In 2008 I was standing at a bus stop in Sunnyvale, California – deep in the core of Silicon Valley – when the guy next to me in the queue began waving his phone around in a studiedly conspicuous manner. Intrigued, I made eye contact and my new friend showed me the wonderful, dazzling tricks that his smartphone (a no-name development model in a generic case) could perform. Pointing the phone down the street, the screen showed the live view of the camera superimposed with the road’s name and the distance and direction to the nearest Starbucks. It seems rudimentary now, but my first experience of augmented reality was startling, and by the following year it was available by default to anyone, anywhere, who bought or leased a new smartphone.

Such is the speed of development in these emergent technologies that it is refreshing to take a step back and a look at some of the ways in which our lives and careers are changing – and will continue to change – at a fundamental level. Happily this volume by Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson offers exactly this opportunity, using their deep knowledge of the business and technology sectors to build a detailed, cogent and conversational guide to where we are and where we are going. The story is warmly and richly told, using footnotes approaching a third of a page in length when things get really exciting, and amply supported by notes, references and links. This book is in many senses a primer, a thorough grounding for the digital warrior in the driving forces of the 21st-century economy.

In naming the book Machine, Platform, Crowd and structuring the text into three sections the authors have given a clear steer to the domains they are addressing. Each represents an area of current innovation and development that is, I believe, under-debated in society at large, and combined they form – in the words of the authors – a “triple revolution”.

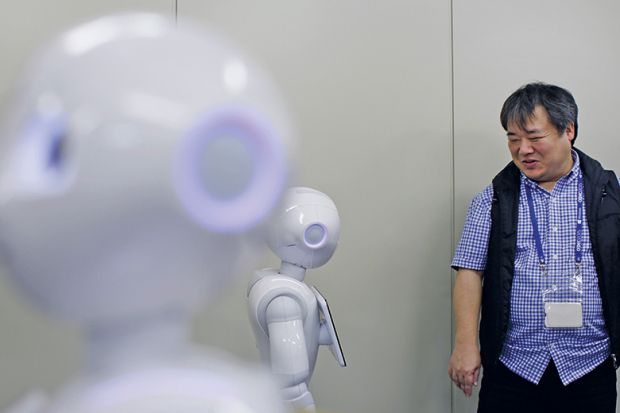

Consider the balance between the human mind and the machine. An accountant with a spreadsheet and an engineer with a computer-aided design system are examples of how we have thought about the essentially supporting role of computing power. As machine learning becomes a major force, however, the balance is beginning to change – to the extent that the question is starting to shift from “What can computers do?” to “What do we still need humans for?” Anyone who thinks their personal contribution is special or un-computable might start to have significant doubts after reading this section. Happily, however, the arguments made by the authors are refreshingly geared towards “How can we use this new power to make things better?” rather than the more traditional dystopian predictions.

The section on product and platform discusses the way in which products are being morphed by the use of new, influential digital platforms. Uber owns no cabs, but it is for many the platform of choice to obtain the product – in this case, a trip between two known points. Uber’s provision is double-sided, as it offers the dedicated enabling platforms to both the client and the provider. Renting a room and finding a news story are also areas where platforms with huge name recognition and global reach (Airbnb, Facebook) are changing our assumptions about the market.

The discussion of core and crowd explores whether, given the pervasive nature of digital services, we actually need anything to be centralised any more. The most sacred tenet of centralisation, other than organised religion itself perhaps, is the management of currency and the tracking of transactions. In the era of Bitcoin, and more importantly the blockchain “un-structure” that supports it through the undirected management of transactions, this can no longer be taken for granted – offering intriguing possibilities for the future structure of both industry and society. This section is particularly well written; it is one of the clearest expositions of the growing potential of blockchain that I have come across.

