Ever since John F. Kennedy set scientists the task of putting a man safely on the moon, the attractions of “grand challenges” – specific research goals designed to spur science in a particular area and achieve large-scale national or global ambitions – have been clear.

Now, such “moon shots” are increasingly being used by universities as a way of focusing and attracting support for their research endeavours. A recent report by the University of California, Los Angeles estimates that 20 major higher education institutions in the US and Canada are currently involved in or are actively leading grand challenge programmes in collaboration with charity donors, government or local industry, and says that the trend is growing worldwide.

Benefactors argue that such schemes are not only good for initiating a quick boost in scientific progress, but that they also have the power to capture the public’s imagination – therefore providing positive public relations and increasing popular support for investment in research.

But some academics feel uncomfortable with the amount of activity being centred on fashionable, big-banner goals such as curing cancer rather than on basic research that could have a wide range of potential applications.

Grand challenge programmes that are well structured and sufficiently resourced “can expand knowledge across science and technology frontiers, create a foundation for new industries and jobs, and catalyse breakthroughs in fields such as health, education and energy”, UCLA’s report into university-led initiatives states.

Research directors from the university – which is said to be the first in the world to implement such an approach at an institutional level – also report that “these moonshots can inspire youth – tomorrow’s change-makers, scientists, engineers, entrepreneurs, artists, and storytellers – and engage them in tackling tough problems”.

UCLA has two grand challenge programmes under way, supported by government grants as well as campus funds, industry sponsorships and philanthropic gifts. The first goal is to make Los Angeles County fully operational on renewable energy by 2050; the second is arguably less concrete: ending depression “as we know it” by the end of the century, the estimated cost of which is set at $525 million (£374 million) for the first 10 years alone.

Michelle Popowitz, assistant vice-chancellor for research and executive director of UCLA’s grand challenges office, said that, despite initial hesitations, the challenge of chasing a specific target struck a chord with the majority of academics.

“These are messy problems; they are not things that can be solved by one or two people,” she said of the challenges set. “What we try to do is bring people together from different disciplines to bring different perspectives that can open up a new approach…for many researchers, that’s why they went into academia in the first place.”

The motivations behind UCLA’s grand challenge initiatives include raising the university’s public profile as well as strengthening areas of expertise and fostering more collaboration between departments and, eventually, other campuses and research centres. “By planning to work together up front towards a common goal and framing research so that it fits together, we expect to have faster results,” Ms Popowitz added.

The UCLA report says that grand challenge goals should be “thoughtfully defined”, “not too broad” – allowing several possible paths towards the goal – and “not too specific”, permitting multiple disciplines to see the relevance of the goal to their work and interests. It adds that there must be a “compelling explanation of why the goal is now in reach”.

Some universities have held open competitions for seed funding among researchers to help identify grand challenges to pursue, while others have held town hall events on campus to ensure that the whole community has an input into the selection of projects.

The UCLA grand challenges report offers a number of recommendations for successful delivery, including ensuring that the commitment of the university leadership is clear for all to see, internally and externally.

Key strategies for success, it continues, include aligning fundraising programmes with the grand challenges to attract philanthropic support, and eliminating potential funding obstacles, such as restrictions on funding at disciplinary levels when a challenge requires cross-departmental effort.

The report advocates collaborating closely with industry, government and charity partners, establishing robust work plans for each goal, and including students in projects.

To ensure that momentum is not lost as work on the challenge stretches into years, the report underlines the importance of regular communications with staff and the wider community.

UCLA has since advised and worked with universities as widespread as Germany, Australia and the UK that are interested in pursuing their own grand challenge goals.

The rise in US interest in recent years can be attributed in part to a call to action by Barack Obama in 2013, when the then-president launched an initiative to expand scientific understanding of the human brain with the White House Office of Science and Technology. The UK government has also pushed university focus into similar initiatives, most noticeably with the creation of the £1.5 billion Global Challenges Research Fund (GCRF) in November 2015, aimed at driving UK science to compete with other world leaders in research addressing problems faced by developing countries.

A number of the UK’s biggest charities, including the Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research UK, have also sought to restructure their priorities in the past three years, placing emphasis on tackling bigger challenges over longer periods and moving away from the traditional model of handing out smaller grants for shorter time frames.

A strategy launched by CRUK in October 2015 unveiled seven grand challenges in cancer science, for which researchers were encouraged to bid for up to £20 million to fund projects of five years or more. Four successful teams were announced earlier last year, receiving the first round of funding valued at £71 million.

