Ron Dore, who died in November, would have found 2019’s early higher education headlines entirely and sadly predictable. They include ever-rising enrolment around the world irrespective of economic growth rates; fierce international competition for the millions of students pursuing overseas degrees; soaring numbers of unconditional offers and first-class degrees in England; and student debt crises in the US and India alike. All are manifestations of what the celebrated British polymath labelled “the diploma disease”.

Dore’s 1976 book of that name richly repays a second, or first, read. This disease, as he was at pains to emphasise, “is something that societies, not individuals, get”, and is a direct outgrowth of certain positive aspects of modernity: governments committed to economic development, and a belief that objective criteria, not family connections, should form the basis for hiring and promotion. Yet, as analysts around the world learned from him, the results all too often waste resources and degrade education itself.

Born in 1925 to working-class parents, Dore himself needed only a grammar school education and an undergraduate degree (obtained as an external student of the University of London) to launch an academic career. During that career, he contributed across the social sciences: anthropology, social history, sociology, development studies, education, management, political science, cultural studies and economics, as well as Japanese studies.

Dore learned Japanese on a wartime course. He became a fluent speaker and writer, even able to read pre-modern archive documents in the original, and his early research was on education in Tokugawa Japan (1603-1868), city life in Japan in the 1950s and land reform in post-war Japan. Education in Tokugawa Japan, published in 1965, became a classic text.

Dore worked at several universities in the UK and North America and wrote about modernisation, capitalism, industrialisation, vocational training, internationalism and income inequality. During a distinguished period at the University of Sussex, he led a research programme on qualifications and selection in education systems in China, Sri Lanka, Ghana, Mexico and Malaysia. He was in Sri Lanka with the International Labour Organisation during the 1971 “youth insurgency”, amid the large-scale unemployment among educated young people caused by rapid expansion of the school system at a time of slow economic growth. This experience, as well as that of Japan, was central to The Diploma Disease, which was revised in the rather different world of 1997.

Dore argued that, other things being equal, the later that government-driven modernisation starts, the more widely education certificates are used for occupational selection, the faster the rate of qualification inflation and the more examination-oriented schooling becomes, at the expense of “genuine” education” – which, for Dore, was one that nurtured curiosity, problem-solving and imagination.

There is some strong evidence for Dore’s theory, although, as is common in social development scholarship, the world is not as neat and tidy as the hypothesis suggests. University enrolment rates are certainly far higher, for a given level of income per head, in today’s developing countries than they were in Western nations at comparable income levels. But the “bureaucratisation” of the labour market, with its insistence on formal procedures, fuels the pursuit of certificates in developed countries as much as in developing countries. And while widespread graduate unemployment may not be a first-world phenomenon, overqualification certainly is.

In his foreword to his revised edition, Dore did note that manifestations of the diploma disease were increasingly present in the UK despite its early start on the road to development. “The spiral of qualification is moving faster,” he observed, as growth in student numbers outpaced changes in the occupational structure. The results are obvious in the current evidence on wage returns to degrees, which are falling on average and widening in variability.

The Japan of the 1960s had a very finely graded hierarchy of universities, and students’ future jobs depended enormously on which one they attended. This, Dore argued, had been far less true in the UK during the same period. But, by 1997, he saw this difference fading. Today, with participation rates approaching 50 per cent, the UK’s university hierarchy is supported by government commitment to ever more formal metrics; it matters more and more which university a graduate attended.

Dore emphasised that these unintended consequences came about because of rational behaviour by individuals. He also, at times, believed that socialist governments, such as those of China, Cuba or Tanzania of the 1970s, might have bucked the trend. But so far, there is little evidence for that.

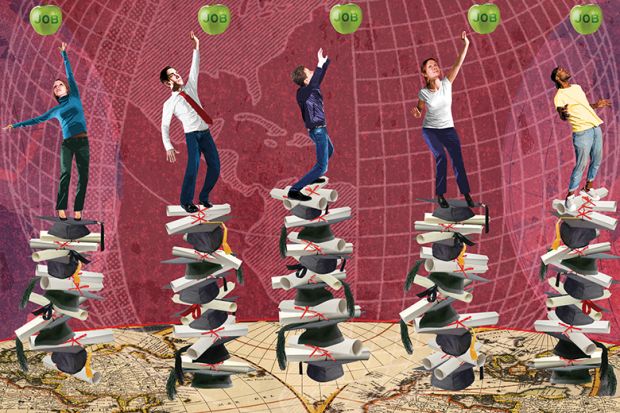

Instead, Dore’s thesis is now being played out on an ever-larger scale. Employers are moving jobs around the world, and young people are chasing them with ever more qualifications. The international assessment business is thriving, with university league tables steering the choices of students who can afford to pay fees in their country of choice. All are symptoms of a globalised form of Dore’s diploma disease.

Keith M. Lewin is professor emeritus, international development and education, at the University of Sussex; Angela W. Little is professor emerita, education and international development, at UCL Institute of Education; and Baroness Wolf of Dulwich is Sir Roy Griffiths professor of public sector management at King’s College London.

后记

Print headline: The fever spreads as the diploma disease becomes a pandemic