In his farewell speech as he retired from the House of Lords last month, the Oscar-winning film-maker David Puttnam offered an excoriating review of political and public debate.

“I can’t be the only member who’s become increasingly frustrated by the fact that in Parliament, as elsewhere, we no longer engage in serious ‘debate’ – we simply trade assertions,” he said.

“‘Debate’, as I have always understood it, is ‘persuasion’ based on competing interpretations of evidence and the ability to form a compelling argument and, where necessary, seek compromise.

“Sadly, that’s been substituted by a ‘dialogue of the deaf, typified by the government’s refusal to answer serious questions or offer any well-thought-through arguments in defence of seemingly immutable positions. Their view appears to be: ‘We are the government – take it or leave it!’”

This warning about the backwards slide of one of the cornerstones of democracy – open, sometimes fractious, always essential debate about matters of public importance – was well made.

The debacle of last week’s whipped House of Commons vote to scrap inconvenient parliamentary standards processes illustrated the point with painful clarity, an injury not much remedied by the subsequent U-turn.

But, as Lord Puttnam noted with that all-important “as elsewhere”, this conflation or outright replacement of persuasion with assertion is not in any way unique to politics.

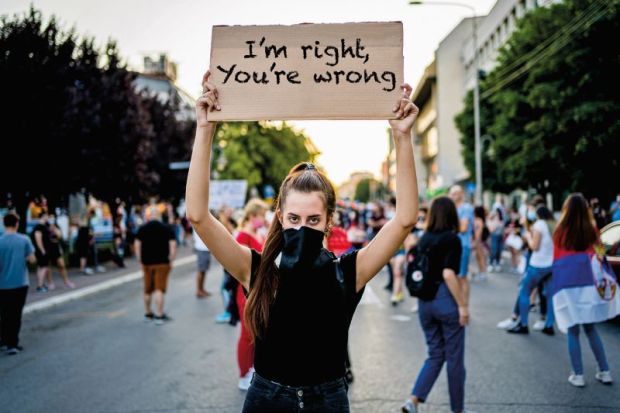

Social media has fuelled a population-wide shift in this direction, rewarding with vacuous yet oh-so-self-affirming likes and retweets those who plant flags and denounce all who disagree.

Universities, with their founding principles of the pursuit of truth, evidence and reason, are naturally expected to be among the strongest bulwarks protecting us from this dangerous drift.

They exist to open minds, to foster critical thinking and to imbue respect for freedom of enquiry and expression.

As Adam Tickell, vice-chancellor of the University of Sussex, said in response to the recent campaign to drive philosopher Kathleen Stock out of her job because of her views on gender identity, academics must have “an untrammelled right to say and believe what they think”.

He was both right and brave to say so, though it is extraordinary that this should be the case.

It is easy to assert that academic freedom must mean what it says on the tin, but how can that be enacted when fee-paying students campaign relentlessly on an issue, and even the lecturers’ union washes its hands of a one-time member, as happened in Stock’s case?

While it would not be true to say that this issue has crept up, it feels as though it has escalated considerably.

Rewind a few years to 2018, and Tickell told a parliamentary committee that anxiety about supposed threats to free speech on campus was being “whipped up to create a moral panic”.

His point – that isolated cases did not constitute a crisis – was a fair one at the time, but today this seems like an increasingly untenable position for universities to adopt, when the ramifications of those cases and the reputational damage are so significant.

Whether freedom of speech is an issue that therefore requires legislative intervention is another matter; most would say emphatically not, since it is highly unlikely that any such law would effectively deal with the issues at play, and the autonomy of universities is a vital underpinning of their crucial role as a bulwark of independent thought.

But the best way to avoid such intervention is to step up, to be brave and to find ways to resolve the issue – not to ignore or refute it.

In our features pages, we interview Ron Daniels, president of Johns Hopkins University and an outspoken advocate for universities’ role in defending democracy, who argues that while “the characterisation of universities as monocultures, and hugely susceptible to the chilling effect of cancel culture, is overstated”, it would be wrong to deny that there was a problem.

He identifies a generational challenge, arguing that students entering university now “come in with less faith in how that contestation, that open, vigorous debate, makes everyone better off”.

In some ways it is an old story: new generations testing, contesting and tearing things down. But in the past, that was a process largely facilitated by that ideal of open debate and challenge embodied by the university.

The difference this time is that it is precisely that dispassionate commitment to robust debate that is under threat.