Those who use the Tube in London will be familiar with the passenger information boards offering up cod philosophy and thoughts for the day.

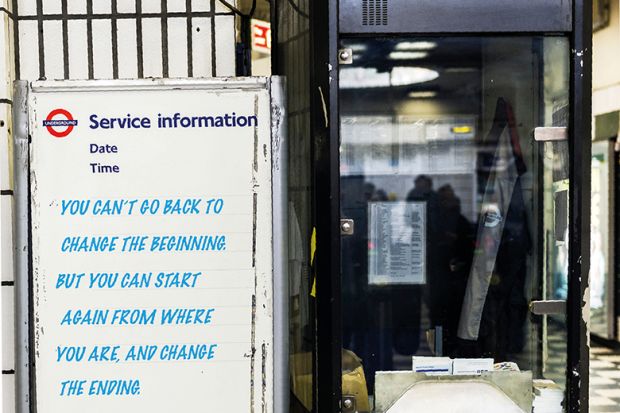

At Knightsbridge station the other day, I noticed a steady stream of people stopping to photograph the whiteboard standing by the ticket barriers. It offered the following homespun wisdom: “You can’t go back to change the beginning. But you can start again from where you are, and change the ending.” Feeling inspired? Well, perhaps you are less of a cynic than I am.

The words floated back into my head, however, as I leafed through this week’s news and features, which repeatedly touch on that most fraught of questions in higher education: the extent to which universities can and do transform lives, rather than just perpetuate privilege.

It is a topic that is addressed explicitly in our cover story, in which we ask eight contributors to give us one big idea for improving higher education.

Among them is Douglas McWilliams, author of a new book, The Inequality Paradox, who argues that despite the policy emphasis and funding thrown at widening participation, “the scale of the ambition and the extent of the progress can be questioned”.

His analysis is that with existing, well-intentioned efforts failing to address educational inequality, it may be time for a radical rethink of university funding, with much clearer incentives.

Similarly, in our news pages, we cover a major new study of policies globally in which Jamil Salmi, a tertiary education expert formerly of the World Bank, concludes that too many countries pay only “lip service” to widening participation.

In our second feature, meanwhile, we offer a scholar’s assessment of the contested concept of IQ and its suitability for use in university admissions.

The analysis by Kenneth Richardson, an expert on human development, explores a wide range of research and concludes that IQ tests are, in the end, “just tests of certain kinds of learned knowledge, along with self-confidence”. As such, he argues, “you could also depict them as measures of social class background”.

This is most clearly illustrated, Richardson suggests, by the dramatic rise in average IQ scores during periods of economic development and consequent upward social mobility – as measured by the growth of middle-class jobs – and the levelling-off when such development slows.

His conclusion is that IQ is no better (and quite possibly worse) than many other modes of assessment, either at predicting success at university and beyond, or at isolating an individual’s successes from their family’s social and economic situation.

This issue of educational inequality and what to do about it has also been brought to the fore by the donation of $1.8 billion (£1.4 billion) to Johns Hopkins University by the businessman Michael Bloomberg.

This is an exceptional donation in a number of ways – the largest ever to a US university, and targeted entirely at helping to guarantee needs-blind admission.

As we report, Bloomberg – who is considered to be a future challenger of Donald Trump – sees financial barriers to college inflicting harm on the country by perpetuating intergenerational poverty.

But inevitably his generosity has sparked debate about how helpful even such a huge sum of money is in tackling this inequality when it focuses on one elite institution (which has ambitions to increase the proportion of Pell Grant eligibility among its students from 15 per cent to 20 per cent).

An estimated 45 million Americans owe a total of $1.5 trillion in student loans – so even Bloomberg’s $1.8 billion gift would give each of them only a $40 break.

Nor can any donation compensate for the huge disadvantages that many young people have already faced, which render university admission an expensive triumph for some and a mere formality for others.

The universities that attempt to compensate for this by making lower offers to more disadvantaged students are often castigated; the current legal tussle over the role of race in Harvard University’s admissions policy is a case in point.

In the UK, universities using contextual admissions are often dismissed as “social engineers”. But, ultimately, exactly what is the difference between social mobility (good) and social engineering (bad)? And can the former be achieved at scale without the latter playing a part?

If universities really are in the business of “changing the ending”, rather than just entrenching existing advantage, they must surely take a long, hard look at what that actually requires them to do in the socio-economic context in which they operate.

后记

Print headline: Level best could be better