm to the charms of the digital experience, amid plummeting student satisfaction and demands in some quarters for refunds. And, for all the relative success of the overnight move online, it seems the leaders are wary of holding on to too much digital provision, too.

Asked to what extent they agree that their institution will run more fully online degrees over the next five years, 53 per cent of respondents agree. Yet that figure is actually a slight decline on the early days of the pandemic, when 55 per cent of respondents agreed with the same proposition. The number disagreeing has also grown slightly, from 23 to 24 per cent, although the proportion of those strongly disagreeing is lower.

Enthusiasm for online degrees is highest in Australasia, but even there it has declined considerably, with the proportion of respondents expecting more fully online degrees falling from 89 to to 64 per cent. By contrast, expectations have held steady in continental Europe, but remain lower (43 per cent) than on any other analysed continent.

Many leaders note that the removal of the imperative to come to campus for lectures would have a detrimental impact on the wider campus life that students consistently say that they value very highly. Indeed, just 13 per cent of respondents agree that digital technology will have eradicated physical lectures by 2030. This compares with 19 per cent of respondents to THE’s first leaders survey, carried out in 2018 – long before the pandemic. In other words, the Covid experience has made leaders more rather than less convinced that physical lectures have a long-term future. Enthusiasm for them is particularly strong in North America, where no one expects their extinction. It is weakest in Asia, but even there, just 20 per cent of respondents think that physical lectures will have disappeared by 2030, compared with 52 per cent who don’t.

“Digital technology will be a part of the lectures, but not eradicate physical lectures,” says the International Christian University’s Iwakiri.

Some respondents, particularly in Asia and Africa, point out that permission for online provision must be given by their governments. Others note that while school-leavers may not be interested in fully online provision, older learners might be. “Undergraduate students clearly see campus as the centre of action; they want the full ‘university experience’,” says Erik Renström, vice-chancellor of Lund University in Sweden. “For international students and, in particular, lifelong learning, online learning will become increasingly important.”

One Asian vice-chancellor notes that online education could be a particular blessing for students from rural communities, but its potential is marred by issues around digital access.

Enthusiasm for blended learning is markedly higher than for fully online degrees, with 86 per cent of all respondents agreeing that their institution will increase its provision of blended degrees over the next five years, compared with 84 per cent in the 2020 survey. Enthusiasm is particularly high in Australasia and the UK.

Sarah Springman, rector of ETH Zurich, cautions that “blended learning is actually quite expensive in terms of time and resources. I can see it could be very much more beneficial in the future, but there will be lots of different methods of doing it.”

She notes that 22 per cent of the 42 per cent of ETH students who answered a recent institutional survey said that they want to be on campus every day – perhaps because they couldn’t work at home or they wanted to see their friends. “Most of the others said they would like two days working from home so they don’t have to travel as much. But almost nobody said they want to study for five days at home. People recognise that labs, projects and other value-added things are what a university is really about.”

Perhaps that recognition partly explains why, despite everything, 86 per cent of respondents feel positive about their student recruitment over the next five years. Even in Australasia, 78 per cent feel positive, although a much lower proportion feel strongly positive than elsewhere.

One Australian vice-chancellor says it is hard to know what the medium-term impact of Australia’s border policy on international students will be. However, “domestic student recruitment is likely to be stable or growing”. And Auckland’s Freshwater detects a common sense that “we know we are going to be able to recruit students, but the mix and size and shape of cohorts may be different. Some of them may be offshore online; everybody is planning for that.”

Student recruitment will no doubt be boosted by a strong understanding of what students want. Regarding their perceptions of would-be students' priorities, the factor most commonly cited by leaders (33 per cent) is teaching quality, followed by graduate employment prospects (21 per cent) and cost of tuition and position in league tables (both 12 per cent). However, the list varies considerably by region. Australasian vice-chancellors overwhelmingly deem a university’s position in league tables to be students’ overriding concern, while UK vice-chancellors plump for graduate employability.

But how accurate are these perceptions? Times Higher Education’s Student Pulse Survey suggests that they are broadly right – as least as regards the concerns of the international students who make up the bulk of the survey sample. The latest iteration of the survey, carried out between 28 June and 12 July, with a sample size of 367, reveals that leaders are right to deem quality of teaching students’ primary concern. However, cost of tuition is their next highest concern, coming above even graduate employability – perhaps reflecting the higher costs that international students typically face. University leaders ranked those factors the other way around.

Students also rate quality of research slightly higher than a university’s position in league tables, while leaders assume that rankings are considerably more important: “In our discussions, league tables loom quite large, particularly for international students,” confides Queen’s University’s Deane.

One striking aspect of the Student Pulse Survey results is that, despite students’ professed concern about the environment, leaders are apparently right to assume that a university’s commitment to sustainability is relatively low on would-be students' priority list. Nevertheless, 80 per cent of leaders profess that pursuit of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) informs how their institution operates, with only 3 per cent disagreeing. Sentiment is particularly strong in the UK (89 per cent) and Australasia (92 per cent) – notwithstanding one Australian leader’s remark that “in this part of the world, the SDGs carry little importance”.

