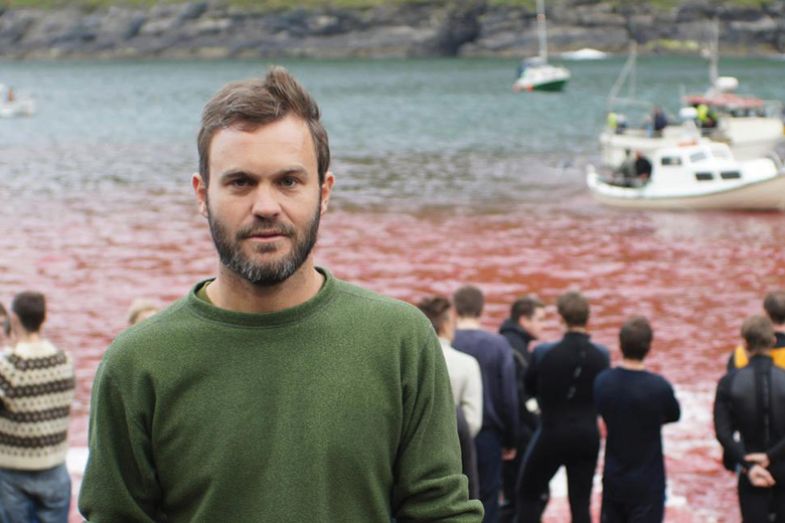

In the Faroe Islands, the notorious grindadráp – whale drive – takes place in full public view. The whales are corralled on to beaches and then slaughtered, turning the sea red with blood (pictured above). In the Caribbean island of St Vincent, on the other hand, whales are still hunted with harpoons, so the only way Russell Fielding could carry out some of the research that led to his new book, The Wake of the Whale: Hunter Societies in the Caribbean and North Atlantic, was to get his hands dirty and join a three-man whaling crew.

This proved a somewhat hair-raising experience. Fielding – assistant professor of environmental studies at the University of the South, in Sewanee, Tennessee – describes episodes when the motor cut out in mid-ocean, when the boat was almost overwhelmed by a rogue wave and when it was threatened by a sperm whale that “began swimming, menacingly fast, directly toward our bow”. He “heard the awful cries of dying dolphins in the hold” and was often tempted to “plunge the knife through the spinal cord, ending [their] drawn-out suffering”.

Yet the experience was also crucial to building trust. “I was down in St Vincent for three months,” Fielding recalls, “and had signed on as a crew member, but after several weeks I realised I was seeing the same thing every day and didn’t feel it was the best use of my time. So I spoke to the captain, Samuel, and said: ‘I’d really like to spend more days on shore, do more work in the archives, interview people, do other things beside whaling’, and he said something I’ll never forget: ‘You’ve signed on for three months. I expect you to be here every day, six days a week, for your job.’ I wasn’t being paid, but he was holding me to my commitment. At the time it was frustrating, but, in retrospect, it was really important because it confirmed my actual participation in the whaling event – I wasn’t viewed as just an observer who could come and go.”

Another way that Fielding (pictured below) established his credibility was by agreeing to eat the products of the whale hunt: something locals assumed that a dispassionate academic but not a closet anti-whaling activist might be willing to do. But this also proved something of a challenge.

“Imagine you put on a pair of knee-high rubber boots and stomp on a pile of fish that had been pulled from the sea and left in the sun for three days or so,” he writes. “To get an idea of what it’s like to eat blubber, both the flavor and the texture, after the fish have been thoroughly pulverized, stop stomping… and eat your boots.”

Over the course of more than a decade, Fielding has spent about nine months in St Vincent and nine more in the Faroe Islands (in one case, when research funding was running low, becoming probably the first and last person ever to offer a class in the Brazilian dance/martial art capoeira to the Faroese, in order to gain a bit of cash and extend his stay). Such deep immersion has enabled him to offer a vivid account of artisanal whaling: why it persists and even forms an important part of local identities. He also addresses the moral issues involved, but, to the disappointment of some, his perspective is not overtly critical. Although he is not “pro-whaling”, he does challenge some of the common critiques of the practice, which has led to a good deal of hostility.

“I am often assumed to be pursuing this project in order to cause whaling to come to an end,” Fielding explains. “That has never been my explicit goal…That lack of unambiguous opposition to whaling has cost me some credibility as an environmental scientist…I can recall one instance in graduate school when I was having a conversation with another student and she [burst] into tears and said something like: ‘You’re not even looking after those poor whales!’ On the professional side, I was a contender for a job at a different university and the person running the search told me that some of the opposition to letting me proceed was that I wasn’t sufficiently anti-whaling.”

A core issue, of course, is sustainability. In St Vincent, as Fielding’s book reveals, detailed records go back only to 2007 and he often had to rely on his captain’s “scrawled and bled-through notebook pages”. For the Faroe Islands, data for each grindadráp are available from 1709, something that probably “represents the single longest and most scientifically reliable quantitative record of human interaction with wildlife in existence” (and there may even be earlier material hidden away in the Vatican archives).

