As a board member of Google and Cisco, you’d expect John Hennessy to know a thing or two about future digital trends.

But the Stanford University president’s prediction to The New Yorker four years ago that a “tsunami was coming” in relation to technology’s impact on higher education appears to have been wide of the mark.

The invention of the massive open online course (Mooc) is “not the kind of revolutionary thing I think people were hoping for. It’s not a disrupter,” Hennessy tells Times Higher Education, adding that the development of online education in general still has a long way to go before it is in a position to challenge traditional campuses.

“We’re very good at concluding that we’ve found the silver bullet before we’ve done the test to determine whether it really is a silver bullet,” he admits.

The term Mooc was coined in 2008, but it was 2012 that The New York Times dubbed “the year of the Mooc”. That was the year that Mooc providers Coursera, Udacity, edX and FutureLearn were all launched – the former two by Stanford academics (see 'The future is...still downloading', below).

Class Central, a website that aggregates Mooc course listings, estimated earlier this year that there are now about 4,200 Moocs offered by more than 500 universities. Last year, 35 million students signed up for at least one of them: up from an estimated 16 to 18 million the previous year.

But despite their consistent growth, the quality of this type of course – in which students typically receive little, if any, personal interaction from academics, and class sizes are in the thousands – has long been questioned. A 2013 study found that the average completion rate for Moocs is less than 7 per cent, and Hennessy does not “have any interest in technology where the completion rates are as abysmal as they’ve been [with Moocs]”.

Nor have the hopes that disadvantaged students from poor countries would swarm to Moocs like bees to honeypots been realised; studies suggest that the majority of current Mooc students are white males with a bachelor’s degree and a full-time job.

In his memorably titled 2014 paper, “With a Mooc Mooc here and a Mooc Mooc there, here a Mooc, there a Mooc, everywhere a Mooc Mooc”, Robert Zemsky, chair of the Learning Alliance for Higher Education at the University of Pennsylvania, says of the model: “They came; they conquered very little; and now they face substantially diminished prospects.”

So if Moocs aren’t the future of higher education in the digital era, what is?

Hennessy – a computer scientist by training – sees most promise in the flipped classroom model, in which students watch video lectures at home and class time is devoted to discussions and interactive problem-solving – provided that class sizes are “small to moderate”.

“We see some pretty good data, both anecdotal and experimental…that really demonstrates that [flipped classrooms] work essentially as well as conventional settings,” he says. “So you can imagine a situation where you use a flipped classroom structure but the person leading the interactive session doesn’t necessarily need to be the master teacher any more. [The instructors] need some skills but perhaps not those necessary to create an enticing set of lectures.”

Another crucial advantage of this model, Hennessy says, is that it reduces the cost of running classes by about 15 per cent. “That’s the first significant reduction we’ve had in the cost of higher education without an accompanying reduction in quality,” he says.

The “question is how to blend” this model into a degree programme that allows all students to reach their potential, he adds. “We’re still doing experiments…We started [off] saying: ‘Learning’s very simple.’ It’s not very simple: it’s very hard. People do it in different ways. One student is good at getting it from a video, another is good at getting it from a book. Another needs more hands-on, one-on-one [tuition] to really master a concept. That’s what we’ve learned.”

In the absence of digital silver bullets, the key challenge for widening accessibility will remain making sure that lower-income students are able to pursue on-campus degrees. To that end, Hennessy sees increasing financial aid as one of the proudest achievements of his 16-year presidency, which comes to a close at the end of August. Stanford students with an annual family income of less than $125,000 (£94,900) no longer have to pay tuition, while those with family income below $65,000 do not pay for on-campus accommodation either.

“That’s done a lot for affordability and accessibility for not only lower-income families but even middle-income families now,” he says.

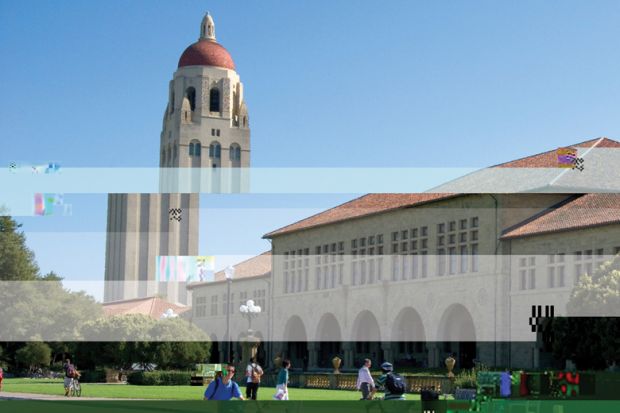

Described as the “godfather of Silicon Valley”, Hennessy has worked at Stanford for nearly 40 years. That epithet, coined by entrepreneur Marc Andreessen, reflects Hennessy’s personal connections to many important high-tech companies: in addition to his Google and Cisco links, he is also founder of MIPS Computer Systems and network communications company Atheros. But it also reflects his role in shaping the development of his students, who are drawn to Stanford as much by its Silicon Valley location as by its prestigious reputation. Many go on to launch businesses of their own; the founders of Google, Instagram, Snapchat and Yahoo are all Stanford faculty and alumni.

