It had been a long afternoon. The examiners had deemed the international student’s thesis weak, but had hoped she would redeem herself in the viva. But they had been disappointed. She was pleasant and keen but was nowhere near the level expected for a PhD.

They asked the student to leave the room while they discussed her case. The conversation touched on many points – to what extent was the supervisor at fault; was this someone who should never have been taken on; did she not have enough background knowledge? But after circling around the issue for 10 minutes, they could no longer avoid making the decision to fail her.

So the discussion then continued: should she be allowed to resubmit? Slowly, painfully, the examiners agreed that they needed to be cruel to be kind. This student would never get a PhD – at least, not on this project – and had just about reached the level for an MPhil. That is what they would recommend.

They called the student in. She clearly knew that she had not done well, and was on the verge of tears. What they were not prepared for was the horror and total devastation when they delivered their verdict. “You cannot do this to me, to my family,” she shouted angrily. “It will destroy them.”

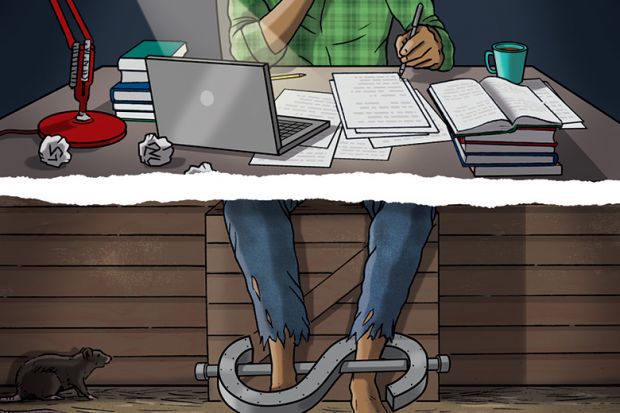

The supervisor, who was pacing the corridor outside, was called in. It slowly emerged that the student’s fees and living costs were paid by her home country. In return, she was bonded to work for four years after her studies in a university back home. However, if she failed she would have to repay her costs with interest. Her parents had acted as sureties, so they were in danger of losing both their home and their good name, as she would be shamed in the local newspaper as a failure.

The supervisor had been vaguely aware that the scholarship bonded the student to work in her home country, but had known nothing of the consequences of failure. The examiners felt that all this put them in a very difficult position, and agonised over whether to reconsider their decision.

This is a fictional account – but one based on elements of vivas (fortunately few) that I have been involved in over the years as an examiner, supervisor and director of a graduate school. Many overseas students are bonded to work for their funding bodies when they finish their studies, especially following doctorates. Most academics probably see this as a private matter between the student and their funder. It has the virtue of ensuring that developing countries can retain talent they invest so heavily in, while many potential students would see the benefit of guaranteed postdoctoral employment. There is little difference between such arrangements and scholarships or bursaries from companies or the military that require students to work or serve post-graduation.

But while I am not aware of any cases in which students have been passed because the examiners are worried about the consequences of failure, situations like the one described above certainly put unfair pressure on examiners and supervisors, and so could endanger standards.

Universities and supervisors need to mitigate the risks of bonding. To do that, we should only accept those students with a good chance of succeeding, monitor them carefully to give early warning of problems, and terminate their registration when it is apparent that things are not working out – before they rack up too much potential debt to their funders.

Supervisors can be tempted, when there is a productive student and the work is going well, to request an extension so that better publications come from the work. However, the consequences of any extension for bonding agreements should also be taken into account.

Western institutions also need to talk about bonding arrangements when setting up partnerships with funders in other countries (or, indeed, with domestic businesses). One such arrangement I was involved in initially had a clause that required the repayment of fees and living costs if the student failed their PhD. Following discussion, the funder agreed that, instead, failed students would still be bonded to work in their organisation, but not at a doctoral level, and would not be financially penalised.

Appropriate selection and careful monitoring is good practice regarding all students, and most universities recognise that. But the consequences of bonding heighten the responsibility of both the supervisor and the establishment to ensure that such practices are being adopted at ground level.

Are any of your students bonded after their studies? Do you know how long for, and what the regulations are? If not, don’t you think that you should?

Andrew George is deputy vice-chancellor (education and international) at Brunel University London.