According to Gillies, the SDGs are “at the heart” of Glasgow Caledonian’s latest strategy. “Our impact on them will drive our work in education, research, knowledge transfer with industry, and community development and civic engagement. Our performance as an institution will be measured by our success in impacting each of the 17 goals,” she says.

Meanwhile, all of Makerere’s activities “must align with [Uganda’s] National Development Plan, which is aligned to the SDGs”, notes Nawangwe.

Those activities include research, of course. And 79 per cent of leaders say the SDGs will influence their institutional research priorities over the next five years – although that figure drops to 73 per cent in North America and 70 per cent in Asia, and rises to 93 per cent in Australasia.

Unsurprisingly, SDG 4 – quality of education – is deemed the most important SDG by respondents, followed by SDG 3 (good health and well-being) and SDG 13 (climate action). However, the UK and Europe both deem the last of those the most important.

“They are all important. But without an adequate response to the climate emergency, many of the goals will be unattainable,” says Gillies.

Asked what the most important institutional measures are to address the climate crisis, leaders opt for energy-efficient buildings, followed by a zero-carbon commitment and a plastic-free campus.

The assumption that quality of teaching is students’ primary concern is reflected in leaders’ professed top priorities in their jobs, cited by 56 per cent of respondents (up to three answers was permissible). However, quality of research comes a close second (51 per cent), with balancing the budget (27 per cent) and student satisfaction (22 per cent) a distant third and fourth.

However, the regional differences are again considerable, with quality of teaching being topped by quality of research in Europe, by balancing the budget in Australasia and by attracting funding/philanthropy in North America. Asia is the only region to place internationalisation in the top three (although behind quality of both teaching and research).

According to Boston University’s Brown, the North American finding is a result of the preponderance of private institutions in the US: “‘Balancing the budget’ implies that [governments] give you the money and that is all the money you have to spend. In the US, we go out and get funding from private sources.”

According to Michael Spence, vice-chancellor of UCL, the other regional differences are also intuitive: “UK universities are anxious around their social licence to operate, and that is essentially around the fact that [students] don’t think they are getting value for money. European universities are keen to lift their [research] game. Asian universities are on a rise and thinking about teaching and research but also reaching out more generally. Australasian universities are responding to government agendas around employability.”

But he adds that pursuit of a certain priority is not necessarily an affirmation that that factor is the most important aspect of what a university does. “No UK v-c would say quality of research wasn’t important or balancing the budget wasn’t something that kept them up at night,” he says.

Gillies’ immediate priority in the post-Covid period is “promoting the mental health and well-being of the whole university community…since it is an essential driver of the university’s performance in all of the other domains”. And she is not alone in seeing mental health as a major challenge.

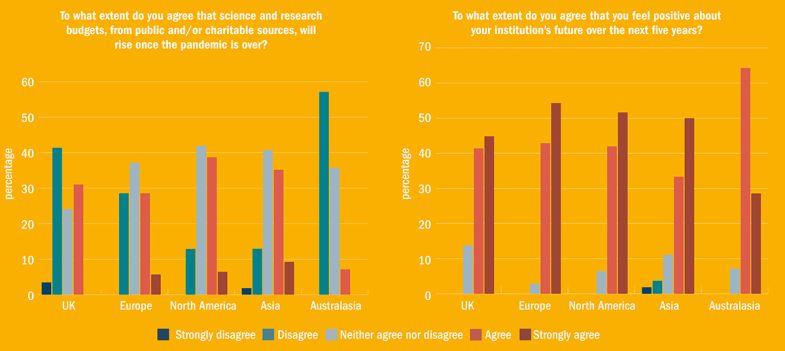

Another factor that will influence other performance domains is the pandemic’s effect on individuals’ and nations’ economic health. Asked to what extent they agree that the coronavirus will reduce their government’s willingness to invest in higher education over the next five years, leaders’ opinion is evenly split, with 37 per cent agreeing and 38 per cent disagreeing. Pessimism is strongest in Australasia and the UK, while optimism is strongest by some distance in North America, where just 16 per cent expect a funding decline.

This is a marked change from last year, when pessimism was strongest in North America. Europe and North America are also the only regions in which optimism about university funding has grown over the course of the pandemic. The darkening of mood is particularly marked in Asia.

The change of mood in North America may be a result of the inauguration of Joe Biden as US president, whose first few months in office were marked by large spending pledges on higher education and research. But even in North America, optimism about research funding has declined since last year – though not as much as elsewhere. This has allowed North America to overtake the UK as the most optimistic region about research funding, amid doubt that the UK’s research spending pledges would be confirmed in this week's spending review. In North America, 45 per cent of respondents expect research funding to rise over the next five years, against 13 per cent who do not.

