If you read the personal finance pages of the newspapers, you will be familiar with the truism that investment values go up and down, but losses or gains only become real when you cash them in.

That moment of action crystallises what was, until then, a largely theoretical view of stock markets rising or falling (recently, mostly falling).

A similar rule applies to some debates in higher education, many of which have gone on over such an extended period that it often appears that they will never crystallise one way or the other.

One such question, which has bubbled along for years, is whether the sustained improvement of universities in countries with authoritarian regimes represents a brittle and limited form of success or a genuinely alternative paradigm to that which has served higher education in the West so well.

It is a debate that has been had and had again as universities in China, in particular, soared up the world rankings, but could it be about to crystallise in the wake of the war in Ukraine?

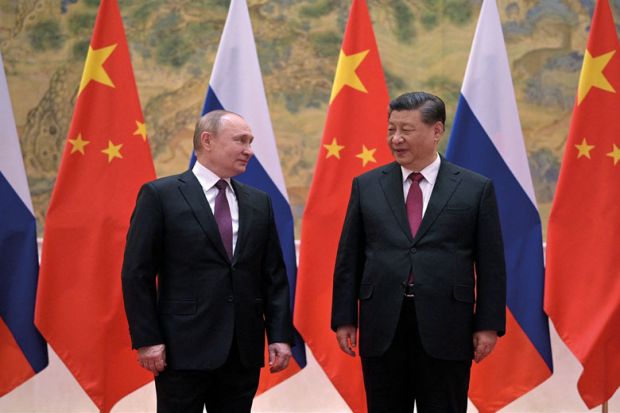

Russia’s attack on its neighbour has aligned the Western allies solidly against the former Soviet superpower, and raised urgent questions of China and what exactly it meant when, just last month, it expressed its commitment to a bilateral partnership with Russia with “no limits”.

In our news pages this week, we take a close look at what some are hailing as the death of globalisation, with world powers splitting into distinct and opposing blocs, would mean for higher education – and whether it is likely to come to pass.

There is some cautious optimism among experts we speak to, who on the whole have not written off globalisation just yet.

But on the question of what a new post-global era would mean for universities and science, the implications are of enormous significance for areas ranging from student flows and academic exchange to the free flow of knowledge and the frameworks used to measure excellence in research.

The questions related to science and research have come under particular scrutiny in the past week, as Russia announced it would stop indexing Russian scientists’ publications in international databases, while numerous sanctions and measures have been imposed by the West.

But another even more fundamental issue at stake is what a new, bipolar approach to higher education would mean for institutional autonomy and academic freedom – which are foundation stones for Western university systems (as evidenced by our features this week on the French university system and the ongoing debates about freedom of speech) but are far from sacrosanct elsewhere.

Thus far, this issue has been most keenly debated in the context of the Chinese system, and it is worth noting how quick UK government minister Chris Philp was to connect Russia and China when speaking at a Times Higher Education event earlier this month.

“I know there is an instinct of openness in higher education,” he said in response to a question on whether UK researchers should continue to work with peers in Russia.

“You want to forget about geopolitics and just collaborate openly, but I think that is not how states like China view higher education and deep research. They view it as a geopolitical tool, and the fact is we need to be cognisant of that and respond appropriately to it.”

The question of autonomy also came crashing into the spotlight at the start of the month when a statement issued by the Russian Union of Rectors put paid to any hope that they might provide some form of internal challenge to Kremlin disinformation and aggression.

“It is very important these days to support our country, our army which defends our security, to support our president who, perhaps, made the most difficult, hard-won but necessary decision in his life,” the rectors said.

This was not a statement issued by university leaders with the freedom and autonomy to seek truth and speak truth to power, and it prompted Nick Hillman, director of the UK’s Higher Education Policy Institute, to observe: “This is the strongest argument I have ever seen for university autonomy.”

It is impossible to know the extent to which such a statement reflects obsequious political obedience, genuinely held sentiment or fear of personal consequences.

But it was another reminder of the divergence under way, and one that has the potential to crystallise in ways that will be even harder to unpick than the motivations of those Russian rectors.