It’s an impressive roll call, but does Hennessy worry about Stanford being known only for producing tech entrepreneurs, while competitors such as Harvard University are seen as all-round elite universities?

Hennessy’s response is that Stanford’s ability to forge effective interdisciplinary collaborations – which he has worked hard to build up – is a key advantage. For instance, he says, “We have active collaborations between the business school and the school of education. Bringing the two together can produce a person who has the ability to possibly walk into an urban school district that’s failing, bring the management skills from their business school training, their knowledge about education from their education school training, and do something remarkable. I think we’re particularly well suited to do that versus virtually any other institution.”

Meanwhile, Hennessy has invested a lot in Stanford’s arts provision, as part of his commitment to produce well-rounded graduates.

“Stanford was not at the same level as its peers in those fields and by building facilities and hiring faculty we’ve really transformed it,” he says. “We think it’s important because the arts are the home of creativity and ingenuity and new approaches to things, and I think they provide an opportunity to engage a different part of people’s brain.”

Leadership has been another key area of focus for Hennessy’s presidency. About 10 years ago, the university established a leadership academy for staff, involving one-on-one coaching and team problem-solving. More recently, in March this year, it launched a $750 million scholarship programme with the goal of turning graduate students into future world leaders. The Knight-Hennessy Scholars programme – which Hennessy will run when he steps down as president – was launched with a $400 million donation from Philip Knight, founder of Nike and a Stanford alumnus. This is a further example, Hennessy thinks, of the ways Stanford’s pre-eminence in interdisciplinarity will come into its own.

“We like to think of this notion of ‘T-shaped people’ – people with depth in one area but an ability to collaborate and work with others,” he notes.

Hennessy believes his leadership at Stanford has benefited from his own business experience. He cites Cisco as the company that helped him understand that “universities were doing a very poor job of training their own leaders for future education roles”, while Google helped him master “inventing the future” and “thinking outside the box”.

He also thinks that Stanford constitutes a “Silicon Valley model of a university”, characterised by its relatively flat management structure. “We used to say there are no more than four levels between [senior managers] and anybody in the [university]. Now there are probably six. But anybody…can come and see the president if they really feel they have something important [to say].” A notable recent example was when a student asked him if he would make a video in support of his campaign for election as the university “tree” – the mascot for its athletics teams – on a public service platform.

Universities can also learn from industry when it comes to making “tough decisions”, Hennessy believes. His experience of laying off staff at a start-up company was invaluable, he says, when it came to making cutbacks at Stanford in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, allowing him to achieve a 15 per cent reduction in the budget within 12 months.

Meanwhile, funding for public universities in California fell by 27 per cent between 2008 and 2012, and still hasn’t recovered to pre-crisis levels. One of the institutions that has been hit hardest is the University of California, Berkeley, whose chancellor, Nicholas Dirks, said in a memo to staff earlier this year that the institution faces “a substantial and growing structural deficit”, leading some to question whether it can remain a leading research institution.

But Hennessy denies that Stanford is rubbing its hands at its public neighbour’s travails. “Any small advantage that might be gained that way would be overwhelmed by [the] disadvantage of seeing an incredible school like Berkeley be diminished,” he says. “The system that’s been created in Silicon Valley is much bigger in terms of its needs for talent than Stanford could ever provide solely.”

Returning to the theme of technology, he remains convinced that, Moocs or no Moocs, it offers the best hope of keeping higher education sustainable.

“If you look at the threat to most universities, it’s that their cost model currently grows faster than their revenue model. So now the question is, can you find a way to introduce technology and help reduce your cost growth?” he asks.

He is sure this will be accomplished eventually. “But we have to understand how to deploy technology well,” he adds.

The future is...still downloading

The hype around massive open online courses “didn’t quite get it right”, admits Rick Levin, chief executive of Coursera, the world’s largest Mooc provider. The idea that internet-based learning would swiftly displace traditional universities, and that a selection of online certificates would replace an undergraduate degree, was “a mistaken idea from the beginning”.

