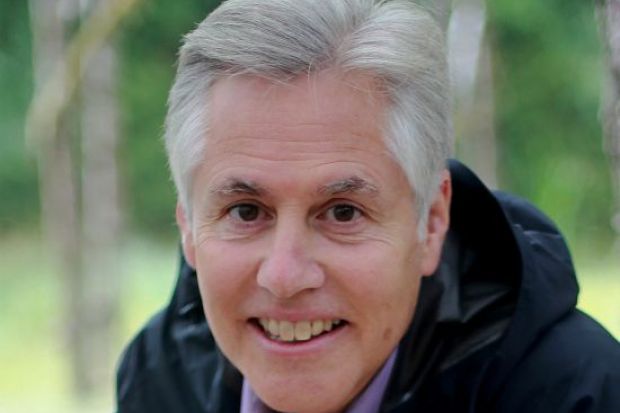

John Borrows is Canada research chair in indigenous law at the University of Victoria. He’s an Anishinaabe, of the Chippewa of the Nawash First Nation in Ontario and the 2017 winner of the Killam Prize in Social Sciences. He’s also a fellow of the Academy of Arts, Humanities and Sciences of Canada, and last month received an appointment to the Order of Canada, which is one of the nation’s highest civilian honours.

Where and when were you born?

Toronto, Ontario, in 1963.

How has this shaped who you are?

I grew up on a farm about an hour north of the city. It was a quiet place. It has four strong seasons full of wonder and change: planting, growth, harvest and rest. I was immersed in this beauty. I am Anishinaabe, and my mother taught me how our indigenous ancestors watched the natural world. Everything had something to teach us: rocks, water, trees, birds, fish, animals and insects. They all had their own personalities and our mother would tell us their stories as she learned them.

That helps explain your interest in indigenous affairs, but why law?

Partly because my mother was teaching me indigenous laws. Also, my great-great-grandfather signed a treaty covering 1.5 million acres of land in Ontario, my great-grandfather was a chief for 50 years, and my grandfather was a Hollywood Indian before going back to the reserves.

A Hollywood Indian?

His name was Josh Jones, and he moved down there in the 1930s for the cowboy and Indian shows. He was part of quite a network of people in that era, including [indigenous athlete] Jim Thorpe. The Native Americans had a union, and would work to advance one another’s participation and employment, including in movies.

He’d play the role of an ‘Indian’ in movies?

Yeah, the bad guy.

And dress in stereotypical mocking Western versions of Native Americans?

Exactly. He grew up with a lot of oppression on the reserve, so he went off to make his way in the world. It was often a kind of self-deprecating thing – he went to Hollywood and ended up falling off horses. He ended up undermining the very thing he was trying to advance, just because there were limited opportunities for the portrayal of indigenous peoples at that time.

What’s your take on that?

At the time it was making money, which was important during the Depression. He kind of made fun of himself in the 1950s and 1960s because of the negative stereotypes, and now we take it as a cautionary lesson.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

I started school at age 21, married at 22 and had children at 23 and 25. So my school experience was very much about raising a family.

What brings you comfort?

People who exude peace, and being with others who find this in simple food, music and low-key discussions.

What saddens you?

Clear-cut forests.

Why that?

There’s an aesthetic that saddens me, having grown up in the country and seen the vibrancy of life. It’s like cutting down a library, because your sources for looking at what you might do have been homogenised or destroyed. I finally understood that my mother had been teaching me Anishinaabe law when Basil Johnston, an elder from our reserve, told me that “the Earth was our textbook and the land was our legal archive”. He said when humans understand how to interpret the world by analogising and distinguishing our actions in relation to the natural environment, then we are on the path to harmony with it.

Why should an average citizen care about your work?

If we can learn to see law as something we do, in partnership with the Earth, rather than something that is done to us and the Earth, then law becomes an activity for everyone’s participation, not just legislatures, courts, lawyers, judges and policy officers.

What’s the big difference between Canadian law and indigenous law?

Indigenous law references the land as a source of authority for making decisions. So the cases would be the stories that are attached to the water and rocks and plants and birds. You reason from those observations and cases and language and stories about how humans should react in that same place.

But a rock doesn’t tell you what it believes.

Exactly. You have to counsel together and discuss what that rock is meaning in that instance. There’s lots of meaning for rocks; there’s lots of stories about the rocks, scientific observations through the ages about what happens when you move that rock or have this thing happening on the landscape.

Tell us about someone you’ve always admired.

My sister. She has cerebral palsy and is dyslexic and struggled in school. Yet she worked hard, learned how to deal with these challenges, and received her PhD in counselling. She works on our reserve and helps people understand their own great power, and brings resources and ideas to their attention. She is in the trenches working on the healing of our people in a day-to-day way.

What are the best and worst things about your job?

I love learning with and from students. I don’t like how we evaluate them. I think the standards we use are too narrow.

In what way?

I administer law school exams and we pose hypothetical fact situations. That’s all well and good, but students also need to be able to interview clients and make presentations before legislative committees, and research complex problems. Also, we don’t think about honesty, kindness, morality, ethics. There is something called legal ethics, and we talk about it, but we don’t usually evaluate it.

What keeps you awake at night?

Violence against indigenous women and children is widespread in North America. It troubles me more than almost anything I know. I try to teach and write about this but I don’t think I have found the best way to combat this yet.

paul.basken@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Tom Ward is moving to Newcastle University as pro vice-chancellor for education. Professor Ward, formerly deputy vice-chancellor for student education at the University of Leeds, will move to the north-east in May, replacing Suzanne Cholerton following her retirement. He is a professor of mathematics who has also overseen education strategy at Durham University and the University of East Anglia. Chris Day, Newcastle’s vice-chancellor, said Professor Ward’s “experience and strong track record of working with the student body” would be vital in overcoming the challenges presented by Covid-19.

Ross Renton will be the first principal of Anglia Ruskin University’s new campus, ARU Peterborough. He will join the £30 million institution – construction of which began in December – later this month, ahead of its opening in September 2022. Professor Renton is currently senior pro vice-chancellor for students at the University of Worcester, and before that was dean of students at the University of Hertfordshire. Professor Renton said that he was “looking forward to working with our many innovative partners to take forward this pioneering approach to building a vibrant, creative and inclusive university for Peterborough and the wider region”.

Anglia Ruskin has also appointed Barbara Pierscionek as deputy dean for research and innovation in its Faculty of Health, Education, Medicine and Social Care. She is currently associate dean (research and enterprise) in Staffordshire University’s School of Life Sciences and Education.

Janine Deakin is the new executive dean of the Faculty of Science and Technology at the University of Canberra. She has previously served as deputy dean.

Tracy Bhamra is joining Royal Holloway, University of London as senior vice-principal for student and staff experience. She is currently pro vice-chancellor for enterprise at Loughborough University.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology has named Katie Hammer as its next vice-president for finance. She is currently deputy chief financial officer for the City of Detroit.