When Christopher Hill left the UK in 2008 to take up a role as director of the graduate school at the University of Nottingham Malaysia Campus, the eight-year-old institution that he encountered was “a completely different place” compared with the one he left seven years later.

In its early years, the UK’s first purpose-built overseas branch campus was heavily focused on teaching, he says. But, by 2015, research activities had picked up and Hill – who was, by now, director of research training and academic development – had started to note the emergence of “student clubs, workshops and public talks – the lifeblood of what a university is”.

This gradual emergence of a campus culture, he believes, is typical of the development of branch campuses.

“In the early days…there’s still a sense of lack of identity. You’ve got a lot of people attending a university without any real experience of the place where the [mother] university comes from. And you have a lot of people teaching in that university possibly without any real experience of the place in which [courses are] now being taught,” explains Hill, an expert on transnational education (TNE) who is currently associate professor in the Faculty of Education at the British University in Dubai. “You’ve got this disconnect between international staff, local administrative staff and students. But, over time, [the branch campus’] identity evolves.”

The University of Nottingham Malaysia was not quite the first branch campus in Malaysia – that accolade goes to Monash University Malaysia, established two years earlier. But it is among the pioneering models for international branch campuses (IBCs), duplicated, modified and reimagined numerous times since the turn of the millennium – not least by Nottingham itself, which established its parallel China campus in 2004.

For their host countries, the establishment of branch campuses by universities typically from more developed higher education systems is seen as a way to drive up the quality of local offerings through the example they set and the competition they offer. And the mother universities appreciate the opportunity to create regional research bases, increase their access to international students, boost their global reputations and perhaps even make some money along the way.

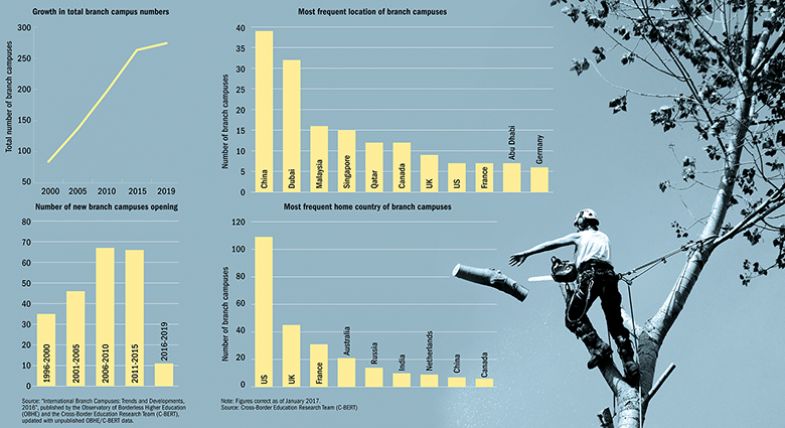

According to data from the Observatory of Borderless Higher Education (OBHE) and the Cross-Border Education Research Team (C-BERT), hosted at Pennsylvania State University and the State University of New York at Albany, the number of international branch campuses (IBCs) across the world grew from 84 in 2000 to 263 by 2015, located in 76 countries and catering to an estimated 180,000 students.

The Middle East and East Asia have been among the most popular destinations for such campuses. According to C-BERT’s website, China has been the most popular location for branch campuses, with 39 as of January 2017 (with another five in Hong Kong), followed by Dubai with 32 (and another seven in fellow emirate Abu Dhabi), Malaysia with 16 and Singapore with 15.

However, the appetite for this flavour of internationalisation is clearly cooling. Since 2016, just 11 IBCs have opened, according to the data, while several other campuses in the works have failed to materialise.

The US and the UK are by far the most common sources of branch campuses, with 109 being affiliated to US universities and 45 to UK institutions (France was third, with 31, while Australia had 21). But both countries have seen recent cases of universities pulling out of branch campuses or closing them.