In many respects this is a book by successful people, about successful people and, to some extent, for successful people. This is not a criticism, merely an observation that I think it is important to make in order to understand the scope of the book. In their acknowledgements, McAfee and Brynjolfsson list a number of visionaries they have consulted, over and above the folk interviewed in the text, who are described as their “favorite alpha geeks”. Having met and interviewed a few of them, I’d suggest that they make up a pretty good cross section of the tech strategy community in the US. However, the risk factor here is that this community can be, in varying degrees, self-referential – in that it exists partly within a bubble of educational, financial and social privilege that is insulated from the broader effects of the strategic decisions the industry makes. However aware they are of their enhanced status – and, to their credit, many of the contributors obviously are – they are in effect isolated from the often brutal regime playing out in the lower reaches of today’s technology-driven economy.

It is hard to overstate the degree to which the triple revolution is bringing about change – especially in the workplace. When, for example, I returned to Silicon Valley a year or so ago, I looked for a taxi at Palo Alto station to take me to my meeting. Memory told me there was a busy rank, but I had to search really hard for it. I finally found a scant few yellow cabs in a shaded corner of the car park, with the drivers killing time by idly playing cards. Digitally mediated hire services had all but dissolved their market in a very few years.

Equally, it is easy to be blinded by the urgent enthusiasms of the tech innovators in the select lunch places off Sand Hill Road (the heart of venture capital territory) who dazzle with their real conviction that the disruptive developments they tout are going to be the next big thing. Some of these developments offer real, positive change – providing new ways to open up opportunities and advance the whole of society. Others merely offer a more cost-effective way of getting more for less from a population of workers already burdened with a gig economy and zero-hours contracts.

Somewhere, I’m sure, there is an app that lets a drone skim leaves from a pool more cheaply than the elderly Spanish guy who fulfilled the role so elegantly at my Mountain View motel, but who will know where to thump the ice machine to make it work when he has gone? When they replace the bandana-wearing ex-Marine in the cut-off denims – who drives the 22 bus from San Jose to Palo Alto – with an artificially intelligent self-driving system, will it still stop late at night on El Camino Real to see if that vulnerable lone pedestrian needs assistance? People offer more to a situation than the sum of their chargeable services – something I’d prefer not to be lost in our digital futures.

The authors believe they are painting an optimistic vision, and do provide pointers to some potential human benefits, but when we disrupt technology we also disrupt lives. We must be careful what, and who, we choose to throw away.

John Gilbey teaches in the department of computer science, Aberystwyth University.

Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future

By Andrew McAfee and Erik Brynjolfsson

Norton, 416pp, £22.99 ISBN 9780393254297

Published 27 June 2017

The authors

Andrew McAfee, co-director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, was born in Illinois and grew up in Indiana. He was an undergraduate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he recalls “enjoying being around really smart, striving people”, and went on to do a doctorate at Harvard University.

This was in 1994, just around the time when the World Wide Web was born, and McAfee soon realised that this would prove “a big deal – one that was going to take our economies and societies someplace they’d not been before. Fifteen years later, in 2009, I came to MIT and started working a lot with Erik. Shortly after that, cars started driving themselves in traffic, machine learning took off, half the world’s adults got online, platform businesses such as Uber started shaking up industries around the world, and many other very interesting things began happening. We were in the right place at the right time to study these phenomena.”

Erik Brynjolfsson, director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy and Schussel family professor of management science at the MIT Sloan School of Management, was born in Denmark but moved to Massachusetts at the age of three. As an undergraduate at Harvard, he says, he “started off in physics and did a lot of maths, but fell in love with economics very quickly. I found that it could combine some of the mathematical rigour I enjoyed with attention to the big questions about what makes society work and how we can make it better.”

After completing college, Brynjolfsson worked at a small start-up building AI systems. Wanting to be at “the intersection of technology and economics…I decided the best way to do that was by pursuing a PhD at MIT…Then, as now, I was convinced that the big improvements in technology portend big changes in the economy. I made it my mission to understand those changes.”

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Apps are taking us places, fast

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login