UK academics and professional and support staff inhabit “two parallel universes that have little point of contact”.

That is one of the major conclusions to be drawn from the third annual Times Higher Education University Workplace Survey, according to Yiannis Gabriel, chair in organisation studies at the University of Bath and one of the designers of our inaugural survey in 2014.

Over the course of several months in 2015, almost 2,900 higher education staff, of all ranks and roles, from nearly 150 institutions across the UK gave us their views on a wide range of employment issues.

As well as answering specific questions, respondents also submitted almost 4,000 comments to the online survey, providing further context to many of the important issues raised by the survey.

Download the full results of the University Workplace Survey 2016 (PDF)

Download the full results of the University Workplace Survey 2016 (Excel)

All survey participants were verified as working in UK higher education institutions, with 49 per cent identifying themselves as academics and 51 per cent stating that they held professional or support roles. As well as the deep gulf between the two categories of staff in many areas of working life, the survey also highlights that:

- Most university staff find their jobs rewarding, but most academics feel overworked, exploited and ignored by management

- A majority of staff feel satisfied with pay, conditions and professional development opportunities

- Half of academics are worried about redundancies related to metrics-based performance measures

- Half of academics think that their institutions have compromised undergraduate entry standards as competition for students has increased, and half feel under pressure to award higher marks.

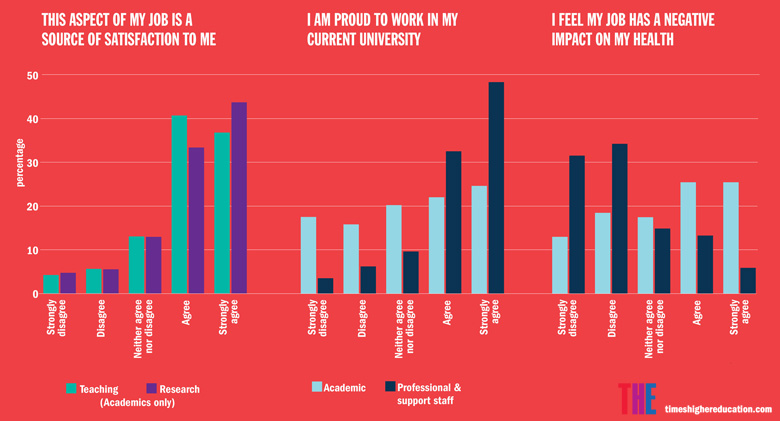

Overall, the vast majority of higher education staff are happy in their jobs. Some 80 per cent of university employees state that their work is a source of satisfaction – roughly the same proportion as in our previous two surveys. In addition, 70 per cent agree that their job is “rewarding”, while 87 per cent enjoy working with their immediate colleagues.

“In moments of tiredness or frustration being surrounded by 10,000 (mostly) young people who are optimistic and keen to learn is a pick-me-up and a privilege,” remarks one senior administrator at a post-92 university. A female academic at a Russell Group university also appreciates the “good pay, holidays and working hours”, adding that her institution is “supportive of staff with young families”.

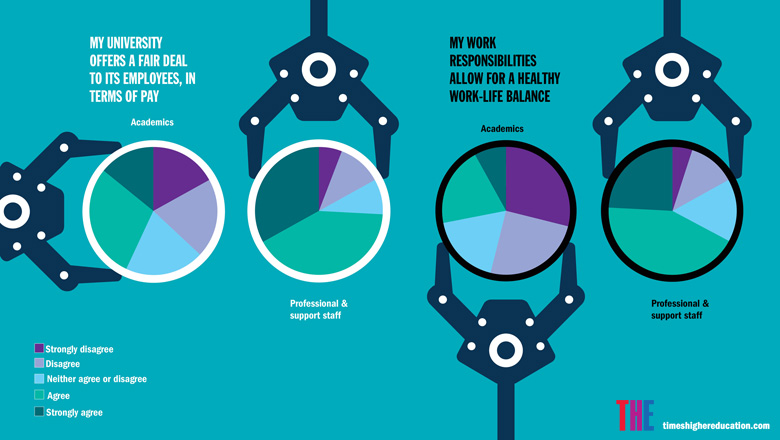

Job satisfaction levels are slightly lower among academics (77 per cent) than among professional or support staff (84 per cent). But the academic-administrative divide is particularly evident around questions related to pay and working conditions. Just 43 per cent of academics believe that they receive a fair deal in terms of pay, compared with 74 per cent of administrators. (Overall, 59 per cent of respondents are satisfied, against 26 per cent who are not.)

