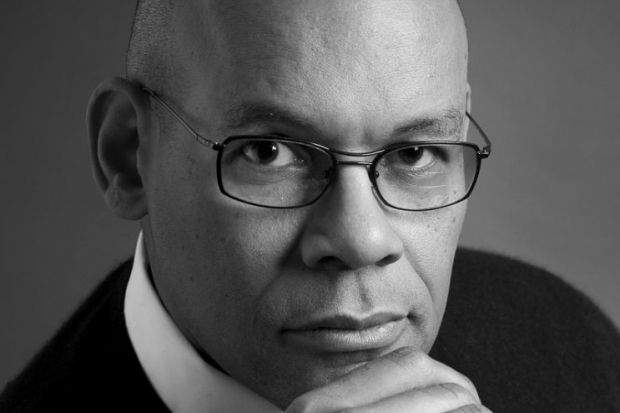

Jeffrey C. Stewart is professor of black studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. His book, The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke, about the Howard University professor who became father of the Harlem Renaissance, won this year’s Pulitzer Prize in Biography.

Where and when were you born?

I was born in Chicago, Illinois in 1950.

How has this shaped who you are?

Chicagoans have a great deal of pride, self-esteem and assertiveness. I feel I absorbed those qualities not just from my family but from the people I knew growing up.

What kind of undergraduate were you?

I was that type of undergraduate who wanted to expand and grow intellectually in college, rather than simply hang out and party, although I enjoyed my fair share of the latter as well. I majored in philosophy at the University of California, Los Angeles, but then transferred to UC Santa Cruz after Angela Davis, whom I was planning on taking a class from, fled from state persecution and went underground. I joined the Black Student Union in my freshman year and that too was a kind of school, in which I learned the dialectics of political philosophy in meetings with other black students just as much as I did in my philosophy classes.

Why did you choose to spend your career studying race and culture?

When I attended UCLA in the late 1960s, race and society were burning issues that almost every student had to grapple with. For me, that grappling was enjoyable, even as the issues and the persistence of problems of race remained deeply frustrating. Putting my undergraduate study of philosophy and my graduate work in American studies together, I wanted to produce philosophical critiques of American culture, to think of how we could rethink American culture to make it more inclusive, but also more stimulating and self-aware. I also noticed the lack of curriculum on race and African American culture in the American academy and that gave me a sense of mission, that I could help rectify the situation by writing and studying in this area [of] knowledge and cultural formation as it occurs at the intersection of race and culture.

Why were you drawn to writing about Alain Locke?

I was intrigued by a black man who was one of the first to be trained as a philosopher at Harvard, Oxford and Berlin and who found a way to engage race as an aesthetic platform, rather than a political one. It intrigued me that in an area dominated by political leaders such as Frederick Douglass, Booker T. Washington, and W.E.B. DuBois, Locke chose to advocate that African Americans could find liberation through art. He suggested something unique, at least in this arena of knowledge – that art offered a path to catharsis for black and white Americans to overcome the barriers of race that was not offered by other paths. Locke intrigued me because he suggested racial change was as much an internal, spiritual struggle and transformation for the nation as a material one. And what made him even more interesting was that in the 1980s and 1990s, the nation witnessed an upswing in black creative and cultural expression of the type that Locke had predicted in the 1920s. So I was captivated by someone who was so prescient and yet largely unknown.

How do you assess the progress that has been made on improving diversity and equality in America?

Actually, Alain Locke theorised about how progress occurs in race relations...he argued that race relations changed over time in reaction to economic and demographic forces, with the result that a kind of rhythm existed in racial progress. Periods of progress were often followed by periods of entrenchment. Relying on his theory, we can say that in the early part of the 21st century, there has been an enormous advance in diversity and equality largely led by exceptional African Americans, such as Barack Obama, and exceptional cultural production by such figures as Kehinde Wiley and Kara Walker in art, Toni Morrison and Colson Whitehead in literature, Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar in music and video, Barry Jenkins and Isaac Julien in film – a development that Locke predicted. But, at the same time, the plight of the masses of black people in America seems worse in the 21st than it was in the late 20th century, driven in part by the phenomenon some have called “anti-blackness” in the nation. Educational, health, political and social disparities along racial lines are large and growing, and there seems to be no national alarm about what is happening in largely segregated black communities. The challenge for America moving forward is to find some way to acknowledge and respect the humanity of the people who have created America’s most admired popular culture.

Have you had a eureka moment?

Yes, my eureka moment came during my sabbatical in 2016 when I was revising the entire manuscript of the biography. I discovered a pattern – that Locke reinvented himself largely in reaction to the men he loved. In other words, after years of hearing people tell me that I could write about Locke without referencing his sexuality or that his sexuality was just a feature to his life, but not critical to his thinking, I discovered that his thinking and loving were intertwined in a profound way. Men he loved helped him to grow intellectually. This insight helped me to make the importance of love in the lives of intellectuals the main takeaway from this biography.

What’s your biggest regret?

That I never actually got to meet Alain Locke. It would have helped a great deal to know the man I wrote about. I also regret that I didn’t continue the intense study of chess I began as a young man. If I had, maybe today I would be an international master!

When were you, or are you, happiest?

When I am hanging out with my children – they are my bliss.

ellie.bothwell@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Ian Campbell has been appointed vice-chancellor and chief executive of Liverpool John Moores University. Currently deputy vice-chancellor at the University of Hertfordshire, Professor Campbell will take up his new role in October. A professor of applied physiology, his primary research area over the past 30 years has focused on the physiology of individuals with a spinal cord injury during exercise. “This is clearly a committed and upbeat university that reflects the spirit and generosity of the city and I can’t wait to join and lead the university into its next chapter,” said Professor Campbell.

Susanna Scarparo has been announced as pro vice-chancellor (student life) at the University of Sydney. Starting in October, she takes over from Wai Fong Chua, who had been interim in the role since February. Dr Scarparo is currently associate dean (student experience) at the Australian National University. Pip Pattison, Sydney’s deputy vice-chancellor (education), said: “Dr Scarparo will continue the good work of Professor Chua, with her really impressive skills and experience, as well as her real passion for student welfare and learning.”

John Allan has been appointed new chair of Council at Imperial College London. A mathematical sciences graduate from the University of Edinburgh, with a 2006 CBE for services to freight transport, he will succeed Sir Philip Dilley in January 2020.

Maureen O’Rourke has been named associate provost for faculty affairs at Boston University. She will be responsible for the recruitment and appointment of faculty on the Charles River Campus.

Gideon Henderson has been appointed chief scientific adviser at the UK government’s Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. Currently a professor of earth sciences at the University of Oxford, he will take up his new role in October.