“I was very blunt with Dominic Cummings,” says Mariana Mazzucato of a meeting in Number 10 Downing Street with the man who was then the prime minister’s most senior adviser. “I think you’re part of the problem,” the UCL economist recalls telling him in 2019.

Cummings – a volatile personality who once had a colleague ejected from Downing Street by an armed police officer, before his own abrupt ejection last year – had invited her into Number 10 to talk about his second biggest priority, after Brexit. This was setting up a UK equivalent of the US Defense Advanced Projects Research Agency (Darpa) with the aim of sparking a science and innovation boom that would lead on to his utopian/dystopian vision (delete as you see fit) of the UK as the Silicon Valley of Europe.

Mazzucato told Cummings that his Darpa idea was “looking at one-tenth of the puzzle”.

Before taking a step like that, she sees a need to “step back further” and ask a fundamental question: “What is the role of government?”

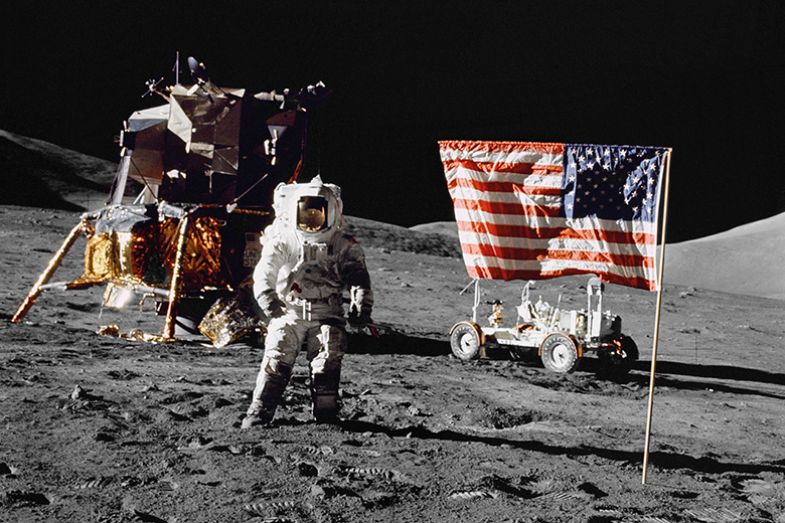

That’s where Mazzucato’s new book, Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism, comes in. It criticises a “flawed ideology about the role of government” that has gripped many Western nations since the Reagan-Thatcher era, according to which wealth creation is solely the concern of business and government’s role should be minimal or non-existent. In a contrasting vision of what government can do, the book looks at the Apollo programme to land astronauts on the moon. Begun by the US federal government under President Kennedy in 1961, the programme “took up 4 per cent of the US budget and involved over 400,000 workers in the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (Nasa), universities and contractors”. Apollo created a huge array of “spillover” technological innovation, such as in computing (you need a powerful, small computer to steer a lunar module), which led on to “what we today call software”, Mazzucato writes.

The Apollo programme, she argues, came through the sort of “mission-oriented” approach she advocates – partnerships between the public and private sectors aimed at solving key societal problems. The book “encourages us to apply the same level of boldness and experimentation to the biggest problems of our time”, such as pandemics and climate change.

Mazzucato, professor of the economics of innovation and public value at UCL, has made rocket-propelled progress across the policy universe thanks to the success of her breakthrough book, The Entrepreneurial State: Debunking Public vs Private Sector Myths (2013). As well as being instrumental in the UK government’s adoption of a mission-oriented industrial strategy, she has been consulted by Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (pictured below) on plans the high-profile left-wing Democrat was developing for a Green New Deal (billed by the congresswoman as the “moonshot of our generation”). As special adviser to former research and innovation commissioner Carlos Moedas, she has also been a key force in shifting the European Union’s Horizon Europe research programme to a mission structure. And, as a public figure, she has been profiled in The New York Times and Wired, and can be regularly found explaining to TV news presenters why they are wrong about economics.

But how does an academic get to the point where she is invited into Downing Street to be (constructively) blunt with the prime minister’s feared adviser?

“Before I wrote The Entrepreneurial State, I was just a normal academic; I would write stuff and say: ‘Here’s the policy implications’ and then leave it there,” explains Mazzucato, whose family moved from Italy to the US when she was five after her nuclear physicist father, Ernesto, took a position at Princeton University.

That book developed out of a pamphlet published in 2011, when Mazzucato was about to become RM Phillips chair in the economics of innovation at the University of Sussex (she studied economics at the New School for Social Research in New York, which aims to “generate progressive scholarship in the social sciences and philosophy”). It was Mazzucato’s attempt to argue against the austerity taking hold across the West as the dominant policy response to the financial crisis, stressing that governments and civil servants should desist from taking the tyres off their own wheels by cutting the state and public spending and instead understand that “wealth is created collectively from public, private [and] third sector institutions”, she says.

The Entrepreneurial State looked at Darpa as an example of the US government’s proactive role in the creation and commercialisation of new technology (forerunners to the internet and the Global Positioning System (GPS) emerged from the agency) and argued that pretty much every element of the iPhone originated in federally funded research. This view of governments as “wealth creators” was a challenge to the sort of thinking typified by then UK prime minister David Cameron, who in 2011 described civil servants as “enemies of enterprise”.

After writing the pamphlet with what she humorously describes as “a bit of zeal”, she gave numerous presentations on it, which eventually led to her being invited to speak at the European Commission just as the book came out in 2013. Delivering a message seen by some working in government as “uplifting” (against a grim background of austerity) is what, she thinks, “started to get me…invited to speak to high-level departments”, so that “very quickly...I was being invited to give keynotes across the world, at that kind of presidential/prime ministerial level”.

But you can have enough of that kind of thing, it seems, and in 2017 she moved to UCL to establish the UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose.

“The reason I then set up the institute at UCL was I was sick of me just going in [to speak to politicians and civil servants], almost as a TED talker, being clapped and [hearing people say], ‘Oh wow, you make me happy,’” recalls Mazzucato. “I was like: ‘Yeah, whatever. I’ve got to go back [home] and I’ve got four kids to feed and papers to write and grants to get.’ That wasn’t the life I wanted to lead: just to be a single person going in and inspiring the masses. That makes no sense.”

The institute was her attempt to “systematise this new way of thinking” and develop a “world-class, cutting-edge master’s in public administration that tries to rewrite the curriculum for the Civil Service” on the back of The Entrepreneurial State’s message, says Mazzucato. Teaching is rooted in the vision that “in order to have dynamic public-private partnerships, you need an equal amount of ambition within the public sector,” she adds.

The institute’s other work includes a report for the Scottish government on the creation of a Scottish National Investment Bank, aimed at guiding it towards a mission-oriented approach to tackling societal challenges, and a project with the Basque cooperative Mondragon (which includes a university) to develop a cooperative vision for the green transition.

Mazzucato also “worked very closely” with Greg Clark, former secretary of state in the UK Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), to press the argument that the nation’s industrial strategy should “go away from” older ideas of “just being a list of sectors to fund” and orient itself around missions or grand challenges. Mazzucato later co-chaired a UCL commission to advise the government on that, alongside former universities minister Lord Willetts.

Indeed, the industrial strategy did set out four grand challenges when published by Theresa May’s government: to “put the UK at the forefront of the AI and data revolution”; to “harness the power of innovation to meet the needs of an ageing society”; to “maximise the advantages for UK industry from the global shift to clean growth”; and to “become a world leader in shaping the future of mobility”, including automated vehicles.

But since then, the industrial strategy seems to have been forgotten by Boris Johnson’s government.

“The blueprint is there…but the energy got derailed,” says Mazzucato. “A lot of extremely smart people I was working with in BEIS…ended up getting pulled away” to work on Brexit, she adds. Another confounding factor, she continues, was “random thoughts that people like Dominic Cummings had about ‘the Civil Service sucks: let’s bring in geeks’. Really? If you don’t even think of the Civil Service as being wealth-creating, then forget it: why do you need a Darpa?”

You get the sense that Mission Economy stems partly from Mazzucato’s frustrating encounters with some in the UK government – who, as she sees it, either lack ambition or refuse outright to rethink an outmoded attitude to government’s role in the economy that dates back to Margaret Thatcher.

The book’s big argument, says Mazzucato, is about the need to “get rid of the old narrative” that government is “simply about fixing market failures”. And about the need to look at “the real question: how can [government] be an active co-creator and co-shaper of markets alongside the private sector?” That is crucial, she writes, at a time when capitalism is “stuck” – with no answers to the environmental or pandemic crises.

As for universities’ role, she thinks “the foundation of the US model” as a hugely successful innovation state lies partly in the “interface between universities and big public problems” in public labs such as Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, run by the California Institute of Technology. “I feel that bit is just completely missing in the UK innovation system,” Mazzucato says.

One huge policy challenge is to translate innovation into “good jobs” for a broad spectrum of society – not just those with degrees from the most prestigious universities or based in already affluent places. But Mission Economy is focused on changing perceptions about the role of government, without offering too much on how to spread the benefits of innovation equitably across different kinds of people and places. It’s a crucial question with no easy answers, Mazzucato observes. But, broadly, she thinks one key step would be to “create less of a division between the welfare state and the innovation state”.

“If you look at the northern regions” in England, she continues, “they have lots of public services and public service workers” and could be “hotbeds” for unifying the welfare and innovation states. She has a “dream” to work with the Manchester United footballer and food poverty campaigner Marcus Rashford on school meals that are sustainable in their production and distribution. That sort of approach could be replicated “with all public services: public transport, public education, public health”, she thinks.

Until then, there’s a battle to be won in terms of changing minds about the role of government. Yet perhaps there’s fruitful ground even in the UK. The pandemic has seen new ideas about becoming “self-sufficient” in innovation (partly driven by fears about reliance on equipment made by China’s Huawei for building the 5G network) in the ascendant within the Conservative Party, and a “particular emphasis...on industrial strategy and innovation”, according to one recent account in The Times. Maybe that means dusting off the neglected industrial strategy from 2017.

Mazzucato finds it “amazing…how the ideology is so strong in many people’s heads that as soon as you talk about reviving and rethinking the state it’s: ‘Oh, she’s talking about the 1970s.’” Such critics should “drop their ideology” and “listen to what I’m saying. It’s not about random projects and putting all your money in one thing. It’s actually about having a portfolio approach.”

Many have tried to turn the page on the Reagan-Thatcher era of government. But coming during the pandemic, at a time when voters see a much greater role for governments in protecting them and helping them live better lives, Mazzucato’s book might be better timed for the political mood than most.

Mariana Mazzucato’s Mission Economy: A Moonshot Guide to Changing Capitalism was recently published by Allen Lane.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login