In the late 1970s, Marguerite Dennis was a young admissions officer at Georgetown University in Washington DC. At the time, Iranians were the most populous group of international students on campus.

Then came the Iranian Revolution in 1979. “One day the Iranian students were gone, all sent home. I never forgot the lesson,” she recalled on her blog last year.

Dennis, who is now a higher education consultant, told Times Higher Education that she has been warning for four years that something similar could happen – albeit more gradually – regarding Chinese students on Western campuses. “College admission and recruitment officers should get prepared for the time when the number of Chinese students decreases,” she warned in the same blog posting.

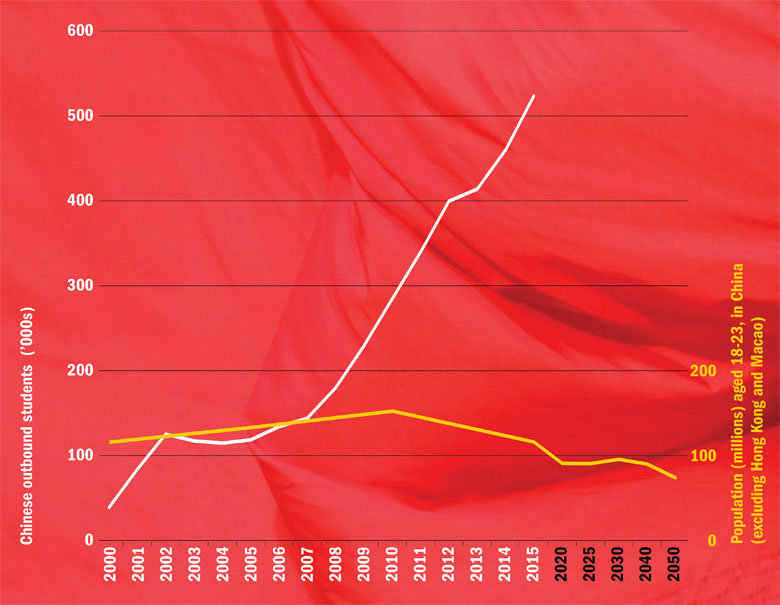

The volume of Chinese students choosing to study abroad is huge and still rising. In 25, more than 500,000 went overseas: a 13-fold increase since the turn of the millennium (see graph on Chinese student growth, below). In a report published last year, the Higher Education Funding Council for England revealed that there are almost as many Chinese as UK students entering full-time taught master’s programmes. The former accounted for 25 per cent of all entrants in 2013, while the latter account for 26 per cent, according to the report, Global Demand for English Higher Education.

This has provided a welcome source of income for many Western universities, but it has also made them vulnerable if the conveyor belt slows down, and there are three reasons why that may soon happen: an ageing Chinese population, a slowing Chinese economy and an increasingly oppressive political environment that sees a Western education as a threat.

The most predictable part of this equation is demography. According to the United Nations Population Division, the number of Chinese people aged 18 to 23 is likely to decline by more than a fifth between 2015 and 2020. It is then expected to stabilise until 2040, and then drop by another fifth by 2050 (see graph on Chinese student growth, below).

“At current rates of higher education growth and demographic transition, there will be a university seat for every child in China by 2030,” potentially sapping demand for foreign education, warns Establishing a Presence in China: a report released earlier this year by the Observatory on Borderless Higher Education.

It points to Japan, whose booming economy in the 1980s prompted many foreign universities to “rush in” to set up branch campuses. A subsequent decline in college-age students in the 1990s and 2000s saw nearly all the campuses close – alongside many domestic institutions.