“I am constantly being asked to do more with less, which translates into longer and longer working hours. As a result, the level of compensation is completely incommensurate with the working hours reasonably needed in order to do everything that is demanded,” says a lecturer at one Russell Group university.

On working conditions and other benefits, the chasm in opinion is even greater: only 40 per cent of academics are happy with what their university offers, compared with 80 per cent of professional and support staff.

But the overall figure of 60 per cent is markedly higher than the 42 per cent satisfaction rate found in the overall UK economy, a spokesman for the Universities and Colleges Employers Association points out: “It is encouraging once again to note that the majority of participants believe their institution offers them a fair deal in terms of pay, as well as the sometimes overlooked but very important conditions of service and other benefits.”

The spokesman adds that the survey results should be read alongside Ucea’s own workplace survey, which “confirms that the sector continues to benefit from [having] few recruitment and retention difficulties” and that the “total reward package offered [is] competing well with packages in the private and public sectors”.

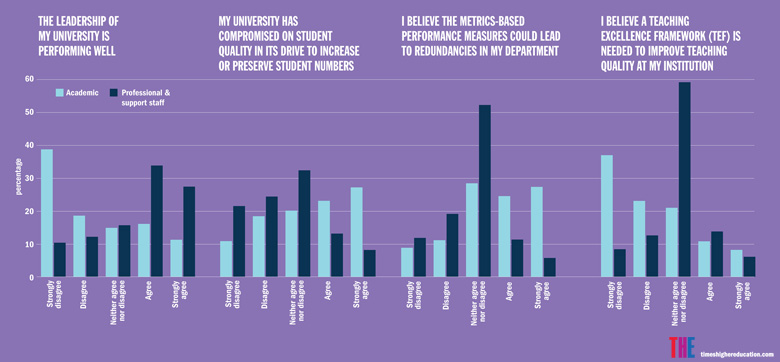

The difference in opinion between academics and professional and support staff is also stark in other areas. Academics are more disillusioned with senior management, for instance. When asked if their university leadership is performing well, only 28 per cent agree, compared with 61 per cent of administrators. Academics are also markedly less likely to be excited about their university’s plans (27 per cent felt this way, compared with 63 per cent of professional and support staff). And Gabriel flags up the fact that only 38 per cent of academics would recommend working at their university, compared with 77 per cent of professional and support staff. He describes such enormous discrepancies as “little short of staggering”.

“Professional and support staff are proud of their institution, and appreciate the environment and conditions of employment,” he says. “By contrast, academics report a substantial degree of stress and considerable dissatisfaction with the leadership of both their department and their institution, and a considerable number are looking to leave their current job.”

Not all academics are entirely dismissive of management efforts. One senior lecturer at a post-92 university in the south of England sees his university’s leadership as “good on the whole”, if sometimes “cringingly corporate in its outlook”.

But on their university’s contribution to the community and society at large, academics are again less positive. While 80 per cent of professional and support staff express approval, only 49 per cent of academics do so. Among the latter is a medical professor at a university in the South West, who says that his institution enjoys an excellent local reputation for “engag[ing] effectively with regional development in many ways, including health promotion and green policies”.

Despite limited enthusiasm for many aspects of higher education, academics still appear to enjoy the core parts of scholarly life. For instance, 77 per cent say that they derive satisfaction from their teaching.

The same proportion also agree that their research is a source of satisfaction, while the proportion that strongly agree with that proposition is even higher (44 per cent, versus 37 per cent). However, two-thirds of academics (67 per cent) also say that they do not have enough time to do the research they need to get ahead – almost four times as many as those who are broadly happy with the time available for research (17 per cent).

The anonymised comments suggest to Gabriel that academics are exercised by three main issues: growing managerialism and associated “market-driven and rankings-driven policies, constant performance monitoring and target setting”; escalating bureaucracy and “standardisation that erodes professional discretion”; and “excessive preoccupation with image and hype: the bullshit factor, where everyone must be a star, world class, cutting-edge and the like”.

