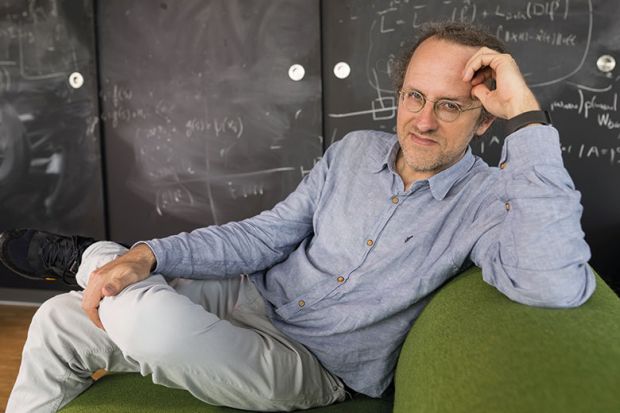

Bernhard Schölkopf is a director of the Max Planck Institute for Intelligent Systems – which is based in Stuttgart and Tübingen – and one of the world’s leading machine learning researchers. Last month, he received the Körber European Science Prize, a €1 million (£900,000) award, for developing mathematical methods that have helped “artificial intelligence reach its most recent heights”. He is also a founder of the European Laboratory for Learning and Intelligent Systems, which aims to keep Europe competitive in AI.

When and where were you born?

1968, in Stuttgart.

How has this shaped you?

I grew up in the countryside, half an hour to the south of Stuttgart in a small village. I ended up getting interested in things that nobody around me was interested in, like astronomy and physics, and I don’t really know where it came from because nobody in my family was into these things. I remember I had a children’s encyclopedia, and it had a few pages about astronomy – I was obsessed. I just loved watching stars and I bought a telescope early on, at maybe 12.

What kind of student were you?

I was quite broadly interested. I registered not just for physics and mathematics but also philosophy, and took courses in archaeology, anthropology and literature. But at the same time, I was a serious student – I took the hard-core mathematics stuff seriously. I wanted to be an academic – I think I knew that relatively early on. You have this feeling that if you ultimately want to understand the world at the very basic level, it has to happen at the level of theoretical physics.

Why did you go from physics to machine learning?

When you start physics, you naively think you will learn what keeps the world together. But when you get to quantum mechanics, you get thrown back into the role of the observer, and suddenly things don’t look so objective any more. So the act of observation, and the act of the human finding structure in the world, becomes a topic of research once again.

How would you describe your research?

What really interests me is how we – or how any intelligent systems, humans or machines – can find structure in the world. Why does the world look structured and regular rather than random? How do we find these regularities? How do you recognise patterns and objects?

We constantly read headlines about how artificial intelligence is going to change the world. What is hype and what is not?

We really made major progress on hard problems such as object recognition and machine translation. But if we’re honest, in all those problems we’re working in a setting where we have data that are representative of the task that we want to learn, and where the future looks the same as the past. Machines are not very good at transferring knowledge from one problem to a related but different problem; that’s something that humans are very good at. So there’s a danger that we are naively extrapolating from these impressive results. Everything that’s related to super-intelligence, I would say at this point, is hype.

During your career, you’ve worked at a number of private labs, including last year at Amazon, as well as public institutions. Do you get many offers from technology companies? And are they tempting?

All the companies are recruiting, and many [academics] get asked regularly, including myself. What I’m looking for is a stimulating environment where I can learn something and work with the best possible people. At any given point, there are amazingly attractive industrial research labs. At the same time, none of them has historically reached the stability of an academic environment. There’s a reason why in the end many of the most surprising developments come from academia – I think it may be related to tenure, which gives people complete freedom, stability and independence. It’s a model that seems to work.

You’ve worked in the UK, the US and Germany. How does the research culture differ from country to country?

When I moved to London, it was quite a revelation how the interaction with the professors worked there. One of my first professors sat there chatting to me with his feet on the table – it was something I had never seen from a German professor; things were more formal there. This guy in London talked to me like a scientist would to another scientist. My UK university experience was great, but in Germany, on the other hand, we have the Max Planck system. I think it works amazingly well as it’s very single-minded and driven only by science. It has the most pure mission – it’s all about improving our basic understanding of the world. In the US, apart from the universities, the private sector works very well – the kind of science that these companies are doing is quite impressive.

What one change would make your working day better?

I spend too much time on email. I would like to have longer uninterrupted stretches of time that I spend alone or talking to students; I don’t work very well if I have only little pieces – I need time to get into something. I try to keep the morning only for science: usually not just for a single problem, usually I’m speaking to four or five people in a morning. If you count everything including writing papers, advising students, then maybe I spend a little more than half of my time on research. The rest is administration, reference letters, committee work, these kind of things.

What do you do for fun?

I sing in a choir, and I also quite like to build and plan stuff. I like to work with wood and build furniture. When I extended my house, I did all the architecture for that. And finally, I still have this astronomy and astrophotography hobby, either at night or during solar eclipses.

david.matthews@timeshighereducation.com

Appointments

Mario Pinto has been appointed deputy vice-chancellor (research) at Griffith University in Australia. He has previously held a number of senior roles at Canadian institutions, including president of the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, and vice-president (research) at Simon Fraser University. Professor Pinto, a chemical biologist, said he joined Griffith because he liked “upstart universities, those who are not fettered by tradition, and willing to engage in bold experiments”, as well as the institution’s “ethos” and its focus on sustainability.

Nic Palmarini has joined the National Innovation Centre for Ageing, based at Newcastle University, as director. Professor Palmarini joins from the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab in Massachusetts, where he was programme manager and the AI ethics lead, and previously served as global manager of AI for healthy ageing. In his new role, he will lead the Newcastle centre’s efforts to research and bring to market products that promote healthy ageing, working across academia and industry. Brian Walker, chair of the Nica board, said that in Professor Palmarini they had “an internationally recognised thought leader in ageing innovation to lead this flagship programme”.

Rathan Subramaniam has been named dean of the University of Otago Medical School. Professor Subramaniam, who will take up the position in February next year, is currently the chief of the division of nuclear medicine at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

Matthew Turk is the new president of the Toyota Technological Institute at Chicago. Previously a professor in the department of computer science at the University of California, Santa Barbara, he succeeds Sadaoki Furui.

Chunlei Liang has been appointed professor of mechanical and aeronautical engineering at Clarkson University. He joins the New York institution from George Washington University.