Happiness is a cigar called Hamlet. Or a warm gun. Or, perhaps, being young.

Except it isn’t. The first two are obviously nonsense – cigars are foul, and so are guns.

But it’s increasingly hard to make a case for the third, too.

The current generation of young people – let’s say 18-30-year-olds for want of a better definition – has been dealt a tough hand in all sorts of respects.

Even if we restrict ourselves to those living in England, and to primarily financial concerns, the list of challenges is long.

Chances of owning your own home? Slim in large swathes of the country and slimmer still in the South East, where most of the well-paid jobs are (unless your parents can help you out).

Sense that the country has your interests at heart? Not really, for the majority who voted to remain in the European Union and saw older voters decide on a different future for them.

Prospects of a secure, rewarding career with a comfortable retirement and decent pension on the other side? Hmm.

A life-enhancing time at university with a focus on learning for its own sake, free from crushing parental expectations and self-imposed anguish over the £50,000 loan debt they’ll graduate with? Eek!

Despite the solid logic of the income-contingent loans system, and the lack of a credible alternative to maintain both the unprecedented level of access to higher education and the unit of resource, keeping calm and ignoring the furore over student debt looks like a political busted flush.

Which is why Theresa May this week announced alterations – and they are just tweaks – to the fee cap (now frozen at £9,250) and repayment threshold (lifted to £25,000).

Whether these changes, which by May’s reckoning will put an extra £30 in graduates’ pockets each month, do enough to head off the fees frenzy seems unlikely.

In apparent recognition of this, May used her closing speech at the Conservative Party Conference on 4 November to announce a “major review” of higher education funding.

The Conservatives have clearly been forced into this review, for reasons touched on by David Willetts, the former universities minister who now heads the Resolution Foundation thinktank, who highlighted last week that the lifestyles of the young are falling ever further behind those of their parents and grandparents.

This is the context in which tuition fees have become a lightning rod through which much larger – and even harder to fix – disparities are being channelled.

Few of the wider indignities and inequalities visited on the young look likely to be redressed any time soon – Brexit or house prices, anyone?

Which means that regardless of the risks of forcing through reforms to create price competition between universities, for example, or widespread two-year degrees, or even renewed number controls, none are beyond question.

The last of these would be a particular blow for the young, 49 per cent of whom now benefit from higher education.

Indeed, Nick Hillman, director of the Higher Education Policy Institute, argues that if anything, the participation target should be increased, to 70 per cent (although not necessarily delivered in the same old ways).

This backdrop also makes it more pressing that higher education leaders act whenever possible to draw poison from other festering sores – yes, including excessively high pay.

The fact that a few pay cuts at the top will do next to nothing to make higher education more affordable is no longer the point, if it ever was.

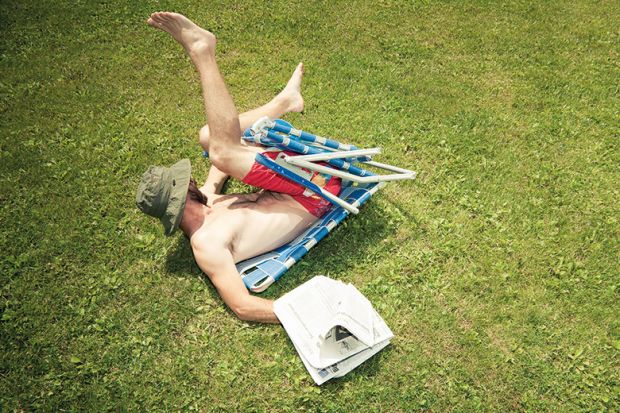

If this all seems a bit gloomy, then why not turn read our lead feature for some ideas about how to cheer yourself up.

We asked scholars in fields ranging from economics to psychology to neuroscience how to be happy, so there’s something for everyone.

Even, dare I say it, vice-chancellors considering a modest pay cut – for as Andrew Oswald, professor of economics and behavioural science at the University of Warwick, points out, money doesn’t really make us happy anyway. Or it does, but only up to a point.

And if taking home just a couple of hundred thousand feels like a hard bargain, look on the bright side – you could be 21 again. That really is a tough gig.