Dwight McBride is a name-dropper. Not of celebrities but of academics he respects; his speech is peppered with mini shout-outs, frequently to people of colour.

As a black, gay man in the higher echelons of US tertiary education, the president of The New School, an elite private university in New York, understands the obstacles minority academics must scale.

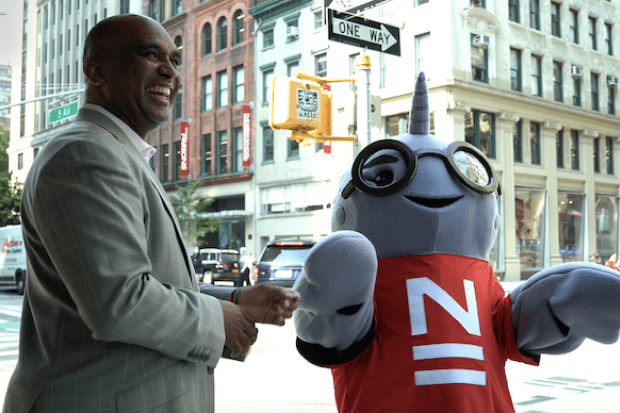

“Every time I see a successful black scholar, Latinx scholar, Asian American scholar and so on thriving at high levels of distinction, I feel like I’m in the presence of a unicorn,” he says. “I understand how absolutely challenging it is in every conceivable way to arrive in these spaces at that level.”

The race and literary scholar, who has a deep love for James Baldwin, has charged through life achieving firsts: the first in his family to go to university, now the first person of colour to lead The New School. But his ebullient nature belies a certain exhaustion.

Being the only scholar of colour, or one of a few, brings a whole heap of extra work, McBride explains. “Literally from every quarter of the university, students seek you out because you’re someone who looks like them; they feel they can talk to you.”

This extra mentorship – “I’m not going to say no to it, I don’t send them away” – along with educating others on issues of race, can be “crippling”, he says, “and can really pose limitations on one’s ability to advance in a career”.

Diversity

Since becoming president in April 2020, McBride has been committed to tackling this issue at The New School. With the help of a $5 million (£3.7 million) grant from the Mellon Foundation, the university is recruiting more fellows from diverse backgrounds: PhD students and postdoctoral fellows, as well as more senior academics.

The New School has also co-founded the Academic Leadership Institute with the University of Michigan to help diversify leadership positions in higher education.

McBride is part of a network of black presidents of US universities, and through discussions with these peers, he has come to realise that boards should be doing more to prepare institutions when they appoint the first of some type of person to a senior position, whether that’s a person of colour, a woman or someone from another marginalised group.

“You don’t walk in with the same kind of credibility as a white guy doing the same job walks into the room,” he says. “If one doesn’t learn a way of negotiating it, it can ultimately make for a challenging tenure in many of these roles.

“There is a way in which that also has a tax that the institution is rarely prepared for or has thought about.”

To mitigate this, it is imperative that the issue is addressed, he says. “The most important thing you can do is to not ignore it.” There need to be “real and candid and honest conversations about topics that Americans are really awkward talking about: race, gender, sexual orientation.”

As well as looking inwards, universities have a duty to lead on issues of equality, inclusion and social justice out in the world, McBride believes. Not because they are paragons of democratic perfection but because they have been complicit in discrimination.

“From [their] very inception, our fundamental institutions have participated in and been informed by and undergirded by white supremacy. So it is no surprise for those of us who are students of history that there continues to be work to do in terms of the institutions that make up our society. The university is one of those institutions.”

The New School could lay claim to being one of the more progressive universities in the US, however. Founded in 1919 by scholars committed to an institution where faculty and students would be free to honestly debate the problems facing society, in the 1930s it was a refuge for academics fleeing totalitarian regimes. It proclaims to have had the first university-level course in women’s history in the US and today even its university mascot is gender neutral.

Does McBride believe that some of the universities with less auspicious foundation stories, such as those built on the backs of slavery, have more of a duty to stand up for social justice?

“I don’t know if they’ve got more or less; I think they certainly have the same obligation,” he says. “I think the difference is that some of the work that we have to do, given our unique histories, may look different.”

The institution he previously worked at, Emory University, is now grappling with the question of how to address memorialisations and professorships named after those no longer deemed worthy of admiration. “That’s a part of the work as an institution born in the South in the 19th century. That work is going to look different at Emory than it will at The New School, but I think the work is important and necessary in both contexts,” he says. The New School does, he points out, sit on indigenous land.

McBride’s self-belief and activist inclinations are a product of a clash between his early childhood and school years.

Born in South Carolina, he explains that “my world growing up until I started school was a very black world. I saw me reflected in those early years. I saw black teachers and preachers and lawyers and they were the heroes of our community.”

He spent much time in church where “my loquaciousness was rewarded. People thought that was amazing. And I felt a lot of sense of my own value,” he adds.

Then when he went to a racially integrated school, he first encountered spaces where “my value was not reflected back at me”.

“In retrospect, it was an enormous education. Because I know what it feels like to be in a community where I feel included. But I also know what it feels like to be in a community where I feel like I’m constantly having to prove myself and my worth and my value. And so it was, in some ways, that dichotomy that was really informative,” he says.

Democracy

Recent events in the US have rattled McBride, the Trump presidency and the 6 January 2021 incursion of the Capitol, in particular.

“I am even more stunned and horrified and afraid, because so many people seem so willing to be dismissive of it, and to discount it as something that needs to be taken seriously,” he says of the latter.

“The peaceful transfer of power is such a bedrock of any democracy” that he could not have conceived of it being challenged. “It may have been my own naivety,” he says.

McBride’s tactic in the face of this shock is to “begin again”, as suggested by his hero James Baldwin, the black writer and activist born in New York in 1924. Here, he references a book, Begin Again: James Baldwin’s America and Its Urgent Lessons for Today, by Eddie Glaude, chair of the department of African American studies at Princeton University (“a great colleague and friend and someone I have deep respect for”).

“Baldwin calls us – in moments like this, where you start to lose hope, where you start to feel less optimistic about the future – to begin again, to go back to the fundamentals,” McBride says. “And for me this last five years has been a call to go back to ask the questions about what is our work, what is my work, as a scholar? What is my work as an academic leader, as a university president?”

The fragility of democracy is something universities can and should be doing something about, McBride believes. At The New School, this involves working with the Institute for Citizens and Scholars, a non-profit that supports leadership development. “Working with them, we’ve been asking questions about what role we should be playing in civic and civil education,” McBride explains.

Some have argued that universities lack right-wing scholars, leaving them open to accusations of liberal elitism. For example, in his recent book What Universities Owe Democracy, Johns Hopkins University president Ron Daniels writes that university leaders should be asking “why so many disciplines suffer from a dearth of conservative faculty in the first place and what the consequences of that imbalance are”. Does McBride agree?

“I’m not sure that the problem is the lack of a right-wing perspective in universities,” he says. “I’m not sure that’s the problem.”

“I think there’s a wide variety of opinion at The New School among our faculty, and people who certainly have vigorous debate with each other. The thing is that, you know, progressives have been painted with a very broad and unflattering brush in this country. And that’s just not my experience.”

Quick facts

Born: South Carolina, 1967

Academic qualifications: BA in English and African American studies from Princeton University; MA and PhD in English from the University of California, Los Angeles

Lives with: Alone

Academic heroes: Toni Morrison and Ruth Simmons, president of Prairie View A&M University

rosa.ellis@timeshighereducation.com

This is part of our “Talking leadership” series of 50 interviews over 50 weeks with the people running the world’s top universities about how they solve common strategic issues and implement change. Follow the series here.

后记

Print headline: Scholar says educating on race can be ‘crippling’