He also observes that academic respondents are more likely to strongly agree or disagree with statements, suggesting that those with “more extreme views were more likely to answer the survey than those with more moderate ones”. However, he admits that “the conclusion that malcontents have crowded the survey is not inevitable” and it would need further evidence to substantiate.

Either way, the results of the survey are sure to provide much food for thought for university managers, who ultimately depend on academics to carry out the core missions of their institutions.

Workload and work-life balance

The excessive hours worked by academics are once again highlighted as a major problem by respondents to our survey. Most staff appear to routinely work beyond their contracted hours.

“I love my job and I’m prepared to put in extra time,” says one administrator at a northern post-92 institution, who is paid for 23 hours a week, but “generally work[s] more than 40, often nearer 60”.

However, professional staff are markedly less likely than academics to work beyond normal hours: 57 per cent report doing so, compared with 89 per cent of academic respondents.

Many of those who do so earn little credit. Overall, 44 per cent of respondents say their manager does not acknowledge the extra hours they work. And while 40 per cent say that their graft is appreciated, people with that perspective are unlikely to be academics. Only 21 per cent of academic staff say that their extra hours are acknowledged, compared with 58 per cent of professional staff. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that the 51 per cent of all staff who feel that their university sometimes takes advantage of them rises to 67 per cent among academics.

“I feel unappreciated – I work 100 hours a week and I’m exhausted,” says one senior lecturer at a London university.

“I thought this was my dream job and would stay until I retire, but [the] workload is unmanageable,” adds a lecturer at a research-intensive university in the North. All her colleagues are also working “unspeakably long hours”, with one even having worked on Christmas Day.

The 68 per cent of academic respondents who say that they work too much is two percentage points higher than in our 2015 survey (the 30 per cent figure for professional staff is the same as last year).

“Staff are expected routinely to work Saturdays without any additional remuneration,” reports a social sciences lecturer at a Midlands university.

“I don’t think I can realistically keep this up until retirement without making myself seriously ill from stress,” adds a lecturer at a Russell Group university, who is considering a career change.

Indeed, just over a third of all respondents (35 per cent) say that their job has a negative impact on their health – which rises to half (51 per cent) among academics.

“Staff are being worked to their limits and the university is taking advantage of the workload models, which in themselves are horrendous tools to make us work even more,” says a professor in an arts and humanities subject at a northern Russell Group university.

“Unmanageable workloads, poor work-life balance and the associated stresses are unsurprisingly top of the complaints list for lecturers again this year,” comments Sally Hunt, general secretary of the University and College Union. “Survey after survey identifies increasing workloads and poor management as real problems for our universities, yet nothing is done to address the issues. Increasing workloads, higher rates of casualisation and diminishing support are not the way to deliver the world-class system that leaders and politicians say they want.”

However, our survey does not paint an unremittingly bleak picture. Some 56 per cent of all respondents say that the workload assigned to them is “reasonable” – almost twice the 32 per cent who feel their workload to be unreasonable. That former proportion increases to 72 per cent for professional and support staff, compared with 38 per cent for academics.

Staff are also more likely than not to say that their university cares for the well-being of its workforce (49 per cent agree that they do, against 36 per cent who disagree).

“Having had a couple of very hard years personally, I’ve been blown away by the unconditional support I’ve received from my department,” says one manager at a northern post-92 university.

“Having worked in the private sector for years, I am constantly surprised by the caring and paternalistic attitude of the university, right from the vice-chancellor down to the cleaner,” adds an administrator at a medium-sized research-intensive in the South East. “I am always shocked by people who think that the university is a bad employer and [is] out to get them in some way – people [don’t] realise how good they have it.”

Gabriel believes that the huge gulf between the perspectives of academic and professional and support staff in this area can partly be explained by the fact that many of the latter compare their university jobs with earlier employment in other sectors, such as insurance and banking. “They find the terms and conditions of work in higher education far preferable to those in the private sector and are not put off by the managerial styles, bureaucracy or target-driven philosophy of their academic institutions. They enjoy what looks to them like a green, relaxed and pleasant campus atmosphere,” he says.

By contrast, academics perceive a “continuously deteriorating situation, where standards are constantly eroding, conditions of work are dropping and extensive reports of bullying and harassment are not uncommon”.

Nonetheless, our respondents tend to view employer attitudes towards their caring responsibilities in a positive light: the 47 per cent of all staff who say that their university is supportive is more than twice the 19 per cent who feel it is not.

