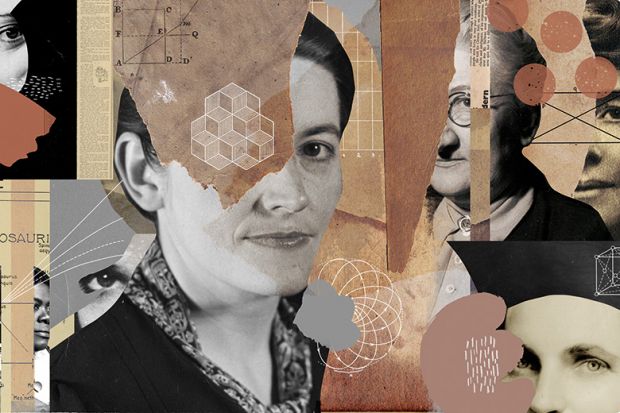

Next week will see the latest crop of Nobel prizes awarded – and unless this year is an extraordinary outlier, there will be few, if any, women among the recipients.

According to the Nobel prize website, 911 individuals have won a prize since 1901. Of those, 48 (5 per cent) have been women, yet most have won in the literature category – a traditional area of women’s strength – and a few in peace. Very few have won in physics, chemistry, physiology/medicine or economics.

Let’s call these fields PCPE. These are all disciplines in which women are severely underrepresented as scientists, much less as Nobel laureates. Nevertheless, the startling scarcity of female laureates is frequently remarked on, and it is significant that even PCPE laureates themselves, according to Times Higher Education’s poll, consider that it tarnishes the prizes’ lustre to at least some extent.

So what is the explanation? One hypothesis is that it takes a genius to do work worthy of a Nobel prize, and female geniuses are much rarer than male ones. An example of this line of thinking is the argument from then-president of Harvard University, Larry Summers, who notoriously opined in 2005 that there were so few women in elite mathematics departments because women, compared with men, rarely have the extremely high level of mathematical talent needed to land such positions. And many have noted that the PCPE fields are mathematics-intensive, so maths talent may be crucial to success.

In his reasoning, Summers appeared to be referring to the Greater Male Variability Hypothesis, originally proposed in the late 1800s to explain why all the geniuses and most of the imbeciles (the term of the time) were male. Men were believed to overpopulate the extremely high end of the talent distribution scale as well as the extremely low end. Even if the hypothesis were true, it would still leave the question of why this was so. But my own research shows that, for maths performance, males are only slightly more variable than females. There is certainly not enough of an excess number of them at the high end of the distribution to account for the tiny number of Nobel prizes in PCPE awarded to women.

A second hypothesis is that people believe geniuses are men, and that keeps women out of PCPE in many ways. In some fields, the top people are considered geniuses, whereas in others they aren’t. We think of maths geniuses, for example, but not psychology geniuses. One 2015 study published in Science (“Expectations of brilliance underlie gender distributions across academic disciplines”) found that the belief among academics in the prevalence of brilliance in their own field correlated negatively, across 30 fields, with female representation.

Stereotypes about gender and brilliance appear early. According to a recent study published in Science (“Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests”), by age 6, girls are less likely than boys to believe that members of their gender are “really, really smart”. Thus, the following cultural beliefs are common: Nobel prizes require genius. Top achievements in physics, chemistry and economics require genius. Geniuses are men, not women. Taken together, it is not surprising that women would be less likely to aspire to Nobel-worthy achievements. Nor would it be surprising if, when they did, they were overlooked.

The most celebrated example of an overlooked woman is Rosalind Franklin, the crystallographer who collaborated with Watson, Crick and Wilkins in discovering the structure of DNA. The Nobel Committee said that she was omitted because she had died and they couldn’t award the prize posthumously. But really? Besides, Franklin is by no means the only example of a harshly overlooked woman.

Nor can we rule out the possibility that some plain, old-fashioned discrimination forms part of the explanation. Even today, women face discrimination and other obstacles to their progress in science. In one 2012 study published in PNAS (“Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favour male students”) scientists from research universities rated the materials submitted by an applicant for a laboratory manager position. All faculty saw the same materials, but half saw them attributed to an applicant with a male name and half saw them attributed to someone with a female name. The male applicants were rated significantly more hireable and competent.

It would be a worthwhile project for the Nobel Committee to look over its past awards to investigate whether female scientists were essential parts of award-winning teams but were overlooked. If they find any, they should take steps to recognise them retrospectively.

Even more crucially, the committee should take appropriate steps to ensure that future prizes are awarded equitably. As even laureates themselves apparently recognise, when there is evidence of unfair treatment of the achievements of exceptional women, even this most prestigious of prizes is tarnished.

Janet Shibley Hyde is Helen Thompson Woolley professor and director of the Center for Research on Gender and Women at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login