As an international student from Pakistan, the first time I heard the term “academic integrity” was in a first-year orientation session at a small liberal arts college in the US.

To officially join this community, I had to sign its honour code, which obliged me to “honor myself, my fellow students, and the college by acting responsibly, honestly, and respectfully in both my words and deeds.” I signed – but I was surprised by just how seriously my pledge was taken. In particular, I was shocked that I was now permitted to pick up an exam paper from the campus centre and work on it whenever and wherever I wanted, with the entire institution trusting that I would not consult any additional resources in the process.

With millions of students in Covid-enforced online classes now taking exams under a similar system of trust, no doubt many more students are experiencing that shock. Yet mine was particularly intense because I had grown up in a society where cheating on tests was celebrated.

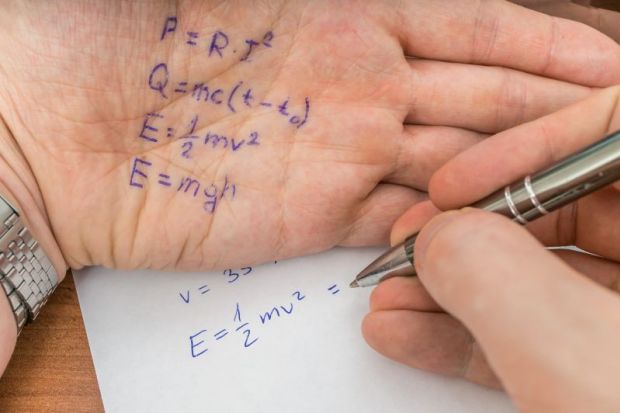

At my high-income private school in Lahore, cheating was regarded as a duty to friends and even a badge of honour, signifying your ability to outsmart authority figures. Hiding paper chits in socks, swapping answer sheets and touching parts of your face to indicate the right multiple-choice answer to friends were all acts of kindness. I remember when our teacher left class during a sixth grade history test and someone flung a textbook from one end of the classroom to another as everyone cheered. Copying homework was not even considering cheating, and swapping notes with friends was deemed peer-to-peer support. Any “teacher’s pet” who did not take part was labelled selfish and unethical.

Meanwhile, any school official who reported cheating risked facing violence, while examiners themselves were often complicit. In 2017, Karachi’s education board revealed that 11 examination centres overseeing government schools were involved in leaking examination papers, and raids took place in Karachi and Hyderabad following identification of cheating through WhatsApp groups.

Nor was university entry exempt from corrupt practices. It was not considered wrong for someone to offer to take the SAT for you (with a fake ID) for 50,000 rupees (£227). One of my friends, an international student struggling financially in the UK, did not hesitate before accepting payment to write someone else’s master’s dissertation for them. I also remember another friend being contacted by a tuition centre, working with formalised cheating groups, about buying the question paper for our upcoming A-level chemistry exam.

Even parents – who, after all, grew up with the same socialisation – see good grades merely as a stepping stone to social mobility, and valuable in that sense regardless of how they are achieved. Knowledge gained in school is regarded as something merely to be regurgitated with no expectation that it should have real-world applicability. This, in turn, ensures that the next generation continues to prioritise individual over collective success and has no interest in tackling corruption in deliberately weakened institutions.

The Hindi word jugaad – recently defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as “a flexible approach to problem-solving that uses limited resources in an innovative way” – is often used to celebrate such well-executed individual and collective acts of cheating. Shortcutting one’s way to the top, rather than studying hard, is regarded as the real mark of intelligence where I grew up.

But if parents and examiners are too set in these destructive ways to change, perhaps there is hope yet for the students. The honour code I encountered in the US made clear that it was preparing me for a whole lifetime, during which it was incumbent on me to uphold my honour, especially when no one was looking. It reframed academic integrity as a matter of being honest with myself and the community of learners to which I belonged. And, despite my background, it made a big impression on me. If Pakistani schools and universities were to adopt honour codes of their own, shifting responsibility for preventing cheating from ineffective and undermotivated authority figures to the students themselves, I am sure it would make a similar impression on many other students.

However, it is important also to say that this cultural shift was not easy for me to make, and it was only gradually that I began to feel like an active member of this new community, with all the personal responsibilities that this implied. This is why, as institutions in the US welcome an increasing number of international students, they must take care to acknowledge and respond to their different cultural conditioning around integrity.

First-year orientation programmes must focus on how individuals from different parts of the world can come together to co-create a shared community based on a new set of common values and behaviours. Such programmes must also include spaces for open and non-judgmental conversations about cheating.

Most important, they should stress that integrity is a matter of honouring your relationship with yourself and your community, rather than simply avoiding the consequences of violating university policy. After all, those for whom cheating has been normalised as a necessity in life do not expect to face consequences.

Sara Pervaiz Amjad is a graduate student at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login