After years of wall-to-wall Brexit coverage, it was a little strange that in the week that Britain formally left the European Union, it was China that dominated the news headlines.

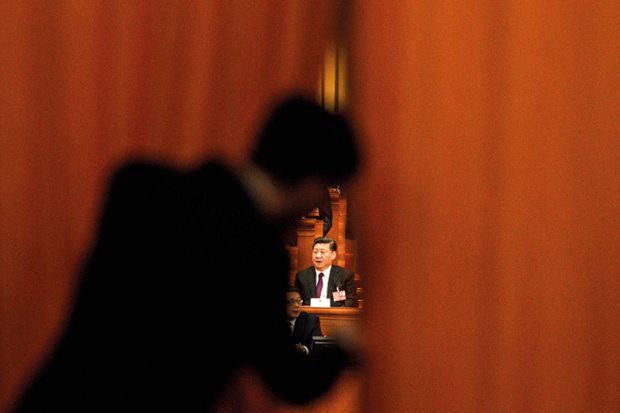

The heat of battle has left the Brexit debate, but it’s more a reflection of the enormous influence China now wields in world affairs. Among the numerous stories touching on the geopolitical tension were Britain’s decision to grant the Chinese telecoms firm Huawei a role in building its 5G network, the global spotlight on China’s efforts to contain the deadly coronavirus, and, in higher education, an extraordinary tale from the US, where a Harvard professor was arrested and charged over alleged secret contractual ties to a Chinese government programme.

Against this backdrop, discussions at a seminar in Westminster organised by the Higher Education Policy Institute and AdvanceHE took a timely look at how universities in Western countries are conducting their collaboration with China (a topic we also examine in our cover story).

Simon Marginson, professor of higher education at the University of Oxford, told the seminar that “the US-China stand-off is unsurprising – China could not keep rising forever without pushback”.

What’s more, “the US breakdown with China may create openings for UK institutions, but we need to understand…[that] this culture is as complex as our own and is very, very different”.

These differences underpin many of the tensions that universities in the West are now contending with, particularly as more populist and protectionist policies take root at home.

Speaking at the same seminar in London, Vikki Thomson, chief executive of the Australian Group of Eight (which represents the country’s research-intensive universities), described how her organisation had sought to head off government interference in international collaborations and networks.

Rather than allow an information gap to persist between universities and national security agencies, the sector had worked with them to develop a set of guidelines laying out agreed ways of working. She likened this approach to accepting “tall fences around small areas” as preferable to the alternatives.

Whereas before, agencies would “tell us there’s an unprecedented level of foreign espionage…but [say] we can’t tell you what it is”, now there is a clearer dialogue and “an appreciation and understanding of [universities’] value to the economy…and that we must protect this”, she said.

During questions held under Chatham House Rules, one delegate raised concerns that universities should be doing any sort of deal with security agencies over matters of research collaboration.

However, others took a more pragmatic view. One said that the US view of Britain was that “we are naive about what they call ‘dual use research of concern’ – a long list of areas that we would consider innocent civil research, but which they think have other uses”.

While Britain has “a very explicit and clear set of export control rules for business, we don’t have any for research. There is now a need for some sort of guidance for researchers about what the sensitive technologies are, what we can share, and on what basis,” they argued.

With Britain’s research base facing a future that may or may not allow continued access to EU funds, concern was also voiced about the “nightmare scenario” of the UK failing to secure full association to Horizon Europe, but also losing funding allocated for research with rising powers.

While EU funding programmes have been crucial to the strength of UK research in recent decades, it has been further bolstered by UK funding allocated for Official Development Assistance, it was pointed out.

“We have successfully grown research funding under ODA. But quite a lot of middle-income countries, including China, cease to be ODA at some point in the middle of this decade. So the sector needs to think strategically: what is it we need to design for this scenario?”

Britain is only a week into its post-Brexit life, and the transition arrangements provide some immediate breathing space – although not a lot.

As Marginson put it at last week’s discussion, whether or not there is a new world order can be debated, but there’s no arguing that as of 1 February “the UK has reordered itself”.

If that opens a window of opportunity to reshape the country’s place in the world, with universities and research to the fore, “that window will not stay open for long”.