Staff are also more than a third more likely than not to see their job as offering a healthy work-life balance, with 48 per cent overall agreeing that it does, as opposed to 35 per cent disagreeing.

“I have my own spacious office and supportive colleagues, excellent line management and opportunities to work at home, which allows me to work full-time, despite having a young family,” says one female administrator at a large research-intensive university in the South.

However, the views of academics and administrators once again vary hugely on this issue: only 28 per cent of the former say that they have a good work-life balance compared with 67 per cent of professional and support staff. And only 28 per cent of academics believe that their university cares about the well-being of its staff, compared with 68 per cent of professional staff.

Academic standards

After decades of strict controls on student numbers, universities in England are now able to recruit as many undergraduates as they wish.

The end of institutional quotas, which fully came into effect last September, was hailed as a crucial step towards improving social mobility; in the words of the chancellor George Osborne, who announced the plan in 2013, the policy will end the “cap on aspiration”. It is also meant to drive up quality and increase student recruitment competition between universities, but many academics appear to have reservations about their institution’s response to the new admissions landscape.

Half of academic respondents to our survey agree that their university has compromised on student quality in its push to increase or preserve student numbers.

“What happens now is nothing short of criminal – we recruit anybody, no matter how bad they are,” claims one academic at a post-92 university in the North. “We used to have [more than] 95 per cent graduate employment, now it is barely 80 per cent and falling, because of the dross we are turning out. No one seems to care one jot that we are turning out cheats and useless, incapable dolts with top marks.”

Concern is less acute among administrators, of whom just one in five feels the same way.

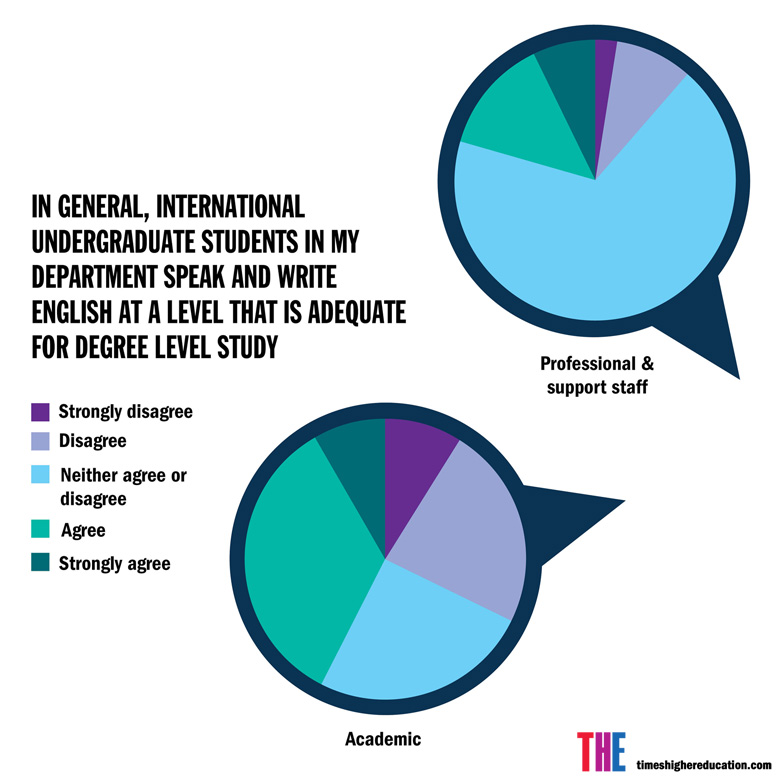

Many academics also believe that their institution has let entry standards slip for international students; one-third say that they do not think overseas students in their department speak and write English at a level that is adequate for degree-level study.

“Now I feel that we just try and get as many students as possible, especially international, and that standards have dropped,” says one administrator at a large northern university.

With most undergraduates in England now paying £9,000 a year, or close to it, just under half of academics feel under greater pressure to award higher marks, against less than a third who do not.

“[My] university is dumbing down courses,” says a science professor at a Russell Group university, adding that this is “not challenging the students and is unfair to the best [ones]”.

“This year, 15 firsts were awarded on [our] LLB course,” reports one senior law lecturer at a modern university in the Midlands. “How is this possible when a redbrick university with straight-A students might award three or four?”