Looking to the longer-term future arguably gives researchers greater stability to achieve their targets over more realistic time frames, and some suggest that the scale of such projects reduces researchers’ pressure to publish frequently, ultimately leading to higher-quality research.

James Wilsdon, professor of research policy at the University of Sheffield, said that the move towards challenge-directed research was a “broadly positive and welcome trend” because it encouraged research that was more “user-driven” and ultimately more useful for social and economic needs. However, he advised, such a shift demands caution and “close monitoring”.

“Often the challenges themselves are framed pretty broadly,” he said. “This allows for a good degree of flexibility on the part of researchers in designing proposals and projects that fit within the broad challenge domain but still allows them to pursue agendas and questions that they would otherwise address through more responsive modes of funding.

“At the same time, clearly there is a need to monitor quite carefully the overall balance of funding within the system and the underlying health of disciplinary fields or questions that are less ‘fashionable’ in policy terms – especially when, as now in the UK, you’ve got a significant shift towards new challenge-directed funding programmes across the system as a whole.”

Pressure for academics to fit grant applications into a certain box – for instance, meeting the requirements set for GCRF cash – will also undoubtedly affect the future landscape of research.

“There’s a sensitive politics around which topics get identified, articulated or prioritised as a global challenge or grand challenge and which topics don’t make the cut,” Professor Wilsdon said. “The selection process here needs to be consultative, reflexive and very mindful of the tendencies towards sectoral bias,” he added.

rachael.pells@timeshighereducation.com

Grand challenge initiatives under way in the US

University of California, Los Angeles

UCLA’s “Sustainable LA Grand Challenge” aims to support Los Angeles County’s transition to 100 per cent renewable energy and to sourcing all its water locally by 2050, while also improving local ecosystems and human health, at an estimated cost of $150 million. The “Depression Grand Challenge” hopes to cut the burden of depression in the region by half by 2050, and to eliminate it by the end of the century, at an estimated cost of $525 million. The projects are being supported by campus funds, along with federal grants, industry sponsorships and philanthropy. Students are engaged in the projects through year-long research placements and, in the case of the depression challenge, training them to support classmates who might be at risk of suffering low-level depression or anxiety.

Georgia Institute of Technology

Styled as a “living learning community”, Georgia Tech’s programme involves 110 first-year students being admitted and placed in a single dormitory community. They are tasked with exploring solutions to social challenges guided by academics who identify broad focus areas such as energy, health or sanitation. Then, in small student-led teams, they look to implement their proposed solutions during the course of their undergraduate degrees, starting businesses and presenting their work at conferences. The scheme will double in size next year.

Indiana intends to invest up to $300 million over the next five to 10 years in three to five grand challenges. The first three are a “precision health initiative” that aims to transform healthcare in Indiana, and cancer treatment in particular, through broader application of precision medicine; a “prepared for environmental change programme” that aims to equip the state to cope with extreme weather patterns and the environmental changes that result; and the “responding to the addictions crisis initiative”, which seeks to build collaborations between the university’s seven campuses and industry, charity and government partners.

More than 800 UT Austin academics and students are engaged in the university’s Bridging Barriers programme, which draws on institutional budgets as well as support from donors and grant funders. The first theme to be selected is Planet Texas 2050, which aims to explore how the state will ensure the resilience of its built and natural environments in the face of increasingly extreme weather and rapid urbanisation.

Chris Havergal

POSTSCRIPT:

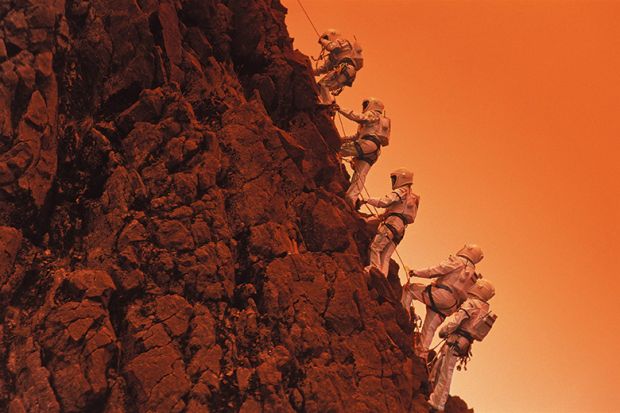

Print headline: Climb every mountain

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login