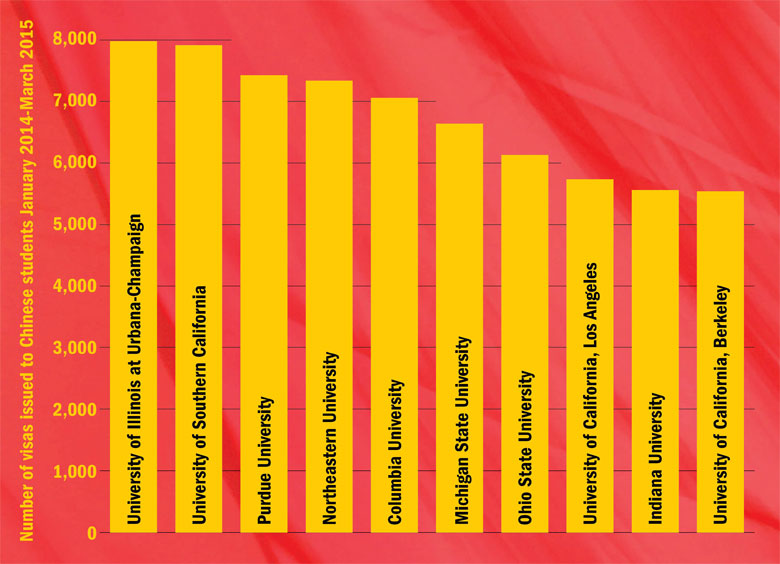

US universities most dependent on Chinese students

Source: Foreign Policy magazine

But Shen Yang, minister counsellor for education at the Chinese Embassy in London, doubts that Chinese demographics will have a significant impact on the number of Chinese students studying abroad. “Every year there will be more than 400,000 Chinese students going out to pursue studies abroad, whereas the Chinese universities’ annual intake is 7.5 million. So the proportion of students pursuing studies abroad is very, very small,” he told the UK-China Education Policy Week 2016 conference, hosted in Beijing by the British Council, in March.

“With further development of China’s economy and also with the societal value system of China – families have always attached huge importance to...education – the family will do everything to help and encourage their kids to pursue studies, not only in China but also abroad,” he argued.

In other words, he thinks that rising wealth will more than offset demographic decline. This has held true so far. The UN statistics show that from 2010 to 2015, the Chinese 18 to 23 population has already dropped by nearly a quarter, and yet the number of overseas Chinese students nearly doubled in that period (see graph on Chinese student growth, below). In other words, demand for foreign university education has been so great that it has more than cancelled out a dramatic shrinking of the university-age population.

China’s economic growth is not what it was in the 2000s. Double-digit growth has given way to annual increases of just under 7 per cent if you believe official statistics, or anywhere from about 3 to 6 per cent, going by other indicators of economic performance. This headline gross domestic product figure could be deceptive, however. The government’s plan is to rebalance the economy by giving households more income (one idea has been to raise the paltry interest rates on bank savings) so that they consume more domestically, making the country less reliant on exports. So even if GDP growth stalls, households may have more to spend – and, as Yang points out, the ultimate consumer purchase in China is education.

Moreover, the impact of economic conditions on outbound student flows can be very counter-intuitive, according to Andrew Scott Conning, a doctoral candidate at Harvard’s Graduate School of Education and author of the Observatory on Borderless Higher Education report. If China’s economy continues to motor ahead in the medium term, this could make many students less inclined to study abroad because of a wealth of opportunities in China itself, he argues. Paradoxically, economic instability could create an incentive for Chinese families to have someone “on the outside”; having a relation with experience in the West can be part of “a larger family strategy, where it keeps its [emigration] options open”.

Complicating matters even further is the future of China’s currency. The number of Chinese students coming to the UK only really began to take off after a big reduction in the value of sterling after the financial crisis. But last August, a yuan devaluation – which makes foreign study more expensive for Chinese families – spooked markets. Many expect the currency to drop further, although recently those betting on future devaluation have suggested that this may take longer than they previously thought.

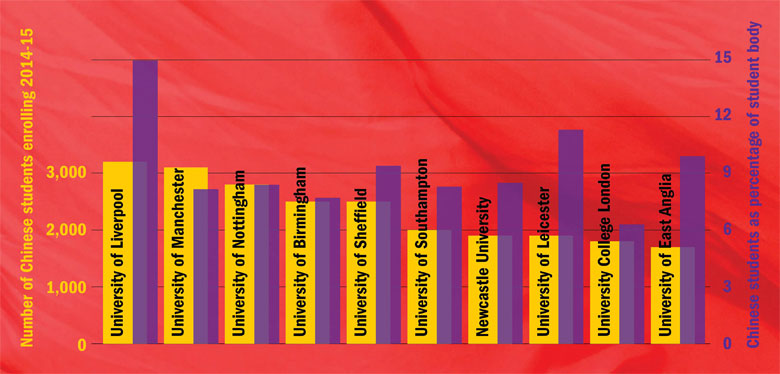

UK universities most dependent on Chinese students

Source: British Council, as quoted in the China Daily newspaper, and the Higher Education Statistics Agency

