Over the past decade, transnational education (TNE) has become a cornerstone of UK universities’ international work. About three times as many students were registered on UK courses delivered overseas in 2016-17 as were registered a decade earlier, with the total approaching 300,000 (excluding distance learners and statistical outliers).

This growth has not come easily. TNE partnerships are time-consuming and expensive to set up and maintain, and cost recovery is often impeded by low tuition fees. Budgets shift back into the black when students move on to UK portions of the course, so as long as this “articulation”, as it is often known, keeps pace with growth in overseas enrolments, TNE should be sustainable. However, our analysis suggests that TNE mobility is falling, with articulations making up a much smaller portion of new enrolments than many in the sector believe. If this is true, it’s time for a rethink about how and why we invest in overseas delivery.

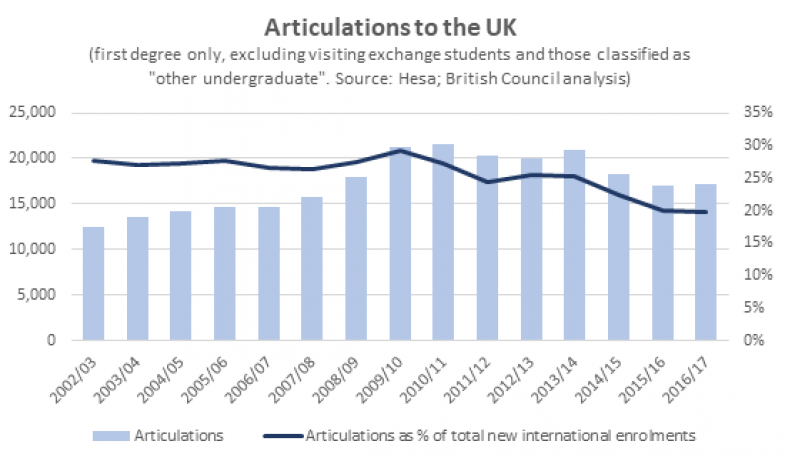

The Higher Education Statistics Agency does not supply data specifically on UK enrolments coming through TNE. However, we can estimate the number of students articulating by tracking the number of first-year undergraduates who are not in the first year of their programmes. This method also captures credit-recognition agreements, but it should approximate the overall trend – and the story it tells is not encouraging.

The number of international articulations to the UK appears to have dropped by a fifth since its peak in 2010-11. This group now makes up only about 20 per cent of new international enrolments, down from nearly 30 per cent six years earlier.

So why have articulations declined at a time when offshore undergraduate enrolments have grown? Three factors stand out: regulatory tightening, increased price sensitivity and the maturation of key markets.

Contrary to expectations, TNE regulations in key potential markets have not eased. In some cases, they have tightened considerably. In China, for instance, UK offshore enrolments have grown by two-thirds over the past five years, but the number of students transferring to the UK has risen by only a meagre 2.5 per cent over the same period. This is likely because of regulatory changes that have mandated a shift to delivering more course content in China. In addition, in other major potential TNE markets such as India, restrictions on programmes delivered by foreign entities have not been loosened.

While articulations to the UK held up through the global financial crisis, the subsequent crash in the price of commodities seems to have had an equal, if not more severe, impact. This can be seen in the fact that articulating students have been on a largely downward trend since 2009-10. It suggests that TNE has not functioned as an alternative pathway for mobility in distressed markets and may be more sensitive to economic conditions than full-degree overseas study.

Mobility through TNE has also been dented by the maturation of major markets such as Singapore and Hong Kong. The percentage of transfer/articulation students among all incoming first-degree students fell sharply from 2002 to 2008 and has not recovered since.

None of this means that TNE is a dead or dying activity. To the contrary, as economic and geopolitical power shifts eastward over the next decade, Western universities will be challenged to build their reputations and delivery based on a more globalised model. For many institutions, TNE will be the primary avenue to ensuring their continued relevance.

Yet the mobility patterns and financial realities of the next phase of TNE are likely to be starkly different from what the sector has experienced over the past 10 years. To succeed, universities will have to make more critical assessments of the benefits of potential partnerships, including more grounded expectations about mobility pay-offs.

Whereas TNE may once have served to broaden mobility pathways, in the future it will function best as a platform for UK universities to build deeper collaborations with overseas entities, featuring two-way mobility, research collaboration and engagement with industry. The next era of transnational education will require creative approaches to delivery, as well as a willingness to re-examine many of the business truths that the sector falsely believes to be self-evident.

Matt Durnin is global head of insights and consultancy at the British Council.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Changing transnational routes

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login