Optimism about research funding has declined particularly precipitously in Australasia, making it by far the least optimistic region regarding research funding: just 7 per cent expect a rise, against 57 per cent who do not. The UK is the only other region where pessimists outnumber optimists, but there is a high degree of uncertainty all round, with 38 per cent overall unsure.

According to one university leader, “governments may be willing to increase investment in R&D but the public finance situation has deteriorated sharply in most countries, so there is a huge dilemma there. Countries know that unless they invest more in R&D they will never catch up.”

According to Erlangen-Nuremberg’s Hornegger, “in times of crisis, politics should invest in research and innovation, and in Germany they actually do.” But Queen’s University’s Deane voices a common view that, when it comes to research funding, different disciplines are likely to have diverging fortunes.

“While the Canadian government has been taking on huge debts to manage the social impact of the pandemic, it has nevertheless also made special investments in biomedical research and has promised to continue to do that. If, like me, you work on literature, I would imagine the prospects are pretty bleak for increases in research funding in the immediate future,” he says.

Leaders’ confidence in their ability to navigate such uncertainties is linked to their sense of autonomy. Asked to what extent they agree they have the freedom to take the decisions they feel are necessary to secure a bright future for their institution, 74 per cent of respondents agree, about a third of those strongly. The greatest preponderance of agreement is in the UK, North America and, perhaps surprisingly, Asia. By some distance, it is lowest in Europe, where rectors are typically elected or appointed by governments. Even there, however, 63 per cent agree they have the autonomy they need, against only 11 per cent who disagree.

One impediment to autonomy is government bureaucracy. For instance, Marcia Abrahão Moura, rector of the Universidade de Brasilia, notes that “Brazilian laws do not allow the public universities to take their own decisions”, while Hornegger is most concerned by “over-regulation of private institutions by the government”.

But politics appears to be the biggest constraint. That concern is reflected in respondents’ answers to the question: “What do you see as the single greatest threat to your university over the next 10 years?” More than 40 per cent of respondents mention noises off, chiefly from politicians and wider culture. For instance, Wim Wiewel, president of Lewis & Clark College in Oregon, is most concerned about the “ambient societal environment opposing free expression and [promoting] suspicion of science”. A UK vice-chancellor adds: “If the state is constructive rather than destructive, we can prosper. If it is malevolent, by accident or design, I’d be less sanguine.”

Of course, socio-political headwinds have financial implications. An Israeli leader explicitly links the two; their biggest concern is “decreasing public funding and an anti-intellectual culture developing in the nation”.

Financial worries are explicitly cited as a major institutional threat by 46 per cent of respondents. In addition, 23 per cent mention student demand or student quality, which also has financial implications for institutions.

Reflecting the relative scepticism about the demand for fully digital education, just 2 per cent of respondents see a threat in digitalisation – or “disruption in education that will make physical education redundant”, as a rector in Spain puts it. An Australian vice-chancellor perceives a threat from “new models of credentialling from big corporations”, presumably thinking of the online offerings being developed by the likes of Google; Georgia Nugent, president of Illinois Wesleyan University, also worries about “new entrants into the industry”.

Meanwhile, when asked what are the most important things for their institution to achieve in the next 10 years, digitalisation is mentioned by just 3 per cent of respondents.

The most common theme of responses to that question is improving the quality or teaching or research, mentioned by 23 per cent of respondents. Financial factors are cited by 20 per cent, and the same proportion mention achieving external impact.

The next most popular themes relate to improvements in rankings or reputation (10 per cent), environmental sustainability (9 per cent) and graduate quality and employability (9 per cent).

For all the challenges that the future evidently holds, respondents are overwhelmingly confident that their particular institution will fare well. A full 91 per cent agree that they feel positive about their institution’s future over the next five years, against just 2 per cent who do not – all of them in Asia. Europe records the greatest optimism, with 97 per cent agreeing that they feel positive and no one disagreeing.

The least positive group of respondents are those whose institutions saw the biggest pandemic-related financial hits in income associated with domestic students. This group are markedly more pessimistic than those suffering most from declines in international student revenue, suggesting that the latter group sees the Covid-driven downturn as a temporary blip.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, positivity correlates closely with the degree to which respondents feel they have the freedom to take necessary decisions, with 33 per cent of those who strongly disagree that they have the necessary freedom feeling negative about their institution’s futures: by far the highest proportion.

Again, new leaders are the most positive about the future, with all of those who have been in their current positions for a year or less feeling positive, the vast majority strongly so; those in position for more than 10 years are most likely to disagree, but even among this group, 86 per cent feel positive, with only 6 per cent disagreeing.

“‘We are the future’: that is our motto,” says Saima Hamid, vice-chancellor of Fatima Jinnah Saima Hamid Women University in Pakistan, who has been in her current job since 2019.

Whether such optimism is justified, of course, is something that only the future can disclose.

POSTSCRIPT:

Data analysis was carried out with the assistance of Binta Hussaini, a data scientist in THE’s data team.

Print headline: Running a university during a pandemic

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login