Students from the most advantaged areas are still at least twice as likely to enter most UK universities as their peers from disadvantaged neighbourhoods, according to new figures.

The latest equality data from admissions body Ucas show that, at 70 out of 132 institutions, the entry rate for 18-year-olds from areas with the lowest higher education participation was at least two times lower than the rate for students from districts with the highest participation. At 10 universities, this ratio was higher than 9:1.

However the data, analysed by Times Higher Education, also suggest that some of the country’s most prestigious institutions have made progress on narrowing this gap in recent years, despite still having some of the lowest proportions of disadvantaged students.

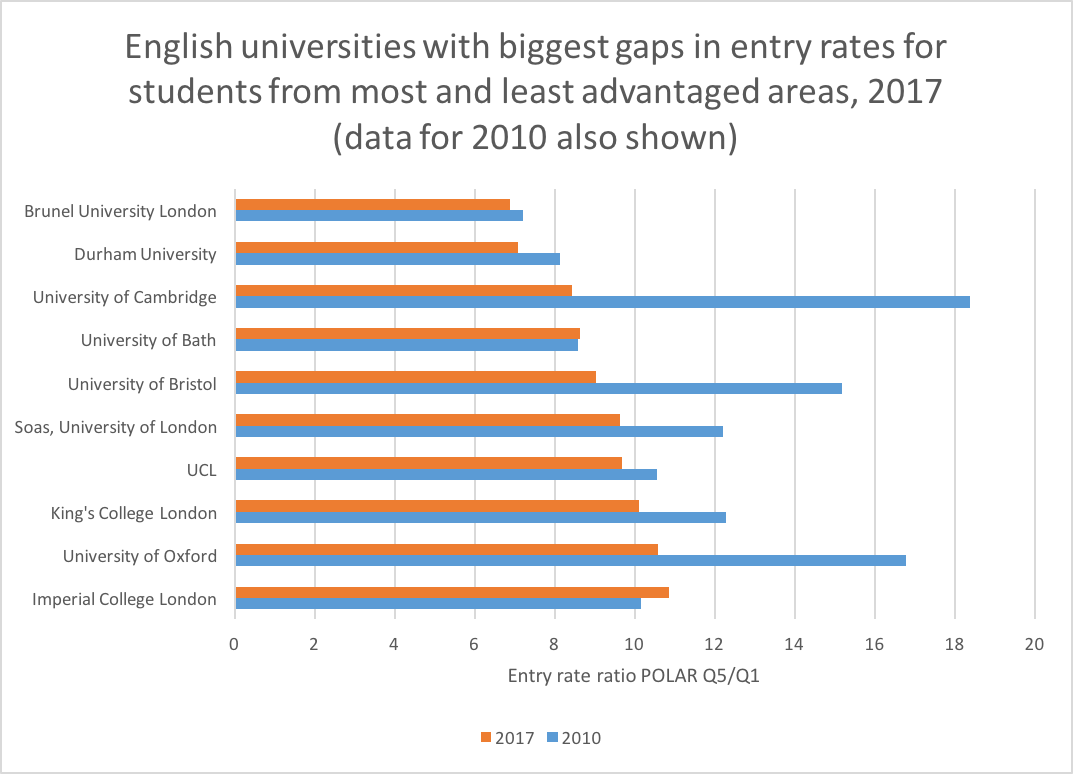

The figures, released on 25 January, show that for the first time since 2012 neither the universities of Oxford or Cambridge had the biggest gap for English institutions between the most and least advantaged student entrants.

Instead, Imperial College London, where the entry rate for those from the most advantaged areas was 11 times higher, was just ahead of Oxford, while Cambridge has fallen to eighth in the list of English universities with the biggest differences in entry rates.

Still, according to a separate analysis by THE's sister publication TES, just 5 per cent of 18-year-olds gaining a place at Cambridge last year were from the most disadvantaged “POLAR” areas, which are classified according to the number of young people who typically go on to higher education. This was slightly better than Oxford (4.1 per cent) and Imperial (3.8 per cent).

