Student activism during the dictatorship of 1964-85 is a far from obscure topic in Brazil. Many of today’s politicians began their careers as student activists in that era and, as Victoria Langland notes, Brazilians remain captivated by stories about the young men and women who rallied against a repressive military government.

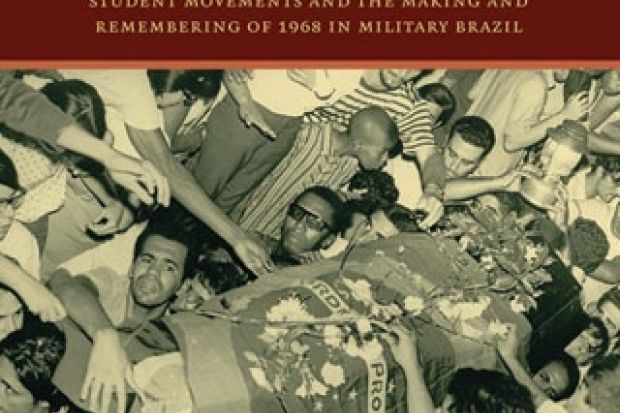

I am a Brazilianista cultural historian, and iconic images and the melodies of protest songs sprang immediately to mind when I first read this book’s title, which refers to Geraldo Vandré’s 1968 song Pra não dizer que não falei das flores (also known as Caminhando), popularised in protests after student Edson Luís was killed by police. The story of these student movements has been retold frequently in popular media: Globo’s 1992 television mini-series Anos Rebeldes, for example, interspersed historical photographs, songs, news footage and headlines with insipid soap-opera romance, commodifying the collective memory of the military dictatorship and student protests via what literary and cultural studies scholar Rebecca Atencio has called “memory merchandizing”. I dug into Speaking of Flowers eager to find a subversive critique of the mass media’s packaged historical narrative.

Langland’s accomplishment lies in providing the backstory of the student movements, tracing their changing relationship with the Brazilian state throughout the 20th century and contextualising them in the country’s political history. The National Union of Students (UNE) that emerged in the 1930s was elitist and male-dominated, a reflection of the general university student population in that era. But by 1960, the UNE had adopted a more radical stance in reaction to both local struggles and international Cold War politics, and this book’s central chapter on 1968 emphasises the tensions between local and international concerns. While Brazil’s student movements were rooted in protests against the military regime’s growing repression, global student movements influenced both their strategies and the public’s perception of their activities. Langland recounts how military officials used global 1968 movements to depict the rebellious actions of Brazilian students as a “foreign” aberration. This framework further unfolded in the 1970s as competing collective memories of the events of 1968 shaped not only how students saw their political role in attempts to dismantle the dictatorship, but also the military’s use of increasingly violent measures to repress “non‑Brazilian” protests.

Although Langland weaves the historical narrative in Speaking of Flowers from diverse sources that include oral history, periodicals and police records, they come mostly from Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. This is most problematic when she considers other states, because her accounts of student movements in Pernambuco and Brasília lack the local contextualisation that is so richly detailed in her analysis of the same period in Rio. This weakness reflects the challenges of covering a topic as large as this, since the student movements differed from place to place, changed over time, divided and had an ever-changing leadership and base.

The book’s gendered analysis is fascinating, as Langland illustrates how the student movements defined themselves and were perceived as male-dominated and masculine. In addition to considering their male leadership, she analyses the language students used to reinforce rigid gender categories and naturalise different roles for male and female students. While she addresses the (largely middle- to upper-class) socio-economic backgrounds of the activists, I would have liked her to consider the racialisation of the movements. Indeed, more attention to the absence of racial discourse would help us to better understand the history of racial exclusions from Brazil’s student movements, present-day debates over racial quotas in the country’s university system, and the racism that is both experienced and perpetuated by students.

Speaking of Flowers: Student Movements and the Making and Remembering of 1968 in Military Brazil

By Victoria Langland

Duke University Press, 352pp, £67.00 and £16.99

ISBN 9780822352983 and 53126

Published 11 July 2013

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login