There are still plenty of families who would like to send their children abroad “but can’t yet afford it”, says Dali Yang, a professor specialising in Chinese politics at the University of Chicago’s department of political science. An economic crisis or major currency devaluation could force some families to reconsider their plans, but many have already “squirrelled away money” to cover the costs, he argues. His sense is that for the “foreseeable future” – by which he means the next four or five years – “these trends will continue to be very robust”. However, “the speed-up may moderate somewhat”.

What about tougher competition from better Chinese institutions? Might Chinese students realise that there are perfectly good universities in their home province and decide to save huge sums of money by staying put?

Matt Durnin, head of research in China for the British Council, believes that better domestic quality will indeed cut the need to go overseas. Although university rankings struggle to directly measure teaching quality, there are now substantially more Chinese universities in China’s own ranking, the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Academic Ranking of World Universities, his research shows. And citation analysis suggests that Chinese research has improved markedly in recent years.

That said, the massive expansion in university places during the 2000s has pushed down the earnings premium for domestic graduates. Those entering the labour market earned 27 per cent less in 2008 than they did in 2002, according to a study by British and Chinese academics released in May, titled “China’s expansion of higher education: the labour market consequences of a supply shock”. As in the UK and other developed countries, many more graduates are being forced to take jobs that were previously the preserve of those with only a secondary school education.

But those returning from abroad are discovering that their degree is yielding diminishing returns too. According to the Chinese economics magazine Caixin, about half of these “haigui” – sea turtles, returning to their place of birth – with foreign bachelor’s degrees earn less than 5,000 yuan (£544) a month when back in China – although this is still double the average starting salary of 2,443 yuan among all Chinese students who graduated in 2014, according to a Peking University survey. Internet users have started calling those who have failed to find jobs on their return “haidai” – seaweed – according to Caixin, which also quoted employers complaining of an oversupply of foreign degrees. Whether overseas study is worth it, then, may come to depend on whether domestic or foreign degrees decline in value more rapidly.

The value of a foreign degree could also be eroded by politics. There has been a shift towards a stricter form of authoritarianism under Xi Jinping, who became president in 2013. In particular, “Western ideas” have come under attack. At the beginning of 2015, Yuan Guiren, the education minister, pledged to ban university textbooks that promote “Western values”. Last December, The Wall Street Journal reported that the authorities were clamping down on English language preparatory curricula for studying abroad.

Chinese student growth

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics of China, British Council, United Nations

There are still no actual restrictions on university students going abroad – unsurprising, given how common this is among elite families (Xi’s daughter attended Harvard University). But if the economy slows and the party dials up xenophobic rhetoric as a distraction, it is unclear how things could escalate. “In the next phase of the new [more authoritarian] China it may not be beneficial to have a degree from an international school,” Dennis has argued.

However, Chicago’s Yang is more sanguine. Students who go abroad for higher education have, in some sense, already been ideologically “inoculated” by propaganda in the school system (see 'The ides of Marx: interpreting ancient Rome' box, below), he says, and returning students tend to be “pretty neutral” politically. Secondary education is the more important ideological lever for the party, he thinks: “That’s where they have been much more conscious in not letting foreign players play a bigger role.”

So what, if anything, can Western universities do to guard against a future without such an abundance of Chinese students? The British Council’s Durnin warned in an analysis last year, titled By the Numbers: Inward Mobility in 2015, that there are “no straightforward strategies for hedging against shocks in the China market. While several emerging economies show long-term promise, there is no ‘next China’ on the horizon.”

Instead, universities may need to do more to make themselves attractive to Chinese students. There is no shortage of complaints to be addressed. Problems facing Chinese students overseas – a lack of social integration, poor English, weak critical thinking and a tendency to produce poorly referenced essays that land them in hot water for plagiarism – are well documented.