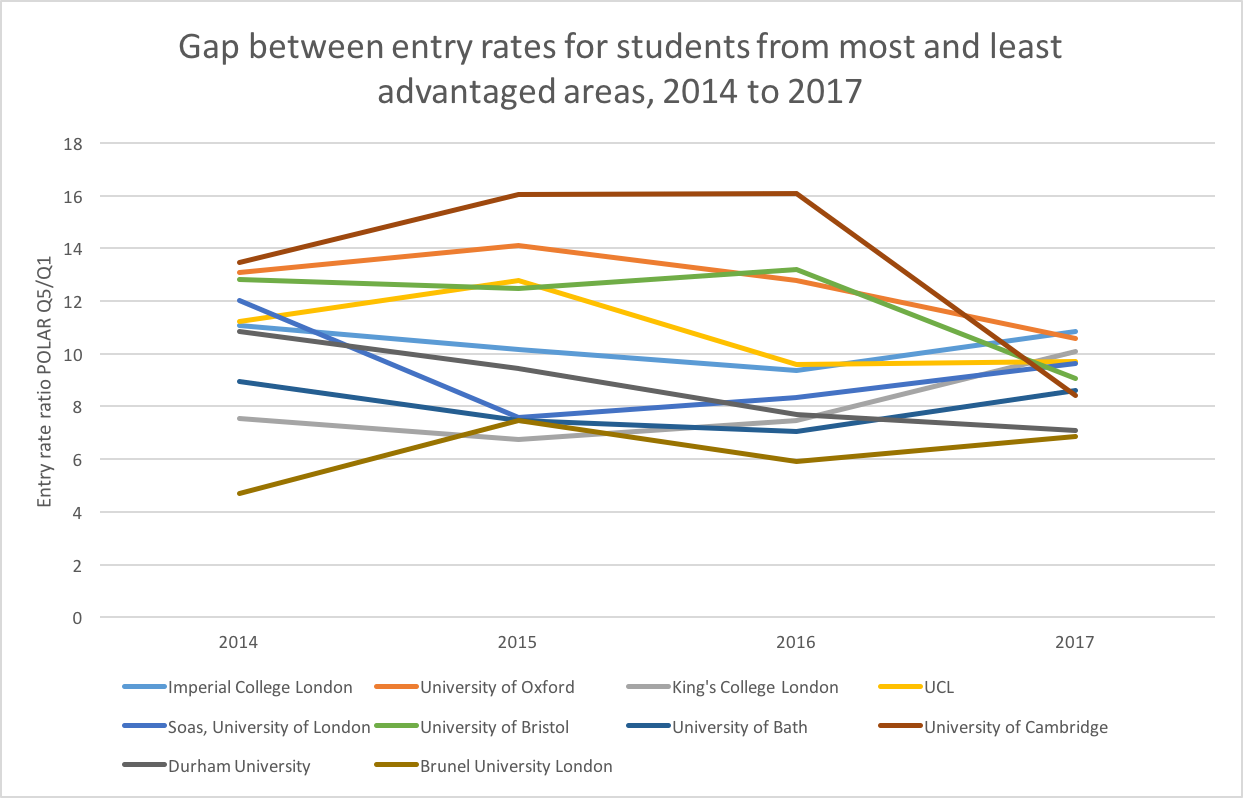

The data also show the universities where improvements in access have stalled in recent years. Ucas’ main end of cycle report for 2017 had already pinpointed that progress had slowed down since around 2014.

Some of the most selective institutions, including Oxford and Cambridge and the universities of Exeter and Bristol, have continued to see significant falls in the gap between entry rates for the most and least advantaged areas.

But others, most notably King’s College London, where just 3.5 per cent of placed students were from the most disadvantaged neighbourhoods, have seen the gap widen in the past couple of years.

Seth Fleet, lead data scientist for Ucas, said that it was important to view the POLAR statistics with some caution because they were heavily influenced by the area that a university typically recruits from.

For instance, London and Scotland tend to have very few people living in the most disadvantaged areas so institutions recruiting a lot of students from either place will tend to perform worse.

These data also do not account for the fact that students from advantaged areas are more likely to leave school with higher grades.

However, Mr Fleet said that the Ucas analysis did suggest that a number of institutions that were very unequal on POLAR entry rates in the past had made significant progress.

He also drew attention to the difference between entry rates and data on offer rates, which can be analysed by taking students’ grades into account. These contextualised data suggest that universities are, on the whole, not offering more places to students from advantaged areas.

Mr Fleet said, therefore, “if we want to get to a point where things are far more equitable in terms of participation in HE, the way to do it is to encourage more people to apply rather than changing offer-making practices”.