A lecturer at a Scottish university claims that its academics are “told to meet a target of an 85 per cent pass rate routinely, irrespective of student performance or ability”.

Some 44 per cent of academics also say that their workload has increased since the introduction of £9,000 tuition fees, compared with 17 per cent who say it has not.

“I used to love working here, but my workload has quadrupled and staff morale is at rock bottom,” says a senior lecturer at a Russell Group university in the Midlands.

Job security

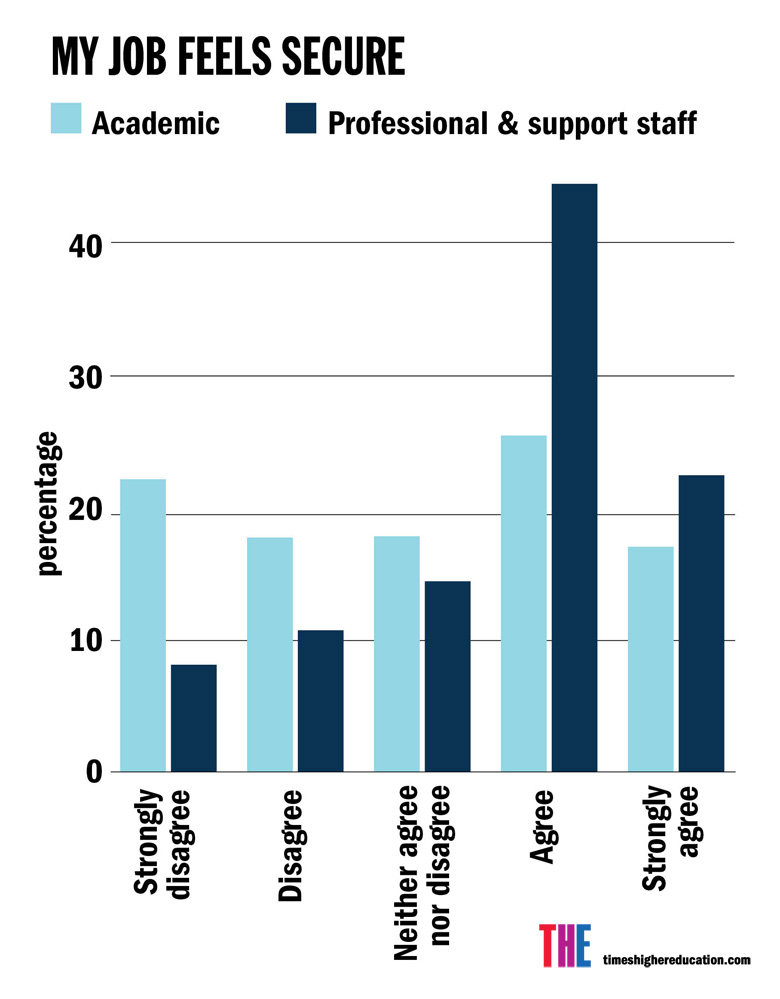

Job insecurity is a key issue for many academics. Overall, 55 per cent of survey respondents feel secure in their jobs compared with 29 per cent who don’t. But, among academics, the latter figure rises to 40 per cent (among professional and support staff, it falls to 19 per cent).

“We have had round upon round of redundancies and the university breaking [its] own redundancy avoidance policies,” complains a long-serving administrator at a Russell Group university. “Workloads have increased significantly as staff who leave are not replaced – it is almost as though the intention is to force people to feel so uncomfortable that they wish to leave.”

As Times Higher Education has reported, there is an emerging concern over the threat imposed by metrics-based performance measures. Just over half of academics believe that these could lead to redundancies in their department.

“University leadership are on record saying they want a high staff turnover and…[pursue] this perverse aim by setting unreasonable personal targets for all academic staff, enforcing them with a new draconian performance assessment system,” one academic at a Russell Group university writes.

Others believe newly introduced targets have had a corrosive effect on departmental morale: “I love many aspects of my university, but the introduction of performance targets for individuals…is antithetical to good scholarship and teaching, to relationship-building and collegiality…and to the overall good of the profession,” says an academic at a large research-intensive northern university.

“We are being set funding targets which, it is widely acknowledged, are impossible for even half of us to meet,” says another academic at a Russell Group university. “The sense among many of us is that this is a first step in a process of [constructive] dismissal.”

