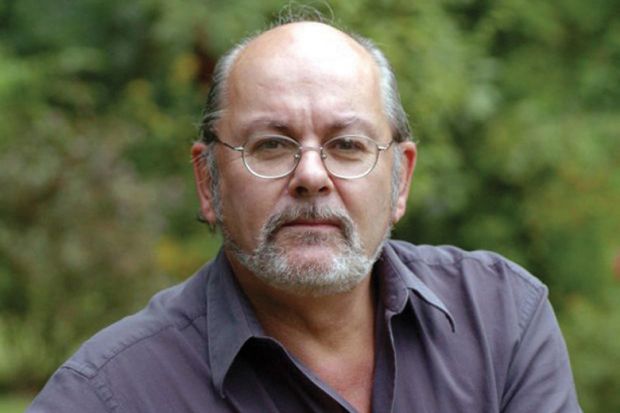

John Benyon was born in Southampton on 10 March 1951 and studied as a mature student at the University of Warwick before joining the University of Leicester as a lecturer in public administration in 1981, working in both adult education and the department of politics. He was promoted to senior lecturer in 1987 and professor of political studies in 1993.

Although his research initially focused on planning and local government, Professor Benyon soon turned his attention to the riots that erupted in a number of British cities in the early 1980s along with official responses to them such as Lord Scarman’s report on the Brixton disorder of April 1981. This led to a major book, Scarman and After: Essays Reflecting on Lord Scarman’s Report, the Riots and Their Aftermath (1984), followed by The Police: Powers, Procedures and Proprieties (with Colin Bourn, 1986) and The Roots of Urban Unrest (with John Solomos, 1987).

As a result of such work and his links with Lord Scarman, Professor Benyon established the Centre for the Study of Public Order at Leicester in 1987. This would become the Scarman Centre in 1997 and later the department of criminology. Along with producing major studies such as a jointly authored report on African Caribbean People in Leicestershire (1996), the centre was a pioneer in distance learning and created a number of successful programmes, some still running today.

In 1999, Professor Benyon moved on to run Leicester’s new Institute of Lifelong Learning, before shifting to a position as director of research from 2008 until retirement in 2015. In the same year, he received a Lifetime Contribution award from the Political Studies Association, for which he had served as treasurer for more than 20 years.

Ken Edwards, vice-chancellor of Leicester from 1987 to 1999, recalls Professor Benyon as a scholar and administrator whose “enthusiasm and energy were truly impressive, even if his activities occasionally created waves which caused turbulence elsewhere and required a discreet intervention by the vice-chancellor. He was very productive and stimulated others with his enthusiasm. He was open and direct in ways which I appreciated. He put forward his ideas and points of view, which were often challenging, but with honesty; he and I often had vigorous conversations, but without edge, and usually ended in agreement.”

Professor Benyon died of mesothelioma on 19 May and is survived by his wife Colleen and his daughter Danni.