The University of Warwick, for instance, backed out of plans to open a campus in California in 2017, citing concerns about regulatory constraints in the golden state and “global political challenges”. The University of Aberdeen, meanwhile, confirmed earlier this year that it was abandoning its plan to establish a site in South Korea, as the downturn in the oil and gas industry had led to “reduced demand for the types of degrees in offshore engineering originally envisaged” for the campus.

Meanwhile, Texas A&M University scrapped plans for an Israeli campus in 2015, instead launching a marine research centre in collaboration with the University of Haifa.

A 2015 survey of internationalisation staff by the European Association for International Education found that opening branch campuses had become their lowest priority. The focus had shifted to strategic partnerships and student mobility. For instance, that same year, UCL confirmed that it was moving away from a model of branch campuses and towards a network of institutional and academic partnerships with universities around the world. Its Adelaide campus closed in 2017, replaced by a partnership with the University of South Australia, while its Qatar campus is set to shut in 2020.

The slowdown in growth is not necessarily a surprise given the financial and reputational risks associated with launching such sites and the serious issues that have plagued some branch campuses. The University of Central Lancashire, for instance, was rebuked by the then UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, in 2013 after it established an “unauthorised” branch campus in the buffer zone between Greek and Turkish Cyprus. It was also criticised by Amnesty International for plans to expand into Sri Lanka amid allegations that the country’s government committed war crimes during the brutal conclusion of its war against the Tamil Tigers in 2009 (Uclan eventually partnered with a local institution to deliver two courses from 2017). It also emerged in 2013 that the institution would lose up to £3.2 million in the collapse of its planned Thailand campus, a joint venture with a local businessman.

A series of interviews with leaders of UK branch campuses in 2015 found that they often had little managerial experience and rarely received enough support from their home institutions. Serving deans and pro vice-chancellors regarded such international roles as “career suicide”, according to the paper, “The challenges of leading an international branch campus: the ‘lived experience’ of in-country senior managers”, by Nigel Healey, a TNE expert who is now vice-chancellor of Fiji National University.

Several institutions have also overestimated their ability to attract students and underestimated the difficulty in navigating the local environment and monitoring standards. The University of Reading’s Malaysia campus, which opened in 2016, made a £27 million loss last year, for instance. An internal document seen by Times Higher Education notes that the outpost “opened later, and cost more than planned”, while recruitment is hampered by its location “in an area that doesn’t have the best reputation in Malaysia”.

Meanwhile, Aberystwyth University said in 2017 that it was planning to close its Mauritius campus just two years after it opened. The campus was built to accommodate 2,000 students, but just 106 enrolled in its second year.

“The 2000s were a bit of a gold rush era for branch campuses,” says Jason Lane, interim dean of the School of Education at the State University of New York at Albany and co-director of C-BERT. “A lot of [institutions] rushed in with a lack of understanding of what it really takes to operate a multinational organisation or to deal with a local education system, or even to set up a new university – because most of our universities have been around for decades if not centuries. So I think there was a lot of jumping first and then eye-opening later.” Now, he adds, while universities still “see the benefits” of establishing a branch campus, they are also more clear-sighted about “the drawbacks and the risk” – which is only heightened by the increasingly unstable geopolitical environment.

Location and numbers of branch campuses

OBHE director Richard Garrett agrees that the increasingly nationalist outlook in many parts of the world will ultimately be a “net negative” for the launch of new branch campuses.

“The most determined [and] strategic institutions will keep doing it because it’s core business for them...But for those that are a little more hesitant and less experienced, it’s definitely a reason to wait, or not to do it,” he says.

The slowing growth is a “healthy” development that might result in “better thought out, better funded” campuses, he believes. But he also suggests that the failed outposts command too much attention, and people tend to “not notice the more ordinary successes”, even though there are many more of them.

“We certainly roll our eyes when we see headlines that call out one particular failure or change of direction and imply that that means that the entire IBC enterprise is somehow implicated or imperilled. I just don’t see the evidence for that,” he says. “The idea that IBCs would somehow quickly become either dramatically successful in terms of surplus financially or would have some kind of amazing pay-off for the institution in terms of mobility or brand was always going to be unrealistic.”