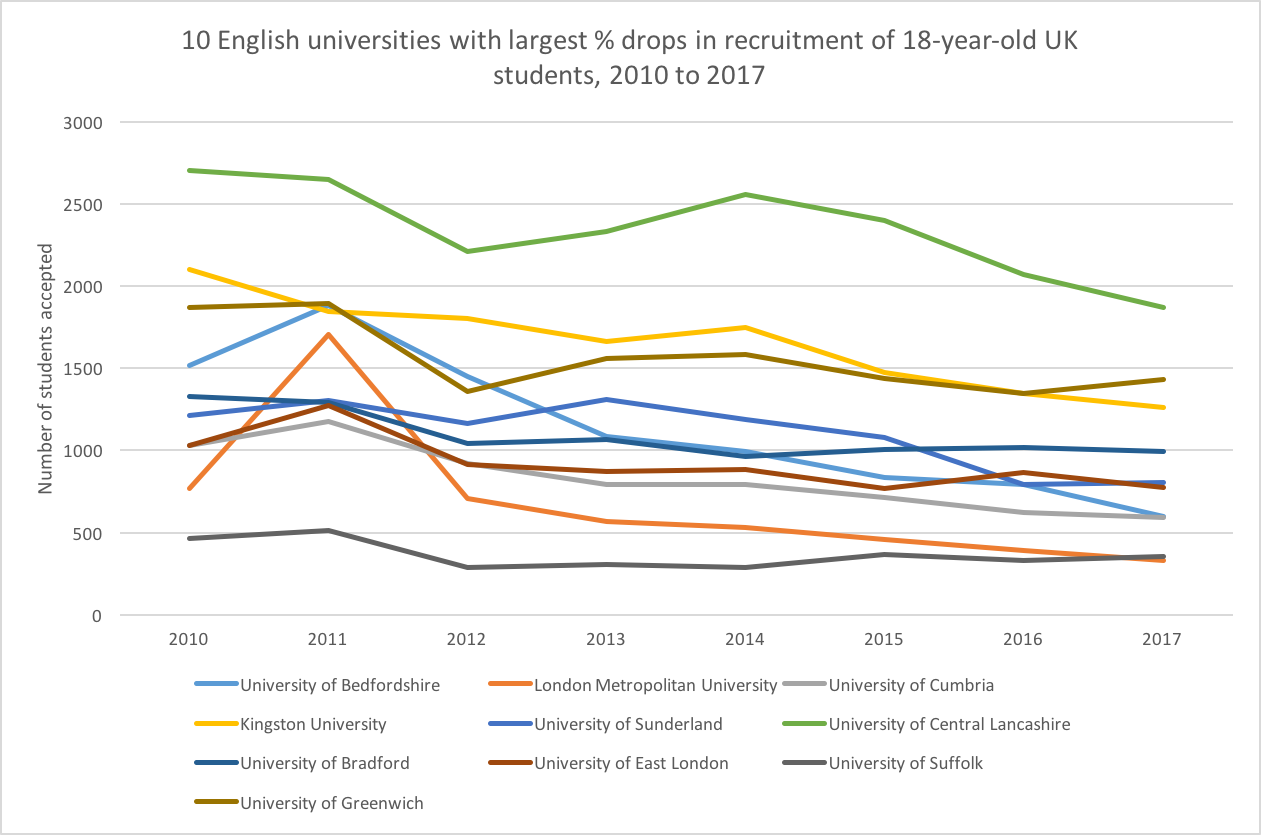

Meanwhile, the Ucas data release also contains the first figures on recruitment by provider for 2017, with a continuing trend for some large post-92 universities to admit much smaller cohorts of 18-year-old students.

For instance, among larger English universities, the University of Bedfordshire saw the biggest drop in recruitment from 2016 to 2017, with its intake of UK school-leavers falling by 25 per cent.

A number of institutions now recruit more than a third fewer 18-year-old students than they typically did in 2010, the last year before the sector began to feel the effect of higher tuition fees.

They include Bedfordshire, where the recruitment of UK school leavers in 2017 was 61 per cent below the level seen seven years before, and London Metropolitan University, which accepted 57 per cent fewer such students in 2017 compared with 2010.

Find out more about THE DataPoints

THE DataPoints is designed with the forward-looking and growth-minded institution in view

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login