The latest release of Australian university financial data by the Department of Education and Training in January further undermines the government’s case that universities can sustain significant reductions in revenue from public sources.

The government’s false assertions about the financial robustness of universities and over-egged claims about the increase in public funding for universities over the past decade underpinned its case in 2017 for a major funding cut, in part offset by higher student charges. When it failed to get that proposal through the Senate, it announced that it would freeze funding at 2017 levels for 2018 and 2019.

The latest figures, for 2016, show that universities that planned to keep growing under demand-driven funding simply won’t have enough money to do so beyond 2018. The political question is therefore whether the government can sustain its position into the 2019 election, allowing it to alter the legal basis of university funding from uncapped place numbers to a ministerially driven funding amount. If Labor wins the election, universities will expect it to lift the freeze.

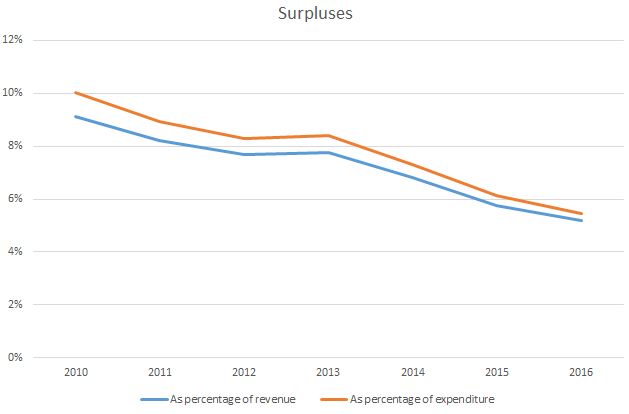

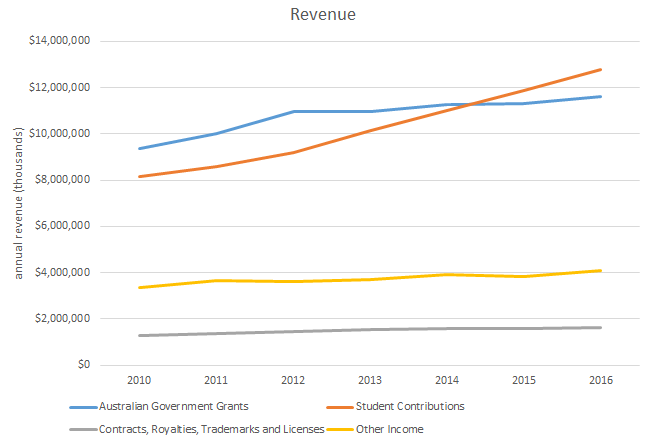

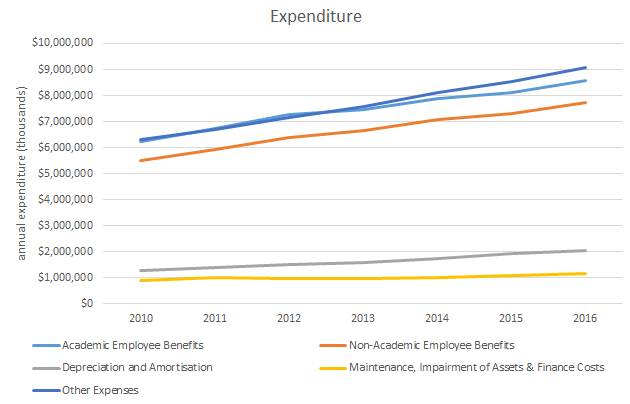

Between 2010 and 2016, revenue for all universities rose by 36 per cent, but expenditure increased by 42 per cent. The inevitable consequence is that the healthy university surpluses of several years ago have shrunk to barely sustainable levels. From 2010 to 2016, the surplus has halved, from 9 per cent of revenue to 5 per cent.

The outcome is more extreme for members of the Innovative Research Universities (IRU) group that I lead. These second-generation research universities, which target excellent outcomes for a broad range of students, had an upsurge in their annual surpluses from 2009 to 2012, associated with the initial expansion in domestic places leading into the demand-driven system and the additional capital grants provided by the Labor government’s economic stimulus measures. But, overall, IRU institutions saw a 43 per cent increase in their expenditure between 2010 and 2016, against a revenue increase of 30 per cent, resulting in their surpluses falling from 13 per cent of revenue to 4 per cent: a level that will barely support investment in future sustainability.

There are also interesting changes in the mix of revenue and expenditure. Australian universities have achieved significant structural change in how they use revenue, tightly constraining recurrent costs, notably staffing. Between 2010 and 2016, revenue from students rose much more (57 per cent) than revenue from the government (24 per cent). This means that, by 2015, Australian universities were receiving more from students than from all government sources, including research funding.

Both academic and professional staff benefits have risen steadily, with the former still about 11 per cent higher than the latter. But what stands out most is that expenditure on depreciation and amortisation (principally, the cost of loan repayments) has risen particularly sharply as universities have taken on the responsibility of funding the maintenance and renewal of facilities.

All Australian universities expanded their student numbers in the demand-driven era, requiring considerable renewal of teaching facilities to meet student needs. University property plant and equipment was valued at A$46 billion (£26 billion) in 2016, but there is no ongoing source of capital funding to support institutions’ continuing efforts to make their facilities fit for the educational future, such as making buildings digitally capable.

The government’s previous Capital Development Pool ceased at the end of 2011. And while the Education Investment Fund, introduced in 2008-09 with the aim of producing a “modern, productive, internationally competitive Australian economy”, provided large amounts of funding, this was targeted at high-profile new buildings. This reduced pressure by removing competition for scare funds for big new facilities, such as research centres, but it did not help with the renewal of existing campus facilities. Moreover, the fund was closed at the end of 2014 on the recommendation of the Abbott government’s National Commission of Audit.

So while Australian universities have had a good decade expanding numbers to ensure the country’s citizens are ready for the employment options of the 2020s, their ability to continue doing so is open to question if the government insists on reducing its investment.

Conor King is executive director of the Innovative Research Universities mission group.