International higher education has been a boom industry for Australia: just last week, researchers predicted that it was poised to overtake the UK as the world’s second most popular destination for mobile students.

Confidential data passed to Times Higher Education suggested that published figures routinely underestimated foreign enrolments in Australian universities, and also indicated that four institutions – the universities of Sydney, New South Wales and Melbourne, plus Monash University – now collectively host more international students than Scandinavia.

But boom is often followed by bust – and there are warning signs for the country’s third largest export industry, a critical revenue source for its universities.

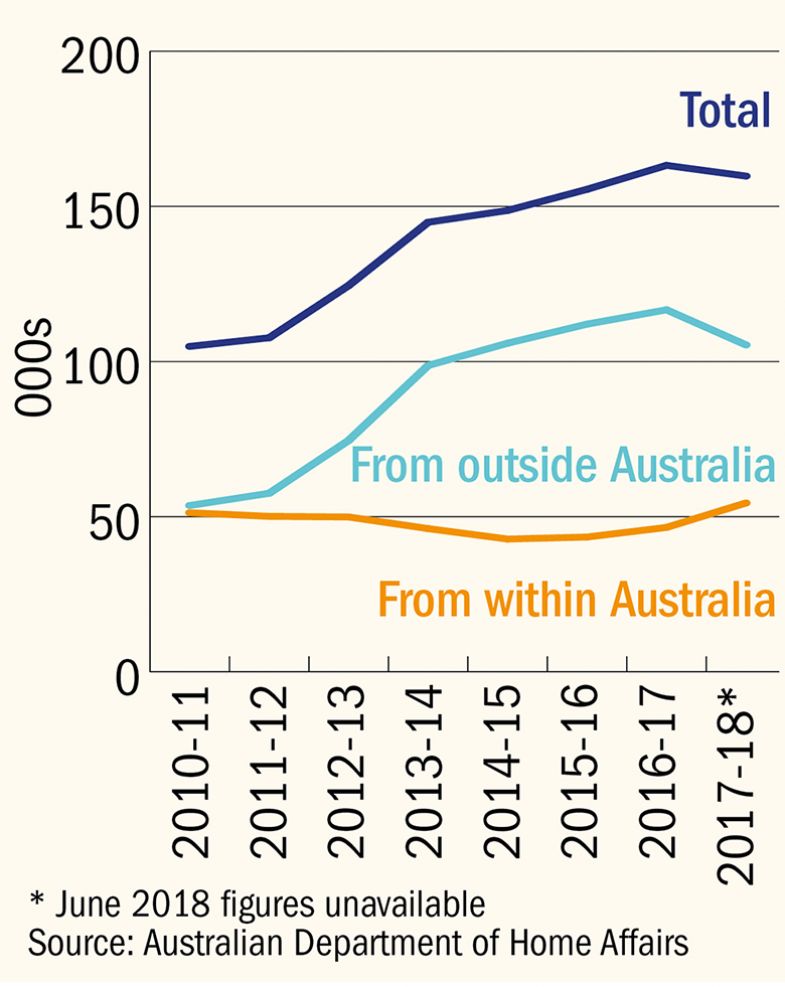

Department of Home Affairs statistics show that the number of would-be higher education students applying to come to Australia may be in retreat, with about 105,000 people seeking visas in the 11 months to May 2018 – down from 117,000 in the 12 months from July 2016 to June 2017.

A six-monthly report on the student visa programme, due in the next few weeks, may show that these “offshore” applications decreased in the last financial year. If so, it will be the first such decline since a “perfect storm” – a combination of a high Australian dollar, tighter migration rules, college bankruptcies and violence against Asian students – triggered a plunge in overseas enrolments between 2009 and 2012.

Since then, the sector has experienced explosive growth. The number of people applying for higher education visas from outside Australia shot up by 118 per cent between 2010-11 and 2016-17.

However, enrolment growth is now coming from “onshore” applicants – people who are already in Australia learning, working or holidaying who decide to stay on and study. By May, more than 54,000 people had lodged onshore visa applications – about 8,000 more than in the previous financial year, with June figures still to come.

Experts warn that this “churn” of potential students who are already in the country cannot continue indefinitely, with onshore applicants eventually graduating or returning home and leaving fewer fresh arrivals to replace them.

The International Education Association of Australia said that the industry could be destined for a “major downturn” when that happened. But chief executive Phil Honeywood said that this was about 18 months away, with many Chinese students already in Australia and planning to transition into higher education.

He said that they included school students who had long intended to enrol in Australian universities, and people undertaking pathway courses in English-language or vocational colleges.

Jodie Altan, director of global student recruitment at RMIT University, said that she expected enrolments to “taper off” over the next 12 to 24 months. “We’ve had a number of pretty solid years, but it is an unpredictable landscape,” she said. “If you think it’s going to keep going up and up, you haven’t been in this industry long enough.”

Ms Altan said that it was hard to say whether the downturn would be as severe as the last one, when overall international enrolments tumbled by 18 per cent. “Those factors were very difficult to predict,” she said.

“At the moment, it seems to be an issue of government relations. International higher education numbers are impacted by many factors that are well beyond our control. It’s very hard to say what will happen over the next 12 months.”