The medium-sized Midlands university where one professor works “has become a nightmare within just a year as the new dean of science has introduced metric-oriented, ‘business-like’ criteria of performance within the school. This has been introduced along with direct and explicit threats of dismissal for many members of staff, who became the subject of a ‘research performance review’. My work at my university now feels highly stressful and insecure.”

And a senior lecturer at a Russell Group university complains that “now it is all about metrics. Performance management is really a euphemism for: ‘If we don’t like you, we will get rid of you or bully you until you quit.’”

Listening to staff

The failure of managers to listen to staff views is a major source of frustration for the sector’s workforce, our survey suggests.

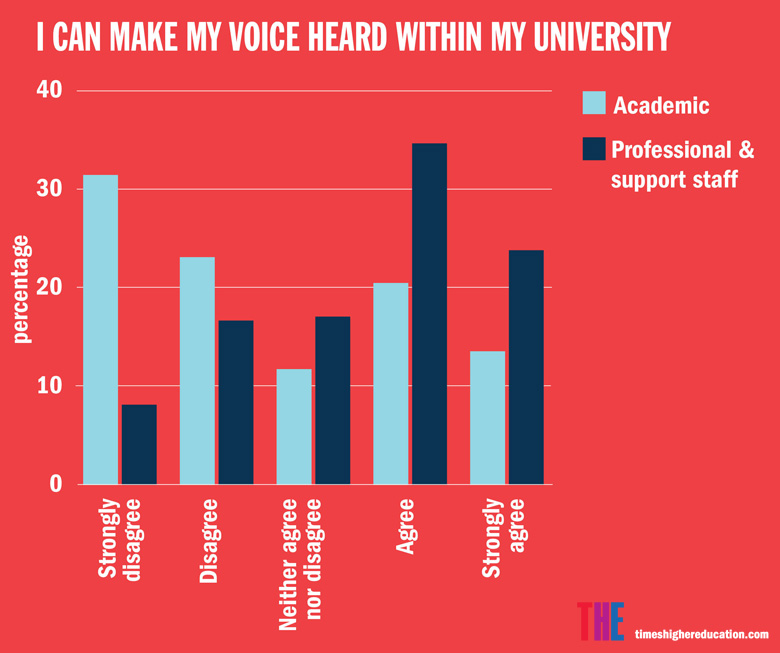

Some 39 per cent of respondents overall, and 54 per cent of academics, say that they can’t make their voices heard within their university. Only 25 per cent of professional and support staff feel the same way, but the comments suggest that the issue has a dispiriting effect on morale wherever it is felt.

“Directives and decrees come down from [on high]…without any consultation or any consideration of the practicalities of implementing them,” states one IT technician at a large university in the North West.

“We get crazy diktats – like they want to take all our printers away,” complains a senior lecturer in science at a Russell Group university. “Nobody bothered to ask us, or we would have told them that we need printers for our [scientific] instruments.”

A senior lecturer at a post-92 university in the South of England claims that the views of academics are not heard by senior management: “Those on the ground, working with students, know what is going on and should be listened to, instead of middle managers who are merely yes-men.”

A senior lecturer at a research-intensive university in London says exercises to engage with staff are a charade. His institution is “adept at pretending to solicit staff opinion on major [issues] affecting staff welfare and infrastructure while refusing to allow [that] opinion to affect final decision outcomes”.

A senior lecturer in social sciences at a Scottish university claims staff are unwilling to speak out against institutional changes. “Most are too scared to say anything beyond grousing with peers and friends,” he says, adding that the “academic senate just rubberstamps the demands of the principal, who attacks anyone who dares question his vision or ideas”.

An early career academic at another Scottish university has been advised by colleagues to “keep my head below the parapet and avoid being noticed by senior management. This kind of environment is obviously not one that could be considered friendly, but it is even more damaging when…students and academics are supposed to participate in a free exchange of ideas and theories,” he says.

However, not everyone is so gloomy. Indeed, 46 per cent of respondents feel that they can make their voices heard: a figure that rises to 58 per cent among professional and support staff.

“The university is making a concerted effort to listen to and engage with staff by arranging breakfast meetings and networking events,” reports one administrator at a North East university.

