An old joke in medicine is that there are only two treatments in neurology: you can either start, or stop, taking steroids. Of course, this is not wholly accurate, but it resonates because, despite all the advances of neuroscience, less progress has been made in the translation of knowledge from bench to bedside, and into new treatments for patients. Yet what is unarguable is the role that neuroscience has played in how we conceive of ourselves and others.

Matthew Wilson Smith’s The Nervous Stage explores this theme through a series of case studies of points of connection between drama and neuroscience, commencing in the 18th century and moving up into the 20th. While reading the book, I wondered whether I should consider it a work of cultural history: the author offers an overarching narrative and argument that runs through the monograph. This narrative offers a move from the interpretation of gesture in performance as a way of understanding the inner life of the character to a brute nervous sensationalism evoking mental states and emotions with immediacy in the audience, and then a return to interpretation through the influence of Sigmund Freud and August Strindberg.

In sketching this arc, Wilson Smith deftly describes many intellectual currents, some connections unknown to me and several memorable anecdotes. There is a great discussion, for example, of Dickens, Victorian melodrama and worries about the impact of the railways on the psyche and on health, including “railway spine”. However, there is some looseness as to the sorts of neuroscience drawn on as interlocutor to the theatrical practitioners – as when philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer’s reading of neuroscience is brought in relation to Richard Wagner – but in general the connections explored are illuminating and surprising.

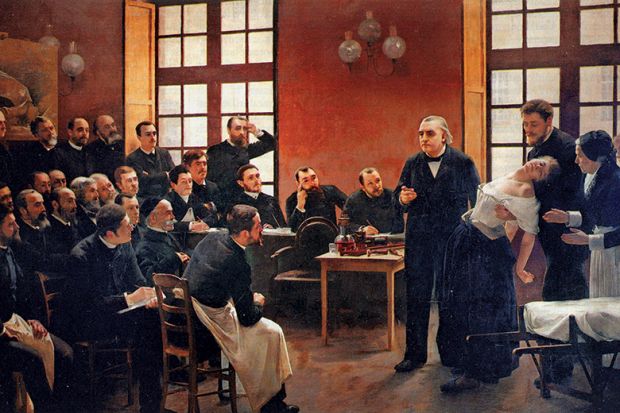

One of my favourite accounts of a deep intimacy between neurology and drama concerns Jean-Martin Charcot, whose methods of treating hysterical patients became a kind of theatrical performance, and Joseph Babinski. For all medical doctors, Babinski gave his name to the clinical sign (also known as the plantar reflex) whereby on stimulating the sole of the foot, the big toe points upwards – indication of central nervous system damage and perhaps a stroke. Here, however, we see another Babinski, a professor of neurology and despondent defender of Charcot’s theory of hysteria, who, on losing the intellectual argument, co-authors a play, The Deranged Women, under the pseudonym “Olaf”, for the Grand Guignol in Paris. Babinski went to see his own play, disguised with a false beard and using yet another identity – that of Alfred Binet, a fellow neurologist-playwright, and disciple of Charcot. Surrealism, as Wilson Smith notes, runs through both the play and the author’s viewing of it.

Despite the central narrative offered, I didn’t find an overview of the method by which the case studies had been selected. This led to a worry in the empiricist in me that the data – and hence the historical narrative – could have been otherwise. But given the prominence of the figures and theories discussed, Wilson Smith undeniably delivers what he sets out to do: a novel reading of theatre that stands in close relation to developments in the study of neuroscience. For me, he also offers a conception of neuroscience refreshed by its influence on us being not only via direct therapeutic innovations, but by complex, subtle and pervasive influences on our self-conception.

Matthew Broome is professor of psychiatry and youth mental health, and director of the Institute for Mental Health, at the University of Birmingham.

The Nervous Stage: Nineteenth-Century Neuroscience and the Birth of Modern Theater

By Matthew Wilson Smith

Oxford University Press, 240pp, £25.99

ISBN 9780190644086

Published 16 November 2017

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Exposed nerve endings

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login