But the economist, who spent a record 20 years as president of Yale University before stepping down in 2013, still believes that Moocs can have a transformative impact on higher education: it’s just that the revolutionary scenario predicted by so many might take a “couple of decades” to become a reality.

Coursera has accrued 18 million users worldwide since it was founded in 2012 by two Stanford University computer scientists, Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller. It currently has more than 1,000 courses open for enrolment, delivered by more than 140 educational institutions, including many prestigious institutions within the US and beyond.

Levin tells Times Higher Education that Moocs are already having a significant impact in the realm of professional development, with many of Coursera’s existing courses focusing on areas such as business, computer science and data science. But the company has also been expanding into fields such as arts and humanities and language learning.

The natural next step, says Levin, is the development of online-only postgraduate degrees. Earlier this year, Coursera started offering an MBA and a master’s of computer science in data science from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, and it is likely that more professionally focused master’s degrees will follow. Tuition fees on these courses stand at about $20,000 (£15,140), significantly cheaper than the on-campus equivalent. “I think more people will find it convenient to take these degrees online rather than in school,” says Levin.

The inevitable next question is whether students will be able to study for undergraduate degrees via Coursera. Levin thinks this will happen. He acknowledges it could inflict damage on “middle- and lower-tier institutions”, but adds, “I don’t see that coming for quite a while yet”.

Levin was a proponent of online education long before he took up his role at Coursera in 2014. He pioneered the development of online education at Yale, in partnership with Stanford and the University of Oxford, and went on to set up Open Yale Courses, which offers free access to introductory courses taught by the institution’s academics.

For leading universities, online courses will serve mainly to “magnify their impact”, Levin believes. “Now, Yale professors, instead of teaching a 15-person seminar three or four times a year, can teach 6,000 people in one sitting. Some Coursera teachers teach more people in one class on Coursera than they teach in their entire career on campus.”

The development of paid-for online degrees represents an evolution of the original open model, says Levin, which offers significantly increased coaching and support for students. Coursera has also recently introduced charges of up to $99 for learners who want to submit assignments on a number of its Moocs. Students who do not pay still have access to the course materials, but do not receive a completion certificate.

These developments could be seen to be raising questions about whether Coursera is remaining true to its core mission, to provide “universal access to the world’s best education”. But Levin highlights that more than 100,000 students who could not afford to pay for certification had their fees waived last year.

As for Coursera’s impact in the developing world, around 55 per cent of the students enrolled on its current Moocs are from developed countries – although that proportion is declining. A University of Pennsylvania survey of students on the institution’s first 32 Coursera Moocs, published in 2014, found that nearly 80 per cent of learners already had a bachelor’s degree and 44 per cent had a higher degree, leading the authors to conclude that “the individuals the Mooc revolution is supposed to help most – those without access to higher education in developing countries – are conspicuously underrepresented among the early adopters”.

Levin points to research by Coursera staff and US academics, published last year in the Harvard Business Review, which found that learners without degrees in developing countries reported greater benefit from their courses, in educational and career terms, than the more privileged students. “We’re finding really very heartening results…It would be great if we could see more learners in developing countries without a college education, but we are certainly having a disproportionate impact on people of that type,” he says.

If Moocs are to have the transformational impact that Levin desires, the key issue of retention will also have to be addressed. It has been observed that Mooc completion rates of, on average, 6.8 per cent, are only slightly higher than the dropout rate for the UK higher education as a whole. Levin argues that this is an unfair comparison, because many people sign up to Moocs, typically free of charge, to explore the course materials with no intention of gaining certification at the end. A much fairer comparison, he says, would be to look at the completion rate for users who complete the first week of a programme and say that they intend to stay the course. On this measure, Coursera’s completion rate is in the “mid-double digits” – but Levin accepts that it needs to improve further.

“We are constantly striving to improve the quality of our courses, to pay attention to where people drop out,” he says. “If people are getting through the first two weeks and then dropping off, there is something wrong with that part of the course. Completion rates have been rising steadily, especially over the last few years, as we focus on that.”

It is clear that continuing innovation will be needed if Coursera is indeed to live up to the initial hype surrounding Moocs. But, despite launching many initiatives at Yale, Levin admits that the trial-and-error process of evolving an internet start-up is a “new experience” for him.

“At Yale, with [its] extraordinary reputation, even with ambitious initiatives there was always time to bring constituencies on board to ‘de-risk’ major changes before we launched them,” he says. “We don’t have that luxury in a start-up; things move fast and we have competition. We need to try things all the time and, if things don’t work, we have to reverse course and try something else.”

Chris Havergal

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: The future is...still downloading

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login