A recent Wall Street Journal investigation painted a bleak picture. On the one hand, it found Chinese students so surrounded by their compatriots that the most English they spoke all day was to order a burrito. On the other, academics were frustrated by having to modify their lectures and complained that Chinese students often lacked analytical or writing skills.

Rahul Choudaha, head of higher education consulting firm DrEducation, is scathing of universities that have failed to properly take care of their Chinese charges. Over the past decade, the “lure” of the money Chinese students bring “was so appealing that a whole industry of test prep, admissions consulting and recruitment agents in China emerged to ‘package’ applications and make them admissible to universities”, he says.

“However, ‘packaging applications’ to make an individual look good is very different from actually creating skill sets for success in a new cultural environment,” he says. As a result, Chinese students arrive in the West not only lacking good English but also with completely different cultural assumptions and communication styles. Universities have failed to support them consistently, so “it is not surprising that Chinese students stick together as their only support system”. This situation is only likely to get worse: the growth of students who need university support services “will outpace growth of academically prepared and self-directed students”, he predicts.

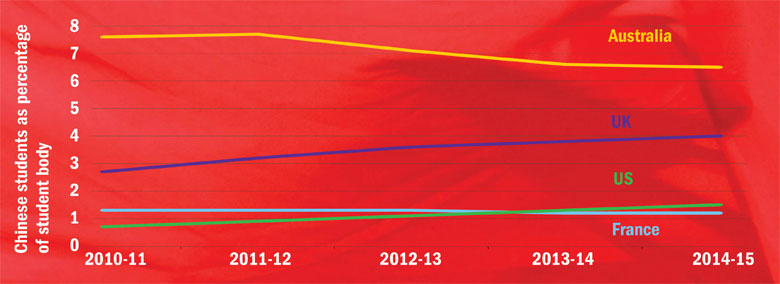

Countries most reliant on Chinese students

Sources: Higher Education Statistics Agency (UK), Institute of International Education (US, France), National Center for Education Statistics (US), Department of Education and Training (Australia)

“Yes, it’s a challenge,” says Eric Furda, dean of admissions at the University of Pennsylvania, of the difficulties of integrating Chinese students on campus. “You have to have a deep understanding of what you’re trying to achieve,” he says, such as what degree of assimilation is desirable.

Pennsylvania’s accommodation policy is to randomise where students stay in their first year. “Early on, you want to shake it all up,” he says. Additionally, in an attempt to create something of a common cultural hinterland for students, the university, like many other US institutions, asks every freshman to read a book, watch a film or study an artwork before they arrive on campus (this year’s choice was Citizen Kane). The students are then put into small groups to discuss their reactions and write reflective pieces about them. “You can’t legislate this, or dictate this, but you’re trying to create these spaces of opportunity” for interactions between students who might otherwise never speak, explains Furda.

But even this does not necessarily create lasting, mixed friendship groups, he admits. In the second year, when students are able to decide where to live, students often retreat into their “comfort zones”.

Despite all the clouds on the horizon, China remains a big, largely untapped market for some universities. Geoff Smith, senior deputy vice-chancellor at arts-focused Falmouth University in southwest England, says that the institution has been “much more active in China in the past few years”, targeting high schools attached to China’s top arts universities.

The push is bearing fruit – this year, applications have at least doubled, Smith says. He cautions that this is from a low base, and that it remains to be seen whether applications will translate into enrolments. Still, the feedback from China is that applicants and families increasingly believe that there is “huge scope” for the creative industries to “sustain a very credible career”.

“If you’re a fantastic animator, you can get work anywhere in the world,” Smith argues.

This is a sign of a broader shift away from the more utilitarian subjects traditionally favoured by Chinese students abroad, says Chicago’s Yang. “In the early days, Chinese families…wanted their kids to do something just to have more earning power,” he says. “But as China has risen in wealth, a greater percentage are choosing areas of interest” for their children.

In future, then, Western universities may have to win over not just Chinese parents but the applicants themselves too.

The ides of Marx: interpreting ancient Rome

Marxism may be only a shadow of its former self in Western education, but it is alive and well in Chinese school textbooks.

