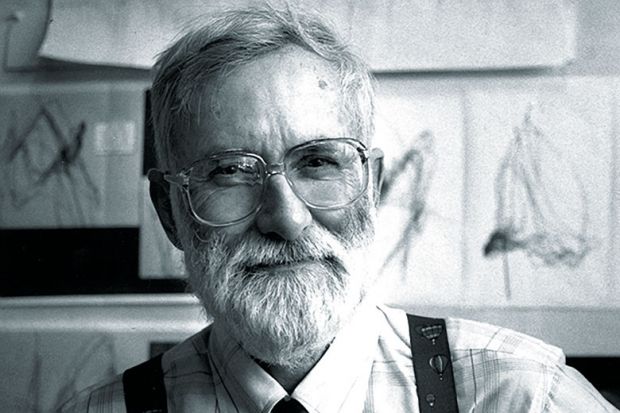

Walter Jackson Freeman III was born in Washington DC on 30 January 1927, a descendant of the Unites States’ first brain surgeon.

Although he studied physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, English and philosophy at the University of Chicago and electronics while serving in the US Naval Reserve, he never received a bachelor’s degree but went straight on to Yale Medical School, where he graduated cum laude in 1954.

He then joined the University of California, carrying out postdoctoral research in neuropsychiatry at the University of California, Los Angeles before, in 1959, moving to the University of California, Berkeley for the rest of his career. He was chair of the department of anatomy and physiology from 1967 to 1972 and eventually retired as professor emeritus of molecular and cell biology.

A pioneer in the field of computational neuroscience, Professor Freeman initially worked on the sense of smell in cats and rabbits, using data from electroencephalograms or electrodes inserted into the brain to produce mathematical models of how perception works. He would later develop his findings in nearly 500 research papers and books such as Mass Action in the Nervous System (1975), which explored memory and motor as well as olfactory systems.

While much of Professor Freeman’s statistical work on brain dynamics and neural networks was inevitably highly technical, he was also committed to bringing his ideas to a more popular audience in publications such as Societies of Brains: A Study in the Neuroscience of Love and Hate (1995) and How Brains Make Up Their Minds (2001).

Furthermore, he rejected any simple “circuit board” model of how the neurons in the brain work together and always stressed the sheer scale of the self-organising networks required for activities such as perception. He was also happy to venture into questions of mind, consciousness and personality that had hitherto been largely the domain of philosophers.

“The brain reaches out into the environment and sees something which is then interpreted according to its own past experience,” Professor Freeman explained in a 1991 interview. “First you look, then you see. The process of recognition begins from within.” He also expressed sympathy for the unified model of brain, body and mind (or soul) developed by the 13th-century philosopher and theologian St Thomas Aquinas.

Professor Freeman continued to work every day, and even to walk to campus, until very recently. He died of pulmonary fibrosis on 24 April and is survived by seven children, five stepchildren and 18 grandchildren.