At the same time “it can be quite hard to say the model is successful in a simple sense when there’s so much variation” between the different campuses, he concedes.

Richard A. Williams is principal and vice-chancellor of Heriot-Watt University, which has campuses in Scotland, Dubai and Malaysia. He agrees that this paucity of understanding regarding the breadth of branch campus types can lead to misconceptions about their purpose and outcomes.

“Branch campuses are often talked about in a slightly condescending tone. ‘Oh the university [sees] this as some sort of cash cow.’ That is absolutely not our strategy,” he says. Heriot-Watt’s campuses are “distinguished by the fact that students on most of our programmes have mobility to move between locations because we’re operating the same curriculum, the same standards, the same exam paper [across all of them]”.

None of Heriot-Watt’s branch campuses have been set up as “a far-away campus to get on with its own strategy. Ours are set up as an integral part of our core strategy,” Williams adds. Like several other early adopters, including Nottingham and Monash, Heriot-Watt has created fully fledged campuses, which have developed to offer degree programmes across the sciences, social sciences and humanities.

Another model is to build diversity via partnerships with a range of different universities on the same site. The exemplar of this approach is Education City in Qatar, which was established by the Qatar Foundation for Education, Science and Community Development in 1997. As well as UCL's Qatar campus, this hosts six US branch campuses and one from the UK and one from France, each focusing on a different discipline. The site is also home to one domestic institution, Hamad Bin Khalifa University.

Meanwhile, some branch campuses more closely resemble offices, offering just one or two specialist programmes, either as a strategic decision to fill a gap in the local market – perhaps alongside a local partner – or because they have not yet grown into larger campuses.

Dubai’s Hill predicts that the future will see more of these partnership and boutique approaches to branch campuses, as opposed to large single-university campuses, because “the level of risk is lower”. Moreover, as educational standards improve in many of the traditional host countries for branch campuses, “they’re no longer as dependent on the foreign provider. They don’t have to say: ‘We’ll take whatever you want.’”

He adds that the increasing number of universities interested in branch campuses means that, for host countries, “it’s not necessary that one university runs 27 programmes. What’s necessary is that a university leverages its expertise to run programmes that are relevant in context.”

He cites the example of University of South Wales in Dubai, which was established last September in partnership with the local aviation authority and offers courses related to aeronautics. “I don’t think we’ve come to the death of branch campuses: I just think we’re evolving to the next stage,” he says. “The first stage was about access: host countries need access to international degrees. Then it was about capacity building. And the next stage has got to be about impact and the relevance of TNE” in terms of offering courses that local students and employers value, he says.

But the OBHE’s Garrett takes a different view. He believes that branch campuses will look “more and more like the parent institution, at least in terms of breadth. It’s naive to imagine that the university that in its home country took 50 or 100 years to really achieve its current breadth and depth is going to magically appear out of nowhere in five years in another country given all the unknowns...But, no question, the most developed and ambitious ones are very much adding disciplines, adding research capacity, finding their niche, and that’s all key to their long-term success,” he says.

C-BERT’s Lane adds that branches will become “more integrated into the organisational structure” of the parent institution, rather than being something of an appendage.

Margaret Gardner, vice-chancellor of Monash University, says that the success of her institution’s Malaysia campus is “in large part” down to its “strong alignment to the broader goals of the university”, via factors such as student mobility, research activities and funding opportunities.

Garrett highlights RMIT University as an example of an institution that is now focusing on integrating its collection of sites around the world into a network: it has three campuses and two sites in Australia, two campuses in Vietnam and a centre in Spain. Such initiatives are still rare, but are beginning to occur among institutions with more mature branch campuses, Garrett says.

One example of an institution that took such an integrated approach from the offset is New York University, which established a campus in Abu Dhabi in 2010 and one in Shanghai in 2012. It also has 12 offices across the world.