The country’s secondary school curriculum provides an insight into the often propagandised history, philosophy, politics and economics that Chinese students are exposed to before they arrive on Western campuses.

The Communist Party’s line on 20th-century history is well known. But perhaps less widely understood is the approach it takes towards older periods of history, and how deeply Marxism still pervades the worldview students are taught, despite its abandonment by China’s economic policymakers more than 30 years ago. History books are littered with terms such as “Western capitalist parliamentarianism” and students’ introduction to ancient history begins with a preface explaining the tenets of historical materialism.

Marxist foreshadowing is even present in a chapter on ancient Rome. “During modern history, capitalists used Roman legal ideas to create a legal system that would protect their own interests. They used it as a tool to overturn feudalism and advance the development of capitalism,” students are told.

Chinese nationalism also pervades the history curriculum. “The Chinese nation is the world’s most ancient civilisation. China is one of the world’s four great civilisations, has an unbroken history and possesses great vitality,” one passage says. In a preamble to a chapter on ancient China, students are asked to use “geography, history and politics to understand why centralisation was inevitable” – an extremely sensitive subject given Beijing’s current difficulty controlling Taiwan, Hong Kong, Tibet and the far western province of Xinjiang.

In economics, although globalisation is presented as a process with the potential to be a force for good, the fact that rich countries set the “rules of the game” for their own benefit means that it is driving increasing economic polarisation.

On religion, the message is blunt. “Explain why the idea of creation does not fit with objective reality,” students are told in the textbook on “life and philosophy”. “Everything in the natural world formed and developed according to its own law,” it explains. “The universe has no god.”

Whether students actually believe all this is a moot point. But they will arrive in Western lecture theatres having been exposed to a very different approach to education from the one their domestic classmates are used to.

David Matthews

Getting to know you?: friendship difficulties

Are UK universities dynamic multicultural platforms or glorified international transportation hubs?

For my recent MSc, I examined the friendship patterns of postgraduate home and international students at the University of Bristol. More than three-quarters of nonChinese participants perceived Chinese students to be cliquey and 62 per cent of Chinese students had no British friends – compared with 15 per cent of non-Chinese international students.

Language is clearly an issue. While 97 per cent of the Chinese respondents described their English as understandable, 93 per cent of non-Chinese postgraduates rated Chinese students’ spoken English as “below average” or worse. But do Chinese students avoid British social settings because of their difficulties with English, or are they unable to acquire decent conversational English because of insufficient socialising? Only seven of 45 Chinese respondents had been to a pub more than three times, for example.

Chinese students’ reluctance to engage in peer discussions may also make them appear uninterested in socialising. Meanwhile, British students are stereotyped by international students as unapproachable, and it is interesting to note that 12 per cent of British postgraduates had not even made any new friends among their compatriots since their programmes began, compared with only 4 per cent of Chinese students.

Why else might Chinese postgraduates be less motivated to build local ties? One possible reason is that they can remain in the UK for only four months after their period of study ends – although the same applies to all non-European Union students. In addition, they are attentively looked after by Chinese diaspora associations and business circles, which are very active on social media.

Universities should not attempt to glue different nationalities together in order to “look multicultural”. But when students do want to get to know each other better, they should have opportunities to do so – and not just of the sit-drink-and-talk type. International offices in UK institutions should facilitate the integration of international and local students throughout the academic year. Reading groups and academic festivals, for example, would be welcomed by research postgraduates, while cultural exchanges and organised trips are attractive to taught postgraduates. The University of California, for instance, hosts an annual walking festival on every campus, which had nearly 5,500 participants in 2013.

The UK has more international students than any other European country, yet the largest international student festival happens in Trondheim, Norway. Mostly relying on student volunteers, it holds not only cultural events such as concerts and art exhibitions, but also a “dialogue group”, which aims at building intercultural understanding through workshops and debates.

The UK universities that continue to be successful in recruiting international students will be those that recognise that recruitment is just the beginning of meaningful multiculturalism.

Lin Ma is a freelance researcher. She has an MSc from the University of Bristol in East Asian development and the global economy. She can be reached at m.lin.2012@bristol.ac.uk

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Unpredictable currents

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login