However, only 34 per cent of academics feel heard by university leadership. One senior lecturer in social sciences at a post-92 university in the South of England complains: “Students are sick to death of being asked for their view on every little detail of the course, but the management never solicit the views of staff.”

Things we like...

‘The “army of administrators” identified by THE [in previous stories] is actually a set of strong support services: the disability, academic skills, careers, counselling and library services who are very good at offering personalised support’

Librarian at a large post-92 university in the North

‘I have been well supported in my new role and relish the challenges that we will be facing over the coming years. For my family and myself, this has been my most positive working experience to date’

Administrator at a university in the North West

‘I feel proud of working for my institution. It cares about the local community, opening up education for students in all circumstances and providing top-class facilities’

Administrator at a post-92 university in the North

‘My current employer is by no means immune from the wider tendencies towards performance management, but it is by far the most sensibly managed, intellectually vibrant and happy place at which I have worked’

Business professor at a medium-sized London university

‘I am impressed by the amount of opportunities for professional development afforded to me. The university has a great graduate internship scheme, which has helped many graduates like myself gain full-time employment and meaningful work experience’

Technician at a large modern university in the North West

‘I like the fact we have students coming from very different experiences and backgrounds – mature students especially are a great source of inspiration to me’

Research fellow at a large London university

‘The university environment is open and supportive, which promotes collaboration. The university is a physically pleasant place to work, with a nice campus and a diverse student body’

Lecturer at a Russell Group university in the Midlands

…and things we don’t

‘Every time I see the senior management team, I long for my retirement. HR view staff as a resource to be exploited, and ultimately, exhausted. The good news is that the students are fine’

Lecturer at a medium-sized university in the North West

‘Senior management within my university are often out of touch with reality, incompetent, lazy, complacent, and unconcerned with fairness to other staff except in so far as this might help them win a prestigious award for the university’

Senior lecturer in social sciences at a London university

‘Never before have I been aware of such an atmosphere of dissatisfaction, frustration at the senior management team and general unhappiness. The belief that we are “all in this together” has rapidly disappeared and I can’t see how the goodwill of staff can be won back’

Administrator at a post-92 university in Scotland

‘The university seems happy to compromise academic standards for vocational accreditation, which puts an industry-accredited underwater basket-weaving degree on a par with STEM subjects and traditional arts subjects, such as history and English’

Senior lecturer at a modern university in the South of England

‘It has become increasingly rare for students to be motivated or engaged by their studies, or to possess what, for me, is an ordinary degree of cultural and academic hinterland’

Professor at a post-92 university in Scotland

‘We currently live under a reign of terror. Senior management seems happy to sacrifice the careers of colleagues in many parts of the university to build a war chest for future expansion in “strategic areas” ’

Senior lecturer at a research-intensive university in Scotland

‘The university seems happy to compromise academic standards for vocational accreditation, which puts an industry-accredited underwater basket-weaving degree on a par with STEM subjects and traditional arts subjects, such as history and English’

Senior lecturer at a modern university in the South of England

Survey methodology

To compile the Times Higher Education University Workplace Survey 2016, we canvassed the opinions of higher education employees from across the UK between September and December 2015 in an online survey.

There were 2,852 respondents. Of those, 1,398 (49 per cent) describe themselves as “academics”, with 1,454 (51 per cent) stating that they work in “professional and support” roles. The gender split is 1,564 female and 1,288 male.

Each respondent was presented with 37 statements about their institution, such as “I would recommend working at my university to others”. They were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the statement on a five-point Likert scale: strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, or strongly agree.

In the table, the total percentages of all respondents who disagree or agree with a question are based on the survey’s raw data. As such, they may differ from the sum of the figures in the table, which have been rounded.

The survey also allowed participants to write comments about their institution in three categories: “things my university does well”; “areas in which my university could improve”; and an open box for any further comments.

To ensure that respondents completed the survey only once, and that they were affiliated to a university, only people with a working “.ac.uk” email address could take part. The owner of each email address could complete the survey only once.

The independent online survey was first developed by THE in consultation with Rob Briner and Yiannis Gabriel, professors at the University of Bath School of Management, after discussion with individuals from professional bodies and trade unions, including the University and College Union, the Association of University Administrators and Universities UK.

THE will publish further analysis of the results during 2016, and the Times Higher Education University Workplace Survey 2017 will be rolled out later this year.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Whistle while you work?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login