Both groups hunt pilot whales, which count as “small cetaceans” and so are not protected under the moratorium imposed by the International Whaling Commission. Careful analysis led Fielding to the conclusion that Faroese whaling is definitely sustainable and that Vincentian probably is too. Here, he enters highly disputed territory regarding what has been called the “ecologically noble savage”, whose “traditional societies” supposedly pursue “culturally embedded conservation strategies”.

In St Vincent, for instance, the whale hunt is restricted to the single village of Barrouallie, providing a part-time living to roughly 124 whalers and vendors. The grindadráp is confined to certain bays and beaches, involves amateur rather than professional whalers, and can only be triggered spontaneously, when a pod of whales is spotted by someone in the course of doing something else. Such formal and informal rules seem to have kept the whale catch to sustainable levels.

Fielding has reflected on and clearly likes the idea of “a wise ancestor who not only understood the principles of conservation but was also smart enough to know that the public would not understand them and so couched them within these cultural traditions”.

But he also admits that this is implausible. He suspects that we should instead think of a process akin to natural selection: “If there were methods of hunting that led to unsustainable practices, those practices would have died off simply for that reason.”

Industrial whaling has often exhausted stocks in particular areas, but the same can apply to more artisanal methods: “In the Shetland Islands – that’s the closest example to the Faroes – they overhunted all their whales, as did Newfoundland. You had very similar hunts taking place under very different cultural systems that did not serve to enforce sustainability and allowed overhunting to take place. We don’t see whaling in the Shetlands or Newfoundland any more.”

The Wake of the Whale would be fascinating just for its rich ethnographic account of the history and present state of whaling in St Vincent and the Faroe Islands. Yet, gradually, it also turns the mirror back on its readers, urging us to rethink our own attitudes to whaling.

There is a graphic account of a grindadráp that Fielding witnessed with his students. But although he certainly makes it sound like a horrifying experience, he also believes that it forces those of us who lead very different lives to confront certain realities that we otherwise shy away from: “Most of us meat-eaters do not see our meat at any point until it is prepared. If we think about it at all, we have a very superficial idea of what happens. We don’t think of the sounds or smells, the people standing with tools in their hands. Seeing that all happen in front of us was profound for my students and myself…Nobody lives off hunting in the developed world. In the Faroe Islands, they will have an average of six of these events each year. They also hunt wild birds and slaughter their sheep at home. Food production is much more central to daily life, and difficult to escape.”

Since the Faroe Islands are a self-governing dependency of Denmark in the North Atlantic, its inhabitants are white, European and affluent. Yet, for these few times a year, as Fielding puts it, “they do something which connects them with their subsistence past”. In explaining why, he cites Mike Day’s 2017 documentary The Islands and the Whales, in which a Faroese man goes hunting seabirds for the first time and is lowered on a rope down a cliff: “He’s talking about how he was so scared of falling but then remembered that the very same rope had held generations of bird hunters before him, and that gave him comfort to go ahead and do it.”

There is now increasing evidence that mercury contamination makes it dangerous to eat whale meat, and the Faroese health authorities have been issuing warnings to this effect. Yet Fielding suspects that islanders “would more much easily give up some imported food from the grocery store that was found to be dangerous, because they don’t have that kind of cultural capital tied up in it”.

Environmentalists, in Fielding’s view, can make matters worse. They often take the line that the Faroese don’t have to go on whaling because they are “developed and wealthy and have the same kind of material things that we have…What I find interesting is that among people aware of both societies, almost all are more approving of Vincentian whaling, because they see it as helping feed an impoverished group of people.” In reality, however, tropical and fertile St Vincent has many other food options, whereas many Faroese might fall back on imported and unhealthy fast food if they had to give up the free whale meat provided by the grindadráp.

Similarly, campaigners are happy to cite evidence of mercury contamination and berate the Faroese for failing to give up whaling, while hardly mentioning the industries (often based in their own countries) that have caused the far more damaging pollution problem in the first place.

Such double standards have led to an intransigent and troubling response that Fielding has observed during his many visits to the Faroe Islands since 2005. “When I first began my work in the Faroe Islands,” he explains, “there was really no anti-whaling activity happening at that time. There was a fairly robust argument within Faroese society about whaling: should we do this? There were multiple reasons given why the answer might be no. Pollution was one. Animal welfare and a move towards modernity were others. It was interesting to see this purely Faroese argument happening.”

But after the international maritime wildlife conservation organisation Sea Shepherd began campaigning against Faroese whaling in around 2010, “you saw that robust and diverse argument collapse into a solidarity movement asserting Faroese identity and sovereignty, where those people who were questioning the rightness of whaling had their voices silenced or chose to silence themselves”.

The result is that, in Fielding’s estimation, the anti-whaling movement has actually increased rather than reduced the number of whales being hunted and consumed.

“More people are [now] consuming whale meat as an assertion of who they are,” he says. “It would be amusingly ironic if it weren’t for the health issues.”

Russell Fielding’s The Wake of the Whale: Hunter Societies in the Caribbean and North Atlantic was recently published by Harvard University Press.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Pilot study

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login