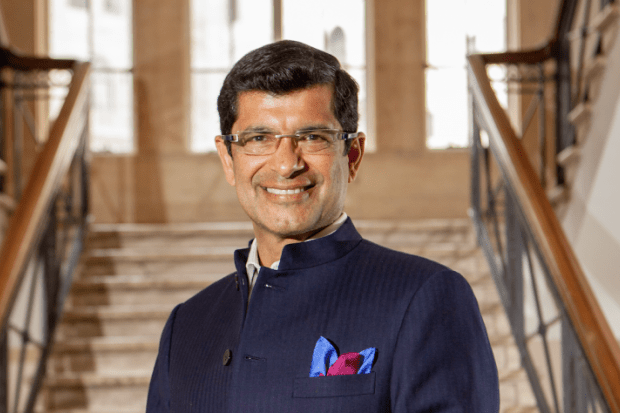

Universities are not toxic and people should stop using the term “snowflake”. Shitij Kapur, president and principal of King’s College London, has strong views on student mental health. With 35 years’ experience in psychiatry and neuroscience, he is in a position to know.

In the latest in our Talking Leadership series, Kapur sits down with Times Higher Education to talk about shaking up student support, changing the game for refugees, and how UK and Australian policy compare.

Student mental health surveys frequently find that about 30 to 40 per cent of students have mental health challenges. But this leads to misperceptions, Kapur says. One is that these students are ill. But such surveys “do not pick up what a psychiatrist would classify as mental illness,” he says. “They have challenges with anxiety and are often on the depressive spectrum, but they do not have a mental illness.”

THE Campus resource: Conversations around stress must move beyond ‘I’m fine, how are you?’

The second misperception is that the rate of mental health challenges is higher among students than in the average population. Studies have shown this is not the case, Kapur says.

“Universities are not in any way toxic places. This matter just gets more attention in universities.”

At the other end of the spectrum of views about student mental health is the stereotype that students are “snowflakes” – overly emotional and easily offended. Kapur dislikes this term, which he describes as pejorative and stigmatising.

“I think it’s very inappropriate,” he says. “People in their 50s and 60s will say, ‘Wow, I also went to university, you know, it was tough, but I never complained,’” he says. But “this generation is facing issues and challenges that those of us who are now in our 40s, 50s, and 60s did not, even before Covid. [Today's students are] the post-financial crisis generation. What the financial crisis did was change the possibilities of your future.”

He admits that younger people today are “perhaps a bit more anxious about the future”, but believes this is because they are more worried about society than previous generations. “I find that their circumstances are different and perhaps even more difficult and that they are more sensitive to the realities of the environment and equality.”

A toolkit for mental health

Since returning to King’s as leader in June 2021 – he was previously dean of the Institute of Psychiatry, among other roles, before a four-year stint in Australia – Kapur has made improving student mental health one of his priorities. The university is “reassessing at the very basic level how our bread-and-butter business of providing education can remain as challenging, as demanding, if you may, without becoming inadvertently stressful”, he says.

King’s has helped develop a new “Education for Mental Health” toolkit, in partnership with the University of Derby, Aston University, Advance HE and Student Minds, with funding from the Office for Students.

Counselling services are not enough, Kapur believes. Supporting student mental health must be embedded throughout the university, starting with the curriculum. Ensuring students are prepared with basic skills, such as note-taking, from day one helps with this, he says.

This work may also require rethinking timed assessment. Expecting someone to prove that they understand a topic, such as geopolitics, in three hours doesn’t make sense, according to Kapur.

“What Covid has taught us is that that time pressure isn’t necessarily the best way to assess for some things,” he says.

The next layer of Kapur's plan involves the 30 to 40 per cent of students who find university more difficult than others. “The issue is, can you actually reach out to this population and equip them in a preventative way before their challenges become manifest?”

King’s has experimented with a couple of approaches, using research by its own academics that looked at what well-being means for students. “What they learned is that around the very core nexus of having appropriate mental health – in other words, that you’re not anxious, and you’re not depressed – well-being is a positive attribute much greater than that. And it has three or four other aspects that core mental health does not capture.”

These aspects beyond the absence of anxiety and depression include social connectedness and the ability to cope with stress. The third draws on positive psychology, and is about fostering positive emotions and a sense of meaningfulness and accomplishment in what you’re doing.

King’s initially introduced two credit-bearing modules teaching students mental health resilience, drawing on positive psychology, one for psychology students and the other for nurses; these are now offered to all students.

“There are some lectures. But more importantly, there is some behavioural homework. So you have to take those things away. And then you have to apply them in your life. And then the third thing is you need a reflective discussion in a feedback loop,” he says.

If positive psychology teaches the importance of belonging, what does Kapur think about the impact of hybrid working? Will less face time mean students feel less of a sense of community? He pauses. “It is a real challenge…you cannot have a very good sense of well-being, unless you have a reasonably settled sense of identity and belonging.”

“Genuinely, we don’t know the answer to that,” he continues. “But there is no mistaking that there is no free ride, that if you think that you can have less human interaction and somehow the sense of identity and belonging will be the same, no.”

Attachment is rarely abstract, Kapur says; it is linked to places with rituals and symbols: “For example, Christians who go to church feel a sense of community. It’s not just a belief in a certain theology; it is everything else that happens around it. And in many ways, universities are similar.”

At King’s, from next year, students will be guaranteed as much face-to-face time with their professors as they had pre-Covid, although the nature of it may change. Lectures may move online, while seminars take place in person, he says.

Hidden curriculum

One element of the new mental health toolkit urges lecturers to consider the “hidden curricula” – aspects of the curriculum that implicitly communicate certain values, which can impact students.

Having been born in Montreal and brought up in India, and having spent many years in the UK and Australia, what does Kapur think about this?

“Ours is inherently a Western system of knowledge, which has been, because of its success, a very dominant system of knowledge, and which has been adopted by a very large number of countries, because they find it effective and successful,” he says. “I think over the last two or three decades, what we are developing is an insight into that reality of it.”

We are beginning to realise that “most of the world of knowledge is informed in some sense by position and by perspective”, he adds. “A belief in the universal truth of everything is being shaken up a little bit. So, therefore, across all the universities, there is a very legitimate questioning of the source of knowledge, of the biases that are inherent and, in some cases, a very proactive effort to balance that.”

From a mental health perspective, this questioning means that if “you do not come from the dominant stream, whatever the dominant stream is, in some sense, the curriculum feels a little bit alien to you...[which means] that you do not engage as naturally with it.”

Early career researchers

Another group in the higher education sector that is known to be suffering is early career researchers. With relentless pressure to publish and seemingly endless rounds of temporary contracts, how does Kapur believe their mental health can be improved?

He sympathises and points out that they are in a more difficult position now than when he was early in his career, with many more postdocs fighting over the same number of positions.

“What has happened, however, is that a number of other avenues and positions have been opened. There are more positions in government, there are more positions in industry, there are more positions with the NGOs,” he says.

Universities must get better at preparing postdocs for these roles, he adds, which includes changing attitudes.

“The general culture is such that the feeling is that if you can’t get one of the tenured positions, that’s almost been a failure,” he says. “Early career researchers find themselves in this bind, that they are brought up in a culture which only really values one outcome. But the prospect of achieving that is limited.”

Refugees

Another innovative move by King’s is its support of Ukrainian refugees; it recently became the first university to act as a community sponsor for a refugee family. Kapur explains that it had gained approval for the status in December 2021 to support a Syrian refugee student and her family in coming to the UK, and scaled up the programme when Russia attacked Ukraine.

Working with the charity Citizens UK, it has offered to welcome 50 refugee families who will be hosted by King’s staff. Other King’s volunteers will support them with applying for education, accessing healthcare, learning English and more. They are also working nationally to help other universities navigate the administration around becoming a community sponsor.

UK vs Australia

Before returning to King’s, Kapur spent more than four years at the University of Melbourne, where he was dean and assistant vice-chancellor (health) for the faculty of medicine, dentistry and health sciences and interim deputy vice-chancellor (international). So how does higher education in the two countries compare?

They’re similar, Kapur says. Both nations opened up their systems to marketisation, but then decided they had gone too far. Both are also questioning the value of the graduate degree and comparing it to other post-secondary options.

On current UK policy, Kapur believes that if the potential minimum entry requirements mooted by the government are simply to limit the numbers going to university, and not part of a broader programme to strengthen other post-secondary options, then the policy is “retrogressive”.

“The Britain of 2050: if we think that we will get away with only 50 per cent of the people having post-secondary education, we will not be the first-rate nation we want to be, we will not be the science superpower we want to be,” he says.

Quick facts

Born: Montreal, 1966, but grew up in Delhi

Academic qualifications: Bachelor’s in medicine from the All India Institute of Medical Sciences; PhD in neuroscience from the University of Toronto

Lives with: His wife

Academic hero: Philip Seeman, professor of pharmacology

This is part of our “Talking leadership” series of 50 interviews over 50 weeks with the people running the world’s top universities about how they solve common strategic issues and implement change. Follow the series here.

后记

Print headline: King’s leader tackles mental health myths