Foreign students applying for Australian higher education visas

Last time international enrolments declined, in 2009, the domestic higher education sector was in a phase of rapid growth. The federal government was on the verge of uncapping undergraduate places for local students, a move that flooded universities with new students and fresh money.

This time, however, the downturn in international tuition revenue is likely to coincide with declining public funding after the government capped university teaching grants last December.

This would leave Australia’s top universities without an obvious income growth stream to cross-subsidise their research and help them maintain their positions in global rankings – something that they have so far largely managed despite limited government money and stiff competition from intensively funded Chinese institutions.

Frank Larkins, a former deputy vice-chancellor of the University of Melbourne, said that this was a concern at a time of dwindling government research investment. “To maintain [their positions in] the rankings, universities have been looking outside government funding for growth. The logical way is through student fees, along with philanthropy,” he said.

For the past year, commentators have been warning that Australia’s international student revenue is insecure. One fear is that Australia’s difficult relationship with its biggest student source country, China, could undermine student flows, much like occurred recently in South Korea and Taiwan.

Potential flashpoint issues include Australia’s new foreign interference laws and possible Australian navy incursions in disputed areas of the South China Sea. Enrolments could also be destabilised by visa processing delays, safety worries, perceptions that Australia treats foreign students as “cash cows” or resentment over steep transport and health costs.

Other threats include overseas competition for international enrolments – particularly the UK’s recruitment of Chinese students – and signs that overseas degrees are losing some of their sheen in the Chinese labour market. Yet another danger lies in a rebounding Australian dollar, with indications that another mining boom – this time based on rare earth elements and metals rather than the traditional Australian staples of iron ore and coal – could push the currency back towards parity with the US greenback.

Professor Larkins said that the last international education downturn, when Indian higher education enrolments plummeted from 28,000 to 13,000, illustrated the vulnerability of Australian universities hosting some 135,000 Chinese students.

“If the Chinese government decided not to issue exit visas for students to come to Australia, or to go slow with processing them, that’s the risk. It has happened before. In the space of four years, the number of Indian enrolments more than halved. We’re not likely to have domestic students to take up the slack,” he said.

Flat offshore visa applications are not the only evidence of looming trouble for education exports. Enrolments at English colleges – often described as the “canary in the coal mine” for the broader industry, because students tend to polish their English skills before progressing to vocational or higher education – declined last year from some key source countries.

Department of Education figures show that enrolments in English colleges fell by 8 per cent from Taiwan, 9 per cent from South Korea, 10 per cent from India, 13 per cent from Thailand and 26 per cent from Vietnam. Mr Honeywood said that the decline had been masked by strong English enrolments from Brazil and Colombia.

“The challenge is how to persuade this cohort to convert into higher education,” he said, “given that most of these students can return home and get a free or very inexpensive undergraduate degree.”

john.ross@timeshighereducation.com

Rampant recruitment no threat to quality, universities claim

A rapid escalation in foreign student numbers has not compromised course quality or campus cohesion, some of Australia’s fastest growing universities have insisted.

The University of Melbourne, where overseas enrolments increased by 52 per cent between 2014 and 2017, said that it had “transformed student service provision” over that period and “continues to prioritise the student experience”.

The University of Sydney, where international enrolments rose by 99 per cent over the three years, said that foreign students provided “an enormous enrichment to the culture of our education”.

“Global connectedness is one of the pillars on which our undergraduate curriculum framework was built, and we have embedded the qualities of cultural competence in our degrees,” a spokeswoman said.

Confidential Department of Education statistics show that the two universities, along with cross-town rivals Monash University and the University of New South Wales, have absorbed a large share of the recent growth in international higher education. Sydney disputed its figures.

This could add to concerns about language problems hampering learning, or that multicultural engagement on campus has been undermined by skewed foreign enrolments – particularly at some Group of Eight universities, where up to 70 per cent or more of foreign students are Chinese.

The International Education Association of Australia said that half the net growth in international higher education enrolments between 2010 and 2016 had been concentrated in Sydney, New South Wales, Melbourne and Monash. “Four of the Go8 universities in particular are doing very well,” said chief executive Phil Honeywood. “We’re talking about a two-speed sector.”

But Mr Honeywood said that recent years had seen a “noticeable beefing-up of resources” for services focused on international students. These include mental health facilities, work-integrated learning – which gives students a taste of Australian life, as well as work experience – and accommodation on or near campus, often bankrolled by the four universities. “It means they’re close to campus and not having to worry about public transport issues,” he said.

Monash deputy vice-chancellor Sue Elliott said that her university was exploring new ways of helping Chinese students overcome unease about their English skills. “We’re working really hard on that, so that students aren’t taking two to three months [before] feeling confident in speaking out.”

The Australian National University, where international enrolments have risen by 61 per cent since 2014, said that student endorsement had remained high, with 83 per cent satisfied with the teaching quality. UNSW said that its approval rating in the International Student Barometer survey was more than 90 per cent.

“We are constantly seeking feedback from all students, including our international cohort, on ways we can further improve the overall university experience,” a spokeswoman said.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Is Australia’s foreign student wave receding?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login