Even though nobody seems quite sure what it means nor how to measure it, value for money has become a defining characteristic of the new model student experience in England. So much so that the Office for Students commissioned its very first research paper on it. The report, Value for money: the student perspective, gives a useful insight into what students think, but deliberately avoids offering a firm definition.

For inspiration, we might look to the Office for National Statistics – which will likely be collating data for the new regulator. The ONS defines value for money as “the optimal use of resources to achieve intended outcomes”. But from a student/consumer perspective, “intended outcomes” brings fresh ambiguity. What might these outcomes be? Landing a highly paid job? Answering 100 per cent in student satisfaction surveys? A life-changing experience gained from deep intellectual enquiry? Or getting the highest degree classification from the cheapest provider? On this last point, the ONS makes it clear that achieving the lowest initial price does not qualify as value for money – which presumably rules out differential fees.

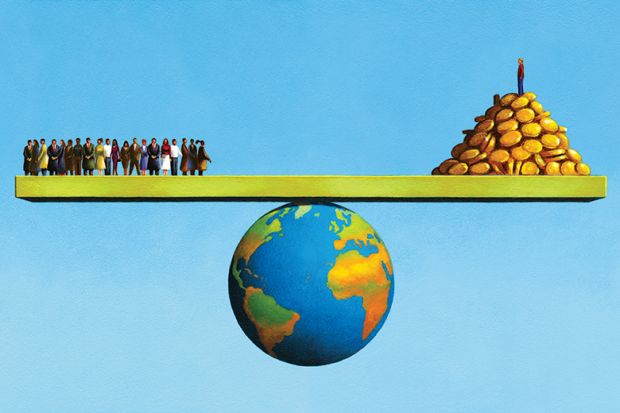

In the context of the raging debate over tuition fees, value for money is pegged exclusively to returns to the individual. But this view is too narrow and risks playing into the hands of critics preoccupied with student “debt”, “rip-off” fees and dumbing down. It’s time we turned the spotlight on the “social value for money” provided by universities to the taxpayer – not only as an antidote to the stagnation or disappearance of public services but also in robust defence of universities under attack from those questioning their relevance.

The idea that publicly funded universities need to reclaim lost ground is not confined to the UK. Having a well-articulated vision around social value for money holds the key to regaining and maintaining trust across our stakeholder base. To that end, the University of Northampton and nine other UK institutions have joined ranks with various social enterprise bodies and the National Union of Students to call on the OfS to explore this concept more explicitly and embed it into the regulatory framework and evaluation of English higher education.

The case is easily made. Put simply, consumption of higher education enriches society in ways that exceed the marginal benefit to the student. Examples include lower unemployment rates, better health outcomes and higher productivity. Whether or not they are graduates themselves, such positive externalities reduce the financial burden on all taxpayers.

Framed in this way, social value for money provides universities with a powerful story linking student demand (input) with provider supply, procurement and social benefits (outcomes). Commentators refer to this relationship somewhat vaguely as public benefit. But to win over an increasingly sceptical audience, we must be more persuasive and analytical in our arguments. And that means starting at home.

Yet here lies a problem. The public frameworks tracking the outputs of universities are largely silent on social value as a metric of success. Take, for example, the teaching excellence framework’s emphasis on individual satisfaction and earning potential, arguably at the expense of any wider benefit to society. Clearly, the TEF needs institutional focus to have any credibility. But a misplaced fixation on graduate salaries as a proxy for value for money risks penalising institutions training students for public sector jobs that provide the most immediate positive externality from higher education.

The research excellence framework assesses “impact”. But imagine how much more powerful a driver of behaviour it would be if departments were assessed and rewarded – even in part – on their ability to harness social and community assets derived from publicly funded research, for the common good. For instance, a university gym could be opened to the public on the proviso that users participated in sports science research.

As for the knowledge exchange framework, I have no idea if it will ever get off the ground. If it does, a ranking based predominantly on technological innovation in the form of patents, disclosures and intellectual property income would be a lost opportunity and do little to accelerate the social impact of universities.

There is tremendous untapped potential for universities to do more to build social infrastructure through replication of best practice, should the regulatory system choose to enable it. Many universities have an offer comparable with some of the UK’s best social enterprise start-up support agencies and programmes. The sector, however, needs to make the case more persuasively to leverage investment.

The OfS has a golden opportunity to show leadership by promoting social value over the individual value-for-money benefit our students expect – and receive. Yes, the student interest must be protected. But the institutional interest must be protected, too, where there is a clear and vital overlap. Social value for money provides an overarching, ambitious narrative for the new regulator to champion.

Nick Petford is vice-chancellor of the University of Northampton.

后记

Print headline: Real value for money benefits everyone, not just individuals