Source: Miles Cole

I am by no means the first to observe that the current model of academic publishing is broken. It effectively requires universities to hand over largely publicly funded research to a handful of corporate oligopolies, which then copyright it and sell it back to universities at a very high price. This simply does not make sense.

The UK government’s decision to make all research funded by the British taxpayer universally accessible must be regarded as a significant victory for the open-access movement. The problem is that the open-access mandates with which funders have responded will do little to rein in corporate publishers’ infamously high profit margins.

The Finch Group’s remit to secure publishers’ consent for its recommendations led it to express a preference for the “gold” option, in which journal versions of articles are made open access - often in exchange for fees. This preference has also been adopted by Research Councils UK’s open-access policy, which came into effect on 1 April, leading it to reserve millions of pounds to pay the associated article fees.

We would do much better spending the money to support a variety of open- access initiatives that work in the interests of academics, universities, the government and the public, not the publishers.

One idea would be for the Russell Group and the 1994 Group of research- intensive universities to get together with Jisc and other members of the UK Open Access Implementation Group to set up a publishing platform controlled and run by academics. This could be modelled on Brazil’s Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO): a publicly funded, university controlled open-access platform that has operated since 1998 and currently hosts more than 900 open-access journals in a variety of disciplines run by scholars and learned societies.

These journals operate like any other, but SciELO’s provision of a free platform for reviewing and publishing papers means that production can be done without the help of traditional publishers. Quality is ensured by requiring all new journals to go through a simple yet rigorous application process, and the platform has recently been opened up to book publishers, too.

Let’s not forget that many UK academics and learned societies already self-publish their knowledge. I personally have co-founded and co-edited various open-access academic publishing ventures since 2000, most notably the journals Ephemera and Interface, as well as the book publisher MayflyBooks. There are many other examples in existence, such as the journals Surveillance and Society and Acme, and the publishers Open Humanities Press and re.press.

While setting up and running an independent open-access journal is, admittedly, not an easy task, the hurdles are not insurmountable given that academics already do most of the work required to put together journals, such as editing, peer reviewing and often even production. And learned societies have produced journals for decades, often for a much lower subscription price than corporate publishers.

But a UK version of SciELO would make things significantly easier, offering free technical and quality support while also providing a powerful indexing tool that would ensure accessibility and compatibility of content. It would counter the modern trend for increasing consolidation among academic publishers by encouraging hundreds of groups of scholars and learned societies to set up their own journals.

I can already hear colleagues objecting that academics want (and need) to publish in journals with established international prestige - all of which are in the hands of corporate elites that will protect their profits by any means necessary. But this argument ignores the fact that these elites are completely reliant on our continuous support: not only on academics’ willingness to submit their manuscripts and to edit and review those of others, but also on university libraries’ readiness to pay for access to the journals produced.

If we were to refuse that labour, resign from the editorial boards of corporate-run journals and set up open-access alternatives, publishers’ profits would quickly nosedive. And if we - particularly those of us with established careers and secure jobs - became more aware of the realities of the publishing industry and made a point of favouring the new journals, their prestige would soon rival that of the established market leaders.

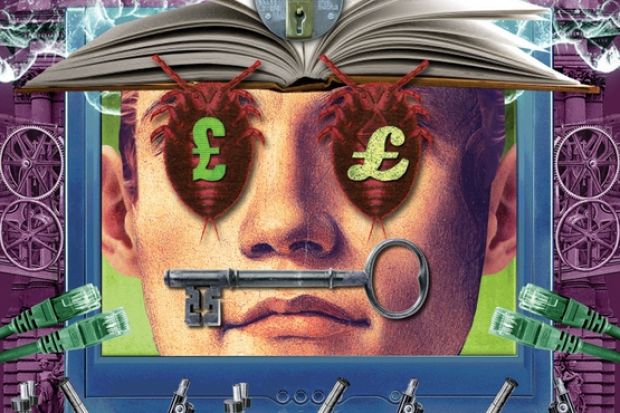

Such a concerted effort by all players could result in the UK becoming a beacon of open-access publishing. By cutting out the parasitic publishing middle men, the academy could reclaim control of its knowledge, funding and labour.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login