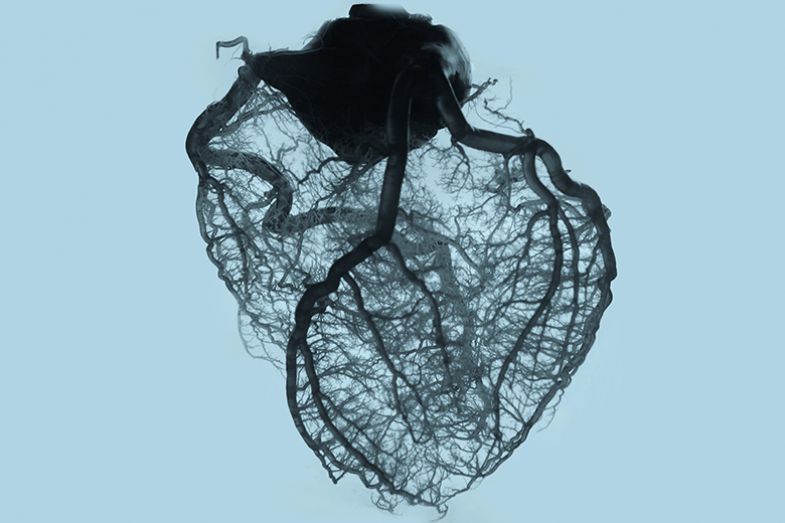

John Sexton, the institution’s president between 2002 and 2015, says that what the institution has is not a branch campus system at all but, rather, a “global network”. This is “a metaphor for an interconnected and circulatory world” – although Sexton’s example of what he means is decidedly local: “the neighbourhoods of New York City interconnect and are circulatory, but everybody is New York”.

This, he says, helps to assure high standards on every campus: “Our analogy would be that much as the quality of blood that circulates in an organism affects the entire organism, what this [approach to branch campuses] does is to create an interest everywhere in maintaining the health and quality of everything in the system.”

Unlike most branch campuses, the international sites are “not designed for the local population...they’re for the global population”, according to Sexton, who is currently Benjamin F. Butler professor of law at New York. They are full research universities, with very exacting entry standards.

One of the problems with the “hub and spoke approach”, such as Qatar’s Education City, is that the branches’ lack of integration with the home campus means that it can be hard to persuade quality academics to work there. New York undergraduates choose to study primarily at one of the three main “portal campuses” but take three of their eight semesters at one or more of the other sites.

Sexton says that the network model has led to a “huge upsurge in both the quality and the attractiveness of an NYU education”, with the annual number of student applications growing from 34,000 to 84,000 over the past 15 years. He predicts that by 2050 there will be around a dozen universities with global networks inspired by NYU’s model.

“As a general strategic move, the embrace of the fact that the world is a globalised community is so self-evident that notwithstanding that there have been failures, universities are going to have to adapt to this,” he says.

Just as the branch campus model itself has evolved over the years, the host and home countries involved in these outposts are also changing: in some cases, in direct response to shifting political winds.

Many UK universities have strengthened ties with European partners in the wake of the Brexit vote, for instance, with some planning new branch campuses on the continent – partly in an effort to ensure that they remain eligible for European research funding.

King’s College London and Germany’s TU Dresden announced in 2017 that they were collaborating on creating the UK university's first European branch campus, in Dresden. Lancaster University's own German outpost, in Leipzig, is due to open in September, as does Coventry University's campus in Wrocław, Poland.

But it is not all one-way traffic. The Technical University of Munich told THE in May that it was planning to open a campus in London, possibly as a joint venture with Imperial College London, “to send a signal against this crazy Brexit”.

Meanwhile, there are signs that US universities are becoming more interested in opening sites in Latin America: a region that historically has had very little branch campus activity, despite its rapidly growing population and its proximity to the US. Texas Tech University and Arkansas State University have launched sites in Costa Rica and Mexico respectively, while New Mexico State University is set to open an outpost in Mexico in 2021. Lane says that the state of New Mexico had to pass a resolution to approve the last, “which is interesting given all the rhetoric around the issues to the south of the US. If these [campuses] are successful...we’ll see more US institutions looking to move into Latin America,” he predicts.

Lane adds that despite the slowdown in new openings, student enrolment across international branch campuses continues to increase, which may in part reflect “geopolitical instability” and tightened immigration controls in branches’ home countries. They are becoming “new gateways into an American education or a British education”, he says.

Elsewhere, China has been a popular site for other countries’ overseas outposts, but may soon start exporting branch campuses across southern Asia and Africa – the region covered by its gargantuan Belt and Road project – in an effort to increase its soft power, Lane hypothesises. Xiamen University, for instance, established a Malaysia campus in 2015, which already has more than 4,500 students.

And while Malaysia issued a moratorium on new university campuses in 2017, it has also been actively seeking expressions of interest from institutions in Japan, which has become more interested in exporting branches. Currently, three Japanese universities are looking into opening a campus in the country.

Malaysia sees the geopolitical benefit of a growing relationship, while Japan has a rapidly ageing population and is interested in using branch campuses to help compensate for that by attracting more immigrants to the country, Lane says.

In the Middle East, meanwhile, Egypt has a goal of opening eight “international universities” next year in its nascent, unnamed new capital city 30 miles from Cairo. However, scholars have warned that such a move would pose a significant reputational risk to the institutions involved, given the country’s authoritarian regime and concerns over academic freedom. Last year, the University of Liverpool scrapped plans to open an Egypt campus after opposition from academics and students.

Garrett predicts that Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam all have potential to become future branch campus hubs as they are “very large, very fast growing, recognise the value of higher education for their own development and recognise that they need...some role for TNE to really make everything work. I think you need that combination and there aren’t too many countries in the world that fit all of those criteria.” However, whether they take off as hubs will ultimately “depend on politics and early success or failures”.

For Australian universities, the neighbouring giant of Indonesia is an obvious place to establish a branch campus. None have yet done so, but Monash is actively considering it. The university is already home to the Australia-Indonesia Centre – which undertakes research focused on bilateral benefit in partnership with five other Australian institutions – and the Monash Indonesia Representative Office, which was established in 2016 to build on the university’s academic and alumni links in Indonesia.

However, some other countries that could potentially benefit from the branch campus model have rejected the idea. India is a prime example. In 2010, the government approved a bill that would have provided a legal framework for overseas universities to establish branch campuses there, in a bid to drive up the quality of local universities. However, the country has since shelved the idea, instead focusing on its plan to create domestic “institutes of eminence”.

Garrett says that the branch campus model has always been associated in India with “neo-colonialism, profiteering and elitism”, and discussions about it “tend to get very polarised very quickly…No one, whether it’s an institution, a politician or a regulator, has managed to carve out enough space in the media to portray IBCs as net positive rather than net negative,” he explains.

Meric Gertler, president of the University of Toronto, is also sceptical about branch campuses, although his concerns lie closer to home. One of the reasons that public confidence in higher education seems to be “under siege...might be the fact that growing numbers of universities have essentially weakened their ties to their local communities by investing in other communities elsewhere”, he says.

Gertler says that Toronto has been invited many times to open a branch campus abroad but has always declined “because we think we can have access to the benefits of internationalisation in other ways that don’t undermine our tie to our local community”.

These strategies include building research linkages and partnerships with leading universities and scholars around the world, including joint research centres overseas; promoting the mobility of students and academics; and leveraging alumni abroad to provide placements for students.

Universities should have an interest in focusing on their local communities, not least because the quality of life in their local area is a “really critical factor” in attracting and retaining top faculty and students, Gertler says. He cites MIT and Stanford as examples of institutions that have risen in profile and stature “because they’ve been recognised for their impact in driving the dynamism of their local economies. It’s the strong local roots that enable a university to excel globally.”

But Heriot-Watt’s Williams believes that it would be a missed opportunity for UK universities in particular not to continue to embrace branch campuses.

“In a post-Brexit world...there remains a very strong opportunity, given the excellence of British education and its position in the world, to form effective collaborations and partnerships of different sorts internationally,” he says. “I wouldn’t be advocating a dampening. I think it’s going to develop and strengthen in the future.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Is the branch campus dying off?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login