In 1904, my Jewish paternal grandfather deserted from the army of Tsar Nicholas II and fled to England. I once asked him why. He replied: “Kishinev”.

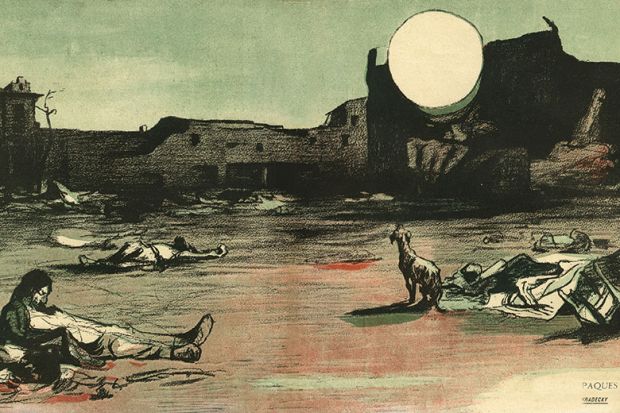

Kishinev is now the capital of the Moldovan Republic. At the beginning of the 20th century it lay within the Bessarabia governance of the Russian Empire. On 19 and 20 April 1903, its Jewish population was subject to a series of brutal, sustained and – as it turned out – organised attacks. Forty-five Jews were killed. Hundreds were injured. There was widespread raping of Jewish women and girls. There was wholesale destruction of Jewish property and systematic looting of Jewish-owned shops.

Thanks to the efforts of the American newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst – and of the special correspondent whom Hearst had dispatched to the town (the Irish nationalist Michael Davitt) – authoritative eyewitness accounts of the pogrom were soon read worldwide. The accounts caused outrage in the West. Some months later, a young Russian-Jewish scholar, H. N. Bialik, wrote in Hebrew a poem that reflected on the pogrom. Like Davitt, Bialik travelled to Kishinev and interviewed many eyewitnesses. Yet the poem – In the City of Slaughter – amounted to an angry denunciation of the Jews of Kishinev, whom he accused of cowardice. To the young Zionist movement, then struggling to legitimate itself in the Jewish world, the popularity of Bialik’s poem proved a turning point.

These are two of the stories Steven Zipperstein has set out to tell. There are others. Mining an awe-inspiring array of sources, his book offers an hour-by-hour account of two days in the life of a city in which it had been said that Jew and non-Jew had been living contentedly side by side. This turned out to have been a myth. Beneath the surface there was a raw hostility – part religious, part economic – towards everything Jewish in the city.

Jewish households were ransacked by non-Jewish neighbours living in the same street. A Jewish woman was raped by a man she had known since his childhood. Jewish residents did try to defend themselves, but they were overwhelmed. It is equally untrue that the Tsarist authorities stood idly by. Law and order was, however, improperly deployed and of insufficient strength.

The evil genius behind the pogrom was Pavel Krushevan. A native Moldovan, he craved recognition and had used his news-sheet (Bessarabets) to launch weekly tirades against the Jews.

Zipperstein paints a grim picture of Krushevan as a psychopathic ultra-nationalist who was also the author of the first edition of the notorious The Protocols of Elders of Zion.

Zipperstein’s analysis of Kishinev – and of its impact on the Jewish condition worldwide – is probably not the last word on the subject. But for the present it must remain the most authoritative account we have.

Geoffrey Alderman is Michael Gross professor of politics and contemporary history at the University of Buckingham.

Pogrom: Kishinev and the Tilt of History

By Steven J. Zipperstein

Liveright, 288pp, £22.00

ISBN 9781631492693

Published 27 April 2018

后